BELIZE CITY, Tues. Apr. 21, 2015–Financial Secretary Joseph Waight told Amandala this morning that the reason the Government of Belize introduced the new PetroCaribe Loans Act—now the subject of public debate—is that there is a major difficulty with the PetroCaribe loan transactions when it comes to meeting the requirement of the Finance and Audit (Reform) Act of 2005, which stipulates that any loan agreement of $10 million or more has to be first approved by Parliament before any such commitment involving public funds is made.

Waight told us in an interview today that, “the difficulty with the PetroCaribe program is that we don’t know how much is going to come in terms of flows at any one time…”

What we gleaned from our interview with Waight, though, is that the central issue is not that Government cannot take the loan request to Parliament before it is finalized, but that it would require a drastic alteration of the customary meeting cycles of Parliament—an important concession, since the Opposition People’s United Party has said that it would be willing to go to Parliament as often as is required to give attention to the PetroCaribe loan agreements.

Amandala had the chance to review the 2006 legislation enacted by Jamaica, which governs a special PetroCaribe fund which that country had established to set up a framework for all transactions related to PetroCaribe funds. That legislation refers to a promissory note that Jamaica must send to Venezuela for specific transactions.

What is a promissory note? A promissory note documents a promise from the borrower (in this case Belize) to repay a loan from a lender (in this case Venezuela). The note will state the amount owed, how interest will be calculated, and the payment terms. (www.onecle.com)

The Financial Secretary told us that Belize also issues promissory notes to Venezuela. We learned of this when we questioned Waight to find out the point at which the Government does know what the loan value from Venezuela would be.

Waight said that after the financial transactions related to the purchase of fuel from Venezuela are complete, the Government would have an idea what the borrowed portion would be. Waight further said that the period which stretches from the point the fuel order is placed, to the time money comes into the Government account, could span two months. After this, promissory notes are issued.

He told us that the last batch of promissory notes sent to Venezuela covered November and December 2014 and January 2015, and totaled roughly $30 million. Another batch would be due to be sent over around mid-year.

So, we asked Waight: why can’t the Government go to Parliament at the point when it is ready to dispatch those promissory notes?

Waight said that there is not a regular meeting of Parliament, so we understand that to mean that the cycle of meetings of Parliament would have to be changed to facilitate more regular meetings to review the PetroCaribe loans before the deal is sealed.

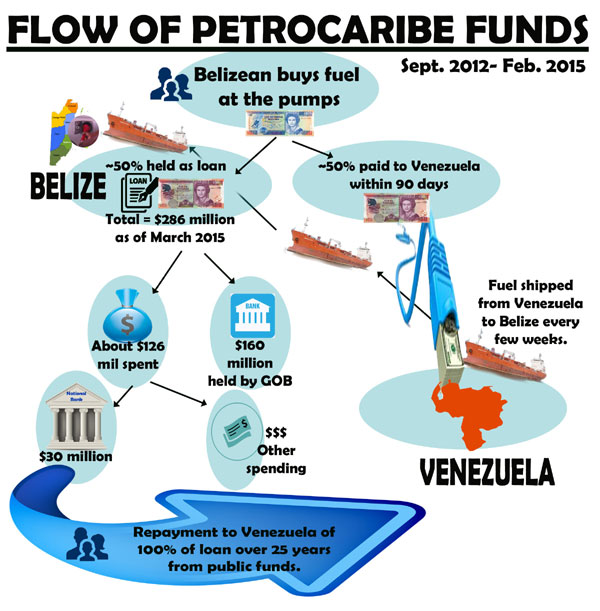

The PetroCaribe loans now constitute a major part of Belize’s external debt. The monthly economic reports published by the Central Bank of Belize indicate that Belize had received roughly $198 million from Venezuela under the fuel accord up to the end of January 2014, and by the end of January this year, 2015, that amount had grown by over $90 million to roughly $291 million.

Of note is that this is the biggest block of debt Belize holds, second only to the billion-dollar Super-bond. Belize’s debt to Venezuela has surpassed its borrowings from Taiwan, the Inter-American Development Bank and the Caribbean Development Bank – the other big lenders. However, of all the external loan commitments on the books, it is the one with the lowest interest rate – a nominal 1%.

We asked the Financial Secretary whether he could identify with any of the concerns raised by the trade unions, the business community or any of the other persons who have expressed grave reservations about the new PetroCaribe Loans Act. Waight pointed to concerns that have been raised that the new legislation places no limit on how much the Government can borrow from Venezuela or spend out of those proceeds without first getting approval from Parliament.

He said that looking at that issue alone, he could see how that could be a concern, but added that this has to be looked at in the whole context of the borrowing, as well as the fact that Belize has to maintain limits in its debt ratios.

Another concern, Waight said, is the decision by the Government to make the PetroCaribe legislation retroactive. Waight said that the Government has the prerogative to change laws, and it exercised this power when the court found that the first nationalization of Belize Telemedia Limited was unconstitutional. It changed the law to nationalize the company a second time.

Widespread opposition to the PetroCaribe law also springs from sentiments that the safeguards built into the Finance and Audit (Reform) Act in response to pressure from social partners are now being abandoned to facilitate the PetroCaribe loans.

We raised this issue with Waight as well, and asked him whether there would be any safeguards against abuses of the funds still in place. He said that contracting procedures for projects such as infrastructure projects, which would come under capital spending for which the PetroCaribe funds are sometimes earmarked, still go through the same procedures as other such projects.

“We get a little bit more unclear when it comes to giving out social assistance,” Waight said.

The question to be asked, then, would have to be whether the purported beneficiaries are as claimed, Waight noted. He said that the Ministry of Finance does not disburse funds to politicians, but directly to beneficiaries and suppliers. Waight conceded that it is conceivable that they may end up with “ghost beneficiaries,” so the Government requires documentation with copies of Social Security cards, and checks are made out to individuals on that basis to ensure that payment is being made to a real person.

The PetroCaribe law permits the funds to be used for specific projects such as capital projects and social assistance to the poor, but it also adds a final clause, that the funds can be used for other “legitimate purposes.” This has also caused a level of skepticism, in that there are those who say that this could open the door for the current administration to exploit the funds for pre-election campaigning.

The Opposition People’s United Party had publicly alleged, after the ruling party swept up virtually all seats in the countrywide municipal elections of March 2015, that the Government bought the elections with PetroCaribe funds – a charge which the ruling party has categorically rejected.

Waight told us, when we asked him about the clause which permits any “legitimate spending,” that “there has to be some element of trust…” He added that if a politician decides to spend money for illegitimate purposes, people will find out because “Belize is too small.”

Such illegitimate purposes, he said, would be for self-gain.

We asked the Financial Secretary whether Belize, in crafting its PetroCaribe law, looked to see what had already been established in other jurisdictions in the region. Waight said that he is unsure whether any government official did this review.

In the case of Jamaica, a special fund is established, managed by a board of directors, which receives all PetroCaribe funds and does all the necessary payouts of those monies. That fund is subject to a professional annual audit and it remains under policy direction of the executive.

In the case of Belize, though, our law speaks of a special account – not a special fund, and there is no board in charge of managing the PetroCaribe funds. As things now stand, the managing authority is really the Ministry of Finance.

Waight told us that while the funds are kept in a special account, that account is merely a holding account, and funds are taken from that account when needed and placed into a general account for use.

When we asked him whether an audit has ever been done of that account, he indicated that none has been done for the special account. Waight said that this special account just shows “ins and outs,” and it registers about 12 to 15 deposits over a year and 7 to 8 withdrawals of about $5 million to $10 million at a time.

When the new PetroCaribe law was introduced in March, some members of the public had expressed concerns that the Auditor General would have no oversight of those funds, but Waight said that this is not the case. He said that the PetroCaribe funds still form part of the Government’s consolidated revenue fund, which is subject to scrutiny by the Auditor General.