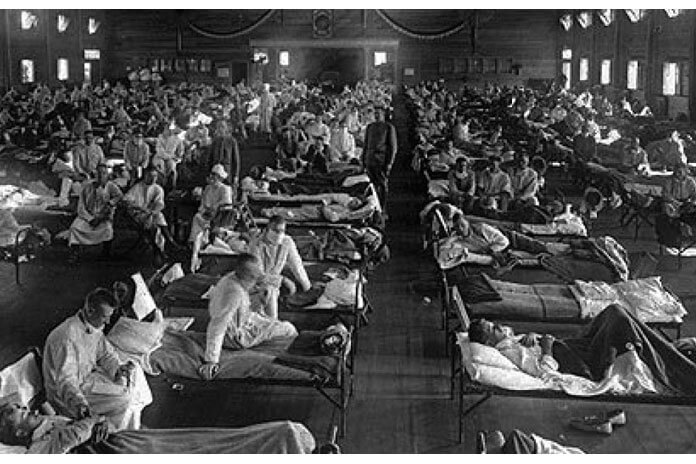

6 June 2020– “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…” wrote Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities amidst the disquietude preceding the French Revolution. Belize, like the rest of the world, is experiencing a “worst of times,” which, if we see it in the context of traversing through a tunnel rather than falling into a pit, could end up being the “best of times”. Professors Grant D. Jones and Joel Wainwright in “The 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic in Corozal, Belize: An Unclaimed Letter Rediscovered” published in the Amandala on April 24, 2020, speak about historical reflection as a “tonic” against disquietude in this worst of times.

Sr. Barbara A. Flores, SCN, Belizean educator and theologian, at the 12th Annual Signa York Memorial Lecture, takes historical reflection a step further when she speaks of soul-searching as a way of undoing the colonizer in us1. In this regard, she prompts us to introspection as a way of healing our historical memory. After all, as Jesuit Matt Malone says, memory is the soul of conscience, which is the motive force of change2. The current state of affairs, then, is opportune for soul-searching.

With the scant documention on the Belizean experience of the 1918 Influenza pandemic commonly known as the Spanish Flu, documents of the day such as the Hassock letter presented by Jones and Wainwright, hold significant historical value and draw on the human need for reaching out, as the authors are prompt to say, in the worst of times. The Arturo Versavel letter attests to another expression of human empathy, that of solidarity.

Fr. Arturo Versavel, a Jesuit priest who served as pastor in Benque Viejo del Carmen from 1908– 23, is credited for having brought down the Pallottine Missionary Sisters to serve in the elementary school system in Belize in 1913. In the early 1990’s, I had the opportunity to access the church records at the Jesuit Residence in Belize City3. It was among the pages of the house diaries of Benqueviejensis Residentia that I came across Fr. Versavel’s letter reporting on the 1918 pandemic.

The Influenza is said to have been introduced on October 11, 1918 into Belize Town by workers of the United Fruit Company arriving by boat from Puerto Barrios, with the last reported case happening on December 10, 19184. During this time, 100 deaths were recorded for Belize Town, putting the mortality rate in the old capital at 4%5. With an estimated population of 42,368 in British Honduras6, the overall mortality rate was 5.9%7. The first case of Influenza at El Cayo (San Ignacio) was reported on October 24, 1918, and, according to the report by Acting Medical Officer George H. Lewis, it was imported from Belize Town via the passenger boat Cacique”8. In his report, Lewis writes, “Unfortunately, I was one of the first victims and by November 7th, when I was able to return to my medical duties, found that practically the whole town was affected”9. It should be noted that El Cayo, just like Benque Viejo del Carmen, had approximately one thousand inhabitants. AMO Lewis stresses upon the generosity of Cayo residents who assisted the unfortunate with money, food, and service. Lewis estimates the number of infections at about 2,000 for the Cayo District. The death toll was recorded as 136, with 33 for the village of San José Succotz which, like many of the Maya communities across the colony, had a high rate of morbidity10. Lewis concludes his report by listing the deficiencies of the times, namely, the lack of health care personnel, inadequate transportation, and a flawed system of communication via a telephone line which was down for the most part.

The information provided in Fr. Versavel’s letter differs from the figures given by the AMO. Fr. Versavel puts the death toll for Succotz at 70, out of a population of 310, and for Benque Viejo, 33 out of its 1,000 inhabitants11. The letter, styled in elegant penmanship on ordinary bond paper, is dated December 22, 1919 and addressed to Fr. Henneman. It reads:

[…] As I recollect, the pest struck us toward the end of October. It developed rapidly especially in Succotz. Our hardest time was in mid-November when at one time we had between Succotz and Benque from 7 to 800 people stricken at the same time. 70 people out of 310 total population died in Succotz and 33 in Benque. Of course, we were busy day and night. One day, I counted my calls in Succotz, attending individually 123 people either materially or spiritually. Relief Committee did good work but I was too busy to do much of that work, only referring desititute cases to them. Relief was always given. The Sisters did excellent work. I generally divided the work with them by visiting the northern part of the town in the morning while they took the southern. In this they would refer to me all urgent cases at noon when I also informed them of the names of those who most required their help.

Sr. Dominica caught the plague and was for several days in great danger. Sr. Reinildis had a slight attack; I had nothing but tired legs and bones everyday and the sad pity of burying my people. School was opened in the second week in December with very little attendance however. The pest lingered about us till February.

Signed

Arturo Versavel”12

It is evident that volunteer service played a crucial role throughout the 1918 pandemic, as Versavel readily points out when alluding to the work of the relief committee and the Pallottine sisters in Benque Viejo. As a matter of fact, the compassionate care by German nuns who had arrived five years earlier may have prompted Versavel to put as postscript to the story:

“I may add that the doctor stated that the lower mortality of Benque Viejo, in comparison with that of El Cayo, was owing to the nursing of the Sisters, both towns having about 1000 souls each.”

As in many of the communities throughout Belize, the dead in Benque Viejo were buried in common graves at the campo santo – the municipal burial ground, what is today Centennial Memorial Park. Three names that stand out in the Benque Viejo narrative are those of Leopoldo Mendez, Gabino Quetzal, and Elias Contreras, who offered to bury the bodies 6 feet underground, wrapped in burlap sacks.

I still preserve the annotations on Gabino Quetzal’s experience during the 1918 influenza, which he shared before his death. My recollection of Quetzal is that of a venerable elder kneeling at the verandah of the old Mena’s house in Benque Viejo on a sunny afternoon on July 16 while the procession of Our Lady of Mount Carmel went by. This draws me to reflect on the fact that if we are to seek the light at the other end of the tunnel, we must do so in humbleness by virtue of our fragility against the monumental indifference of nature — as German filmmaker Werner Herzog puts it, and become present to one another as a community, in much the same way our predecessors did a hundred years ago.

The current episode in our story urges us to come to grips with our memory as a nation, in line with what Sr. Barbara Flores outlines. This calls for a shift in our cultural paradigms, a transformation in living out to the fullest the best of times. It is imperative for us, then, as Flores denotes, to celebrate our stories, while rejoicing in our core cultural values and traditions as a multi-faceted nation, knowing that God, as well as those who have preceeded us in time and space, are walking with us in our mission to shape the Belizean homeland.

Raniero Cantalamessa, OFM, Cap., in his reflection on the current pandemic, underscores the heroism laid manifest in the spirit of community displayed in cities, towns, and villages throughout this pandemic13. Failing to see its value through the optics of the best of times would be tantamount to remaining in lockdown to an old norm in the worst of times. It is this kind of recession, Catalamessa points out, that we ought to dread. In this regard, introspection as an inward journey becomes a blessing in every way, for in the act of freeing ourselves, we come to an encounter with our own true self to become a gift for others. Thus, in this inward journey to self, we are able to harness the power to embrace newness in the re-creation of social and economic structures that are humanistic, inclusive, and equitable.

The Spanish Flu lingered on until the summer of 1919, taking its toll on a third of the world’s population. The so called ‘herd’ immunity may have been achieved then14. In British Honduras, churches, schools, and entertainment places were closed, with gatherings reduced to 10 persons or less, and people were advised to use a handkerchief dampened with eucalyptus oil to cover their mouth and nose. According to PMO Gann, quarantine lessened the spread of the disease, which in the end, recorded some 1,014 deaths out of 17,256 reported cases of infection15.

There is every indication that COVID-19 will be walking with us for a while. Belize is far from acquiring ‘herd’ immunity, and a vaccine is not forthcoming. As such, the moment is ‘kairos’ for us to reclaim our story in order to unleash our human potential as a nation.

The story brought to life through modest writings like the Hassock and Versavel letters pours upon us a spirit of resilience and heroism of the few who did so much for so many, echoing Winston Churchill’s wartime speech. Actualizing these stories is an invaluable tool in making a conscious decision to seek the light beyond the tunnel so that as a re-created nation we may reclaim our stature as the new Belizean citizens —those men and women who, in the vision of George Cadle Price, will “[bring] earth nearer to heaven, perfecting creation, from which will arise the new world of time and eternity1616.”

__________________________________________________

1

Flores, Barbara A. “Culture, Spirituality and Transformation: Undoing the Colonizer Within Us. “ Belizean Studies 24.2 (2002): 1-7. Print.

2

Malone, Matt. “An open letter to my fellow white Americans.” 8 June 2020.

America: The Jesuit Review.

Web 8 June 2020. < https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society>.

3

The archives for Belize is now under the care of the Jesuit Archives & Resource Center, which holds the memories of 14 past and current administrative provinces in the United States, including the Missouri Province to which the Jesuit Belize Mission has been attached since 1894.

4 Gann, Thomas. Report on the recent epidemic of influenza. 17 December 1918. Minute Paper 3527-18. Accessed at “The 1918 Spanish Influenza in British Honduras.” Ambergris Caye. Com. 1 April 2020. Web. 3 June 2020. <http:// ambergriscaye.com/forum/ubbthreads.php/topics/541420/the-1918-spanish-influenza-in-british-honduras>.

5

ibid.

6 Keltie, John Scott, and M. Epstein, ed. The Statesman’s Year Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the year 1920.

London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1920. 3 June 2020. Web. <https://books.google.com.bz>.

7

It is estimated that a third of the world

’s population – 500 million, got infected with a mortality rate of 10%. “1918 Pandemic (H1N1 Virus).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 20 March 2019. Web. 3 June 2020. <http://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html>.

8

Report dated January 12, 1919 to PMO Thomas Gann in the previously cited Minute Paper 3527-18

9

Ibid.

10 In reporting on the northern districts, Gann notes that it was impossible to reach the Maya communities inland

with food or medicine, and that pneumonia, as a consequence, was much more common among the Maya than among the Mestizo and Creole.

11

It should be noted that Gann notes the inaccuracy in the data supplied, given the remoteness of indigenous communities and the inaccessibility to information.

12 With permission to reproduce, Jesuit Archives and Research Center, St. Louis, MO., U.S.A.

13

Good Friday Homily delivered at St. Peter’s Basilica. April 10, 2020. Web. 3 June 2020. <https://www.catholicnewsage

ncy.com/news/full-text-fr-cantalamessas-homily-for-good-friday-97954>.

14 “Spanish Flu.” History.com Editors. 19 May 2020. Web. 3 June 2020. <http://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/1918-flu-pandemic>.

15

From the Minute Paper 3527-18 cited earlier

Price, George C. Address to the Graduates Claver College, Punta Gorda. 5 July 1966. Reel 3951. Belmopan:

Belize Archives & Records Service. Microfilm.