December, 2020– When we think of cultural activists in Belize, those who readily come to mind include Andy Palacio, who played a major role in popularizing Garifuna music; Pen Cayetano, famous painter and creator of the punta rock genre; Sylvia Gilharry Perez, who works tirelessly in promoting East Indian culture; Christian Coc, the fearless fighter for Mayan cultural preservation, and Silvaana Udz, Kriol language advocate. And, indeed, all of these great men and women fully deserve the accolades bestowed on them. But notice that not one writer is listed among them. This is not because our writers have been any less active, but because we have not yet fully recognized that much of the work our writers produce are, in fact, expressions of cultural activism.

To borrow Busner and Arnold’s definition of cultural activism, it is an intermingling of “art, activism, performance, and politics that includes engagement with a broad spectrum of creative practice…as a means to challenge dominant ways of seeing and constructing the world.”1 In postcolonial Belize, the dominant imperialist cultures that have pervaded, as a result of our colonial history and today’s geopolitical realities, are British and Anglo-American. Therefore, we’ll see that from the earliest period of Belize’s literary development, our writers have challenged British or foreign dominance, even though they may not necessarily have done so consciously, or might not have used the term “activism” to describe their subversive writings.

Two of the ways by which Belizean writers have challenged the status quo and asserted their cultural identity are through their choices of subject matter and use of their mother tongues. These include, to varying degrees, Spanish, Garifuna, Maya Mopan, Maya Q’eqchi’ and Kriol. This paper focuses on the Kirol language and its deployment by Belizean writers as a form of cultural activism.

We begin with a poem published in 1920 by James Martinez. Written in Creole, the poem is titled “De Jazz Ban” and was published in Martinez’s book Caribbean Jingles, which was one of the earliest literary publications by a native Belizean. If you attended primary school in Belize in the 1980s or earlier, chances are you learned Martinez’ very popular poem “Success of Life.” In “De Jazz Ban’” the speaker is describing his first encounter with jazz:

De JAZZ BAN’

by James S. Martinez

I’d bin to lis’n lately, an’ hear de Jazz Ban’ play;

An’ goodness me! my narve dey nea’ly bus’.

Dey kick up such a squabble, an’ dey mek such lat o’ n’ise!

I never hear such instrimental fuss.

De instriments an’t many, as in de reg’lar ban’

An’ to look at dem yo’ never would suspec’

Dat de polish lookin’ Cornet an’ de slim an’ neat Trambone

Could ever raise such row as w’at dey mek.

Fus’ de Clarinet start squeakin’ some notes of discanten’;

Den de Bass begin to bellow out a few;

An’ de Trambone jine de chorus wit’ some slow discardant soun’

An’ de Drum begin to beat a bris’ tattoo.

An’ so dey scream an’ babble, each mixin’ in de row,

Antil de air is full wit’ deaf’nin’ n’ise.

Den jus’ like from a’ ’lectric, yo’ get a sudd’n shack,

As de Cymbal clash a lightn’nin’ like su’prise.

An’ de row is now quite heated; an’ dey have a big dispute,

As if dey’s gwine to en’ up in a fight—

An’ de Cornet start a bleatin’ an’ de Bass commence to roar,

An’ de Trambone blas’ an’ howl wit’ all his might.

So dey quarrel an’ dey squabble, an’ dey scream an’ screech an’ howl,

Till dey drap into a kin’ o’ stifflin’ groan;

An’ yo’ wander as yo’ lis’n, w’at is goin’ to happ’n nex’,

Den yo’ hear de Trambone give a dyin’ moan.

An’ so yo’ sit an’ lis’n, till yo’ head commence to swim,

An’ yo’ feel yo’self jus’ like yo’ gwine to drap—

Den yo’ hear an awful squealin’, an’ anadder startlin’ soun’

As de Cymbal mek a clap fo’ dem to stap.

An’ so de tune is finish—if tune it rea’ly was;

An’ de instriments is put aside to res’

An’ yo’ feel yo’ narve a trabbin’ an’ yo’ head a achin’ hard,

An’ yo’ t’ink to get some quiet is de bes’.

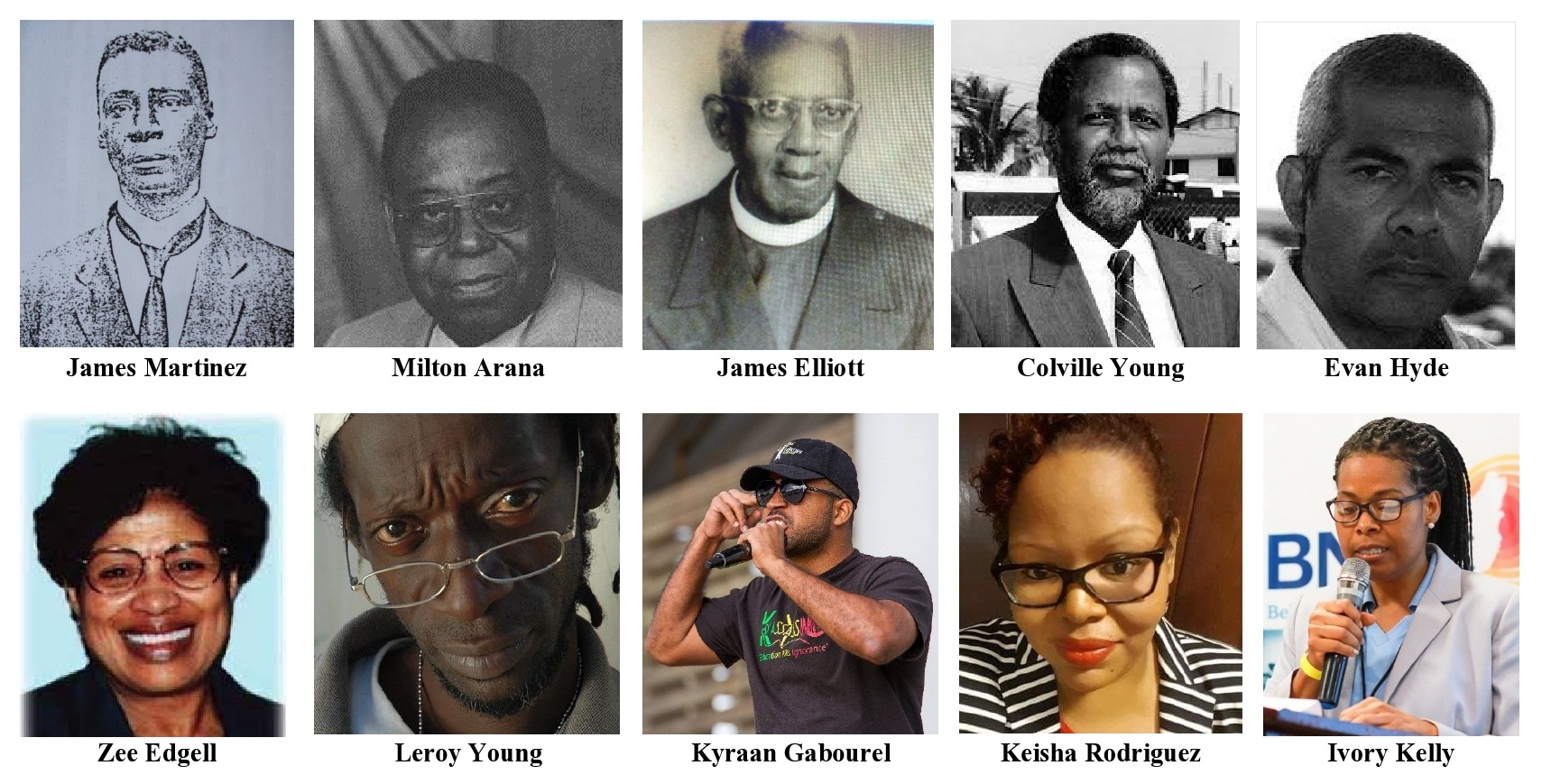

Martinez’s Caribbean Jingles was, as far as the research indicates, the first Belizean publication that utilized Creole extensively. As an aside, he was not a Belize City Creole, as one might have expected, but a Garifuna from the Toledo District in the south. And, of course, there are ways of explaining that thought-provoking irony, aside from the fact that Kriol was and still is the Belizean lingua franca, but that discussion is beyond the scope of this presentation. However, Martinez was one of the very few prominent poets, prior to the 1970s, who embraced Kriol. Others in that small fraternity included Milton Arana, James Elliott, and Colville Young. Most of the other leading writers did not write in Kriol at all, even though most of them were Creoles, and the majority of the population at the time spoke Kriol as a first language.

You see, those were the oppressive colonial days when Kiol was regarded as “bad English” or “a corruption of the English language.” It was associated with backwardness and lack of ambition, and school children were beaten for speaking it in the classroom.

In fact, if we read three of the earliest anthologies, namely, Some Poems of British Honduras22, Belizean Poets Vol 1, and Belizean Poets Vol 2, which were all published in the 1960s, we’ll find that among the 170 poems total, not a single one was in Kriol. Not even one word. Two of these three anthologies were published by the Government Information Service, and all three were endorsed by the official “establishment”. Therefore, since those anthologies contained what were obviously considered the best poems of the time, it is reasonable to conclude that this exclusion of Kriol represented the official policy, or at least attitude, of the “establishment”. So then, embracing Kriol as enthusiastically as Martinez, Arana, Elliott and Young did, was most definitely subversive. They were among our first cultural activists.

Next, we have an excerpt from Colville Young’s folk drama Riding Haas, which was written around 1970 and later published in the 1998 anthology Ping Wing Juk Mi: Six Belizean Plays. Widely performed in the ‘70s and ‘80s, the play is a superb depiction of one of Belize’s popular folk characters, Brer Anansi (or Brer Hanaasi), who is half man, half spider. Anansi—who, as we know, originated in West Africa and is a popular folk character throughout the Caribbean—is a trickster. He uses his brain, in the absence of brawn, to outwit the powerful Brer Tiger: indeed, a classic motif in Caribbean literature.

Creole pipple say when man no gat nutt’n fo ’e do,

’e go da savanna go tell cow morning!

So now dis da one time long before you and me dream fo barn,

Hanaasi feel idle an ’e mek up ’e mind fo mischief!

Hanaasi gaan da Woman Town,

Straightn ’e spectacle, look all ’round,

Quint pan di gyal dem, fresh as ever,

Boast to di crowd by Belize river

Dat ’e know how fo ride

Wid whip, wid spur,

Stick eena di saddle

Like any burr-burr,

Di gyal dem giggle an’ shout out,

Choh!

You think dem deh lie could-a fool we, no?

All you barn-days, we willing fo bet,

Hanaasi never set eye pan bridle yet!

Brer Hanaasi him staat to row,

’E bex till puff-up! Yerri im now:

Unu ’tap deh like pyam-pyam eena grass;

Tiger da mi faader best riding has!

In the 1970’s also, Evan Hyde published extensive works using Kriol, including the play Haad Time and his brilliant memoir, North Amerikkkan Blues. Similarly, Zee Edgell, especially in her first novel Beka Lamb (1982), utilized Kriol very effectively. And then in the 1990s through to this second decade of the 21st century, poets like Erwin Jones, Leroy Young, Kyraan Gabourel and other spoken word artists have been throwing it down and writing it down in Kriol, talking bout how “Life Haad Out Yah,” and Belizeans “Kyaahn stan di Presha,” but their only resort, it seems, is to “call di talk show”. See, for example, Erwin Jones’s Ghetto Food (2007) and 501 Spoken Word’s Poetic Narcotics (2019).

Throughout these 100 years, however, the versions of Kriol utilized in our literature have been, by and large, acrolectal and mesolectal Kriol—versions that are close to English. And this has been the trend throughout the Anglo-Caribbean: an expediency embraced by most writers who wish to reach a reading audience beyond our borders while retaining our unique Caribbean—and, in our case Belizean—voice.

And then in 2007, a monumental development took place here in Belize when the Kriol Council published the Kriol Inglish Dikshineri, after years of work developing a spelling system that made it possible for Kriol to be written in a standardized way. Publications directly spawned or enabled by this development have been the Kriol Council’s weekly column “Weh Wi Ga Fi Se,” published weekly in the Reporter newspaper, and Belmopanonline.com, as well as an extensive body of religious outputs by the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Belize (jw.org/en/library), creative works by authors such as Colin Hide (Growing Up in Old Belize, 2013) and the 501 Spoken Word poets, and an ever-increasing number of political, commercial and public service advertisements countrywide.

Then, in 2019, we had the short story “Stilbaan” (“Stillborn” in English). Published in my collection of short stories titled Pengereng, “Stilbaan” was originally written in English and co-translated into Kriol by Silvaana Udz and myself. In an essay that accompanies the story in the collection, I share some details about that process. I explain, for example, that in translating the story from English to Kriol, I made some choices that deviate from the Kriol Inglish Dikshineri and from the way Dr. Udz and some other Kriol advocates write Kriol; and I discuss my reasons for those choices.

The following is an excerpt from “Stilbaan,” a contemporary story that centers on the question of whether a woman ever is justified in excluding her child’s father from the child’s life. In the opening scene we meet Diana who, originally from Belize but now married and living in North Carolina, has just received an email from her first child’s father—after fourteen years of estrangement:

STILBAAN

Daiyaana

Daiyaana stayr pahn di eemayl sobjek fi wahn gud wail. Ih tink ih shuda dileet it. Ih stay deh fi wahn wail di kontemplayt it. Bot den ih chaynj ih main. Deep bret…nais ahn stedi. Ih sit op strayt eena di dainin chyaa ahn klik di eemayl oapm.

4/22/16

Dyaa Daiyaana:

Ah noa Ah di brok mi pramis. Ah sari fi di inchryood (Ah geh yo eemayl fahn di Chapl Hil websait). Fi tel yo di chroot, Ah noh eeven noa wai Ah di rait. Bot Ah ges Ah mi waahn yo noa dat Ah rait wahn leta tu ahn evri yaa pahn ih bertday. Ah goh da maas, lait wahn kyandl, den Ah kohn da mi aafis ahn rait tu ahn. Now dat ih wuda mi tern foateen dis yaa ahn ih bertday di kohn, Ah fain miself di tink bowt ahn eeven moa. Ah imajin ahn di play spoats, aal ih nee ahn elbo di stik owt laik mai wan dehn wen Ai da-mi da ayj (LOL). Ahn ful a lait tu, Ah bet, bikaaz shoarli hee mi wahn inherit yer honjrid-watt smail. Fergiv mi fi di bayr mi haat laik dis. Ah noh wahn tek op moa a yo taim.

Mi bes tu yo famili,

Omaar

P.S: Ah mi reeli did lov yoo, Daiyaana.

Daiyaana kloaz di laptap ahn waak oava tu di kichin windo ahn gayz owt eena spays. Ih ron di laas sentens chroo ih hed agen. Sodn-wan ih feel wahn erj fi kleen, ahn ih waak oava tu di stoav weh Erik ahn Fidel mi play laik dehn ferget agen laas nait.

Widowtn bada fi put aan di raba globs, Daiyaana tek di pees a fail paypa weh mi splata wid food aafa di jrip pan dehn ahn jrap dehn eena di garbij. Ah mi reeli did lov yoo, Daiyaana. Ih ful op di sink wid hat waata ahn staat kleen di fos pan. Sloa, sloa wan, ahn stedi stedi, ih skrob jentl pink swirlz wid di

Brillo pad; ih di foakos…ih di breed deep…di setl ihself eena di moament—ten yaaz a Vipasana meditayshan gud ahn perfek. Owtsaid di kichin windo, wahn mail breez rosl di redish leef dehn pahn di daagwud chree ahn kaaz Daiyaana fi rimemba wahn nada faal seezn fifteen yaaz abak. Ah mi reeli did lov yoo,

Daiyaana. Di pan slip owta ih han ahn jrap pengereng pahn di floa.

And now, as we come to the end of 2020, marking a century of Kriol usage in our literature, I, as a teacher of composition and creative writing at the University of Belize, am exceedingly glad and encouraged to note that Belizean students have increasingly been incorporating Kriol into not only their poetry and fiction but essays as well, particularly when dialogue is used. It seems to have become almost instinctive for some students to thus utilize not only our Kriol lingua franca but other mother tongues, especially Spanish, Mopan and Q’eqchi. And while some might see cause for alarm in this, there is overwhelming evidence that not only is this psychologically healthy but when harnessed properly, mother tongue usage aids rather than impedes second-language acquisition.

I am also greatly encouraged that one of the questions in which students in my creative writing classes at UB have been most interested is not whether they should incorporate Kriol into their short stories and memoirs but how much: “We know Creole usage is the norm in Belizean and Caribbean literature. But Miss, are there guidelines for how to do this?” Unfortunately—or perhaps fortunately—I have no specific guidelines, textbook or formulas to offer them. But what I do have is one hundred years of Belizean examples to point them to.

And speaking of examples, I’d like to point out that next year will be the 50th anniversary of the publication of Evan X. Hyde’s North Amerikkkan Blues, which I mentioned earlier. In that memoir, Hyde’s use of “a kind of Creole,” as he describes it, is a superb example of simultaneous mastery of the Queen’s English and assertion of the writer’s unique Belizean voice. In 1995, the memoir was re-published by Angelus Press in Hyde’s X-Communication: Selected Writings, but its original publication was in 1971. So, fifty years next year. I hope there will be a celebration or re-examination or re-release, or something. Shouldn’t let that go right soh.

I can’t end without thanking the staff of the National Heritage Library in Belmopan and, by extension, the National Library Service and Information System, for assistance with access to some of the texts mentioned, especially the older ones that are no longer in circulation.

Notes

(Endnotes)

1

Michael Buser and Jane Arthurs, “Cultural Activism in the Community”

Culturalactivism.org.uk , 2013

Bradley, Leo. Ed.

Some Poems of British Honduras, 1962

——————————————

Author’s Note:

Ivory Kelly is the author of Point of Order: Poetry and Prose and Pengereng, a collection of short stories in English and standard Belize Kriol. Her short stories have also been published in journals and anthologies in the Caribbean, the UK, the US, Mexico, Brazil, and Belize. For more information, visit her website at www.ivorykelly.com