BELIZE CITY, Wed. Feb. 23, 2022– A 9-page letter penned by the Commissioner of Indigenous People’s Affairs, Greg Ch’oc, was sent to the Deputy Registrar of the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) on February 14 in an effort to refute the claims made by the Toledo Alcalde Association (TAA), the Maya Leaders Alliance (MLA) and the Julian Cho Society that they had not been consulted prior to the government’s recent submission of the Free, Prior, Informed Consent protocol to the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ).

In the letter, Commissioner Ch’oc stated that the government considered the completion of the FPIC protocol a “historic achievement,” despite the abundance of opposition to its contents and to the manner in which it was submitted. While he said that the protocol “paves the way for respectful dialogue with the Maya Villagers”, it is to be noted that those villagers are represented by a chosen alcalde, and the alcaldes of the respective villages have in turn opted to be collectively represented by the TAA.

According to Ch’oc, however, the government recognizes only individual alcaldes and not a collective body.

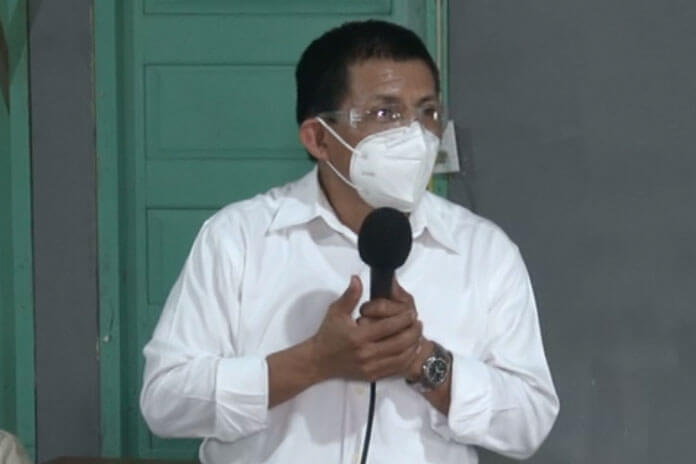

“An alcalde functions at the village level, as I said, so Mr. Bah or the members of the executive of the association cannot come here and hold an alcalde’s court, for example, unless you villagers allow it or accept it, but I have been to almost 24 villages, and most of this, in fact, all of the villagers have said to me, ‘our village members are the decision-makers, we come to a meeting like this and we make decisions. When there is a big issue that comes we come to a meeting and we make decisions and our alcalde executes that. Out chairman executes that’, that is what the villagers have said to me …” Ch’oc had stated during a public address.

He added, “I have not heard any of the villages telling the government, ‘this is the organization that represents us’. That’s the reason why we have taken the position. So, the government of Belize in this policy document recognizes the alcalde system.”

One of the primary issues of contention in regard to the FPIC protocol is the terminology used in the document, which will determine whether the government is required to get the consent of villagers prior to carrying out any activities that involve the use of their lands, or whether it only has to consult them. Internationally, the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples makes provision for Free, Prior, and Informed Consent. Commissioner Ch’oc has said, however, that they are championing a free, prior, and informed consultation protocol.

Ch’oc has rightly stated that consultation must be free, prior, and informed in order for consent to be obtained from those communities, but maintained that the protocol is for consultation, and is not a consent protocol.

“Some have said that it has to be a consent protocol but we have said that it should be a consultation protocol, because under international law it is clear that the government must consult, but that must be free, prior, and informed … so that if you decide that you accept it, you would have understood the negative, the positive, all that you need to understand to say, ‘I will accept it, so if anything goes wrong you have nobody to blame but yourself,’” Ch’oc had told residents of San Antonio village, which he recently visited.

Commissioner Ch’oc, has seemingly been on a public tour across the Maya communities along with Minister Dolores Balderamos Garcia and gave those comments during a San Antonio village meeting. During a similar meeting in San Pedro Colombia, he stated, “If you’re doing a process to accept, then there is no process to say, ‘I don’t want it.’ That was what was wrong with the first protocol. It is a protocol that geared the community toward consenting. There was no option to say ‘no, we don’t want it.’ And I want to turn you to the section, number 12, under Customary Decision Making. Part 12 number 16, is what the Government of Belize has recognized. It is unprecedented. It is perhaps the first in the Americas. It says if consent is withheld, and a Maya village or villages are clear that they do not consent to the proposed administrative measures, there the consultation process is over. And no administrative action may be taken. It’s done. You said no. So, it is consultation, because it has to be free, prior, and informed. So, when you say, I consent, it is because you fully understood why you accepted. And if you say no, likewise you fully understood why you say no.”

The representatives from the Ministry of Indigenous People’s Affairs have said that there would be some instances where consent from the Maya communities would not be needed for the government to take action—in cases of emergency and where reserves of government-owned minerals are concerned.

During an interview in late January, Minister Balderamos Garcia stated, “The constitutional authority of the Government of Belize over all land in Belize is not affected, and you can go and read that right in the consent order itself. The government is not giving away when it comes to oil drilling etc. Anything in the ground is owned by the people of Belize and administrated by the government.”

The Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights in the United Nations, in referring to FPIC protocols, states, “The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples requires States to consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them.”

Article 32 of that declaration refers to, “The undertaking of projects that affect indigenous peoples’ rights to land, territory, and resources, including mining and other utilization or exploitation of resources.”

Article 28 makes provision for the recovery of lands. It states that indigenous peoples who have unwillingly lost possession of their lands, when those lands have been “confiscated, taken, occupied or damaged without their free, prior and informed consent” are entitled to “restitution or other appropriate redress.”

The parties will be back before the CCJ at a compliance hearing scheduled to take place in a few months.