Events of history have solidified the Rt. Hon George Price as the founding political leader of the modern nation-state of Belize. Over time historians will gather the works, policies, projects and ideas and comb through them and assign his overall contribution a place in Belize’s relatively young existence. But this essay is about another would-be Belizean political leader, Assad Shoman. Outside of Mr. Price, Assad Shoman in my judgment remains the most intriguing of them all.

I shall not give a chronological background of Shoman since others who are far more familiar with these historical events have already done so elsewhere. Rather I would like to look at what could have been if Assad Shoman had been a Hugo Chavez.

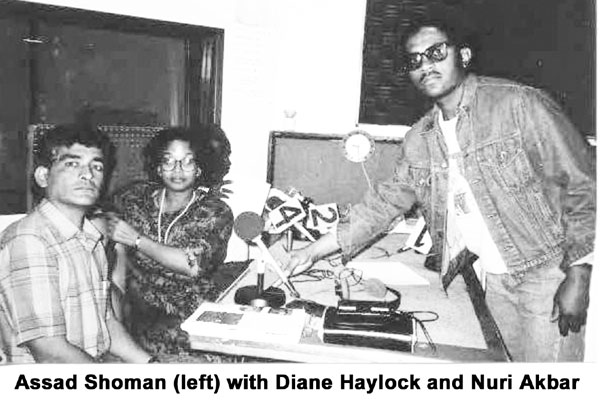

My only two working encounters with Dr. Assad Shoman were in 1989, when the Los Angeles-based BREDAA organization invited and hosted SPEAR for a week-long visit with the Belizean and activist community in Southern California. The following year, SPEAR reciprocated by hosting members of BREDAA in a series of events surrounding international Pan African Liberation Day in Belize.

During the 1980’s the organization SPEAR (Society for the Promotion of Education and Research) re-emerged after many years in a dormant state after the principal founders, Assad Shoman and Said Musa, were co-opted into the People’s United Party (PUP). SPEAR was organizing public forums on a regular basis and inviting regional and international activists like Caribbean writer George Lamming and Pan Africanist Kwame Toure (aka Stokely Carmichael) to Belize. SPEAR even ended up hosting the Hon. Min. Louis Farrakhan when he visited Belize in 1986.

BREDAA, which was made up of mostly young students at the time, was both impressed and intrigued. An unofficial working relationship began between the two organizations and we started to broadcast the various recorded SPEAR forums and speakers on the BREDAA-sponsored and produced popular radio show – the Belize Caribbean Pulse, via Pacifica stations in California.

Assad Shoman has written extensively, but his book that had the most impact on me as a young student was Party Politics. This was the first and only time anyone who had actually served inside the so-called Westminister system of government that was engrafted upon Belize by the colonialists, had publicly documented a critique and obliterated this model of governance from a scholarly point of view.

Shoman has also written on land tenureship, which remains at the foundation of Belize’s uneven distribution of wealth among its people and a bastion of corruption by various politicians over the decades.

Yet, despite this intimate understanding of the inherent contradictions, impediments and weaknesses of the Belize system of governance, Assad Shoman never organized a grassroots mass political organization to challenge the system with the goal of eventually replacing it, as some of his mentors had done. Shoman has had a front row seat to some of Belize’s most epic challenges, both internationally and domestically. He made international connections with some of the most progressive movements, organizations and governments around the globe, but none of this was used to build a local political front on the ground in Belize.

I am fairly certain Shoman fully comprehended that he could not change the system by mere intellectual discourse alone without direct social/political mobilization on the ground. None of his idols challenged the status quo and citadels of the privileged by merely being critical of it. The question beckons, what if Assad Shoman had chosen to organize a grassroots political mass movement, how would it have played out, and to what degree could it have changed Belize’s current conundrum?

When asked while on a visit to Los Angeles in 1989 if he had any future political ambitions the reply was, “No, we are not promoting ourselves as leaders of any movement.” Perhaps Shoman’s inhibitions at that stage were reflective of his earlier sting within the blood sport of Belizean party politics, where he experienced both the triumph of winning and the agony of defeat.

My sense is that Assad Shoman made his choices and struggled with how best to have an impact on his country’s political development. He is certainly not alone in grappling with this question. Over the years several political entities/third parties have emerged in the nation of Belize, but they remain peripheral, splintered and lack a nationally recognizable agenda or mass following.

Price’s recruitment of Assad Shoman, who held political views that were radically and diametrically opposed to his mixed-economy beliefs, gave credence to his visionary brilliance. By recruiting Shoman, Price was decapitating any potential for a third political force from the left to rise in Belize. Shoman’s very decision to join the status quo, however, could also be marked as the beginning of the end for any ideas Shoman may have held of challenging the political system. As his tenure in government clearly demonstrated, he had to battle with conformist inclinations and the institutional entrenchment of the “old guard” party hierarchy. In the end he left dejected, wounded and with permanent political scars. Perhaps Assad Shoman’s greatest dilemma was having one foot in the door and the other outside, essentially not fully committing to either. To this end, despite his best efforts, Shoman never came across as completely comfortable in the streets/’hood among the proletariat.

He has written critically of his Party Leader’s lack of any specific political ideology and saw this as an impediment to charting a coherent and unequivocal course for social, economic and political development. On the other hand, it can be equally argued that Shoman’s firm grasp of being an ideologue within a political organization that had no clear ideology, became a political death trap for the aforementioned.

Assad Shoman came of political age during a turbulent period where his socialist views had the best chance of germinating domestically. The entire region was convulsing, and the so-called Cold War had reached a fever pitch between the United States and the Soviet Union. There were other forces at work, including the United States’ policies toward the isthmus and Guatemala’s claim on Belize that made political options seemingly limited. Could it be that these considerations doomed any socialist political ambitions Shoman may have had in mind or entertained? Of course, only he can answer these questions. Nevertheless, there was no visible, serious attempt to explore/organize such a movement within the context of the Belizean experience.

While SPEAR was attacked by the right-wing elements in Belize’s political establishment in the 60’s and 80’s, nobody seriously believed that SPEAR had the potential or intention to evolve into a mass political movement that could pose a challenge to the two-party system. Indeed, as with the original SPEAR movement of the 60’s and co-option of Shoman and Musa by the PUP, other leaders from the group 1980’s circa were similarly absorbed by the UDP (United Democratic Party). Besides the sinister message of abandonment it sent to the younger generation who were watching, listening and being inspired, it makes one wonder what was the real purpose of the political rhetoric in the first place? None of it gained traction, and some of the proponents appear to have become even apologists for the very same system they had earlier chastised and denounced.

It is reasonable to conclude that Shoman has long given up on any political ambitions where the Belize liberation movement is concerned and has settled into writing and researching in another country. Nothing is mysterious about a person coming to terms with personal fate and deciding to move on with his/her life. I fully respect this right and will defend anyone to freely make that choice. But for the few giants who defied this natural law – Castro, Che, Bishop, Rodney and Chavez, Belizeans are still holding their collective breath waiting and yearning for the emergence of its version of Madiba! We are left to wonder what might have been had Shoman chosen the Chavista path.