BELIZE CITY, Thurs. May 18, 2017–The country of Belize has gone through some trying times, and while it is often described as “a peaceful haven,” it has battled and continues to battle conflicts both within and without. Trans-boundary problems have been among the most challenging. Although Belize prides itself on being an independent nation state, imperialism has vastly influenced what Belize is today. Not surprisingly, there are those who contend that the best of Belize is gone, and just decades after independence, despite a transformed and modernized landscape, life is harder for many families in today’s Belize.

Sidney “Stretch” Lightburn points to the fact that more and more Belizean families are unable to afford to take family vacations today as one demonstration of how things have regressed, as, in his view, the days of abundance are gone.

“That generation [in which he was raised] had the best of Belize, because remember before that there was war and after the war, we had things pretty good here; that period between 45, 50, 60…” he said.

“You could afford to go [on regular family vacations]. You can’t today… In the old days families used to get together, you would take your pots and pans and things, get a lighter and sail off to Mullins River and get there Saturday night, settle in and Sunday continue into the week. They would collect firewood and get fish when the fisherman comes… buy plantains and all that to cook. Potato pound and bread pudding and cassava pudding would be made for dessert. Today, you can’t afford that,” Lightburn added.

“You don’t cook under the coconut tree like those days. You go to a restaurant. What has that done for poor people? That is missing. Everything was in abundance then,” he continued.

“It took us 30 to 35 years to get us where we are right now,” Lightburn said, adding that things started to transition in the late 40s, early 50s.

Devaluation—a decision of the British which meant that the Belize dollar, pegged to the US dollar, would no longer have parity with the US dollar—changed things drastically for Belize in 1949. It was sudden, Lightburn recalls. Since the British had devalued their currency earlier that year, the British Honduras dollar, being pegged to the US dollar, had more value and the decision made to devalue the British Honduras dollar and delink it from the US dollar served the economic interest of some of the British. In 1976, the link with the US dollar was reestablished at BZ$2 to US$1. That peg remains intact today.

“The situation is that the Governor was telling people that [devaluation] wasn’t going to happen—and all of a sudden it did. And that’s where the [People’s United Party] kicked off….the man holler. ‘Give me back me shilling with the lion pan ah!’ ‘Give me back my dalla!’ ‘Dalla fi dalla!” he said.

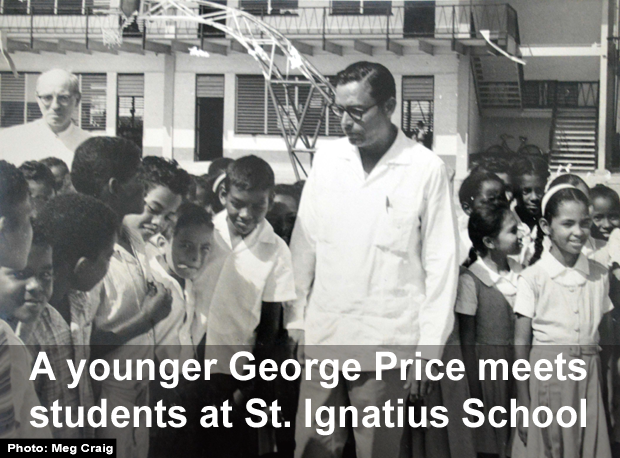

We were able to access a published reply to the Governor’s devaluation, which we obtained from Meg Craig, a sister of George Price who maintains personal archives of official photos and documents.

“Give us back our dollar. Give us independence,” the People’s United Party demanded.

Lightburn recalled that people could do a whole lot with a dollar back in those days: school fees for primary school were 5 cents a week; you could get a whole lot of bananas out of 5 cents too.

Imported items like Wood and Dunn butter and cheddar cheese got more expensive, but education remained affordable, he recalled.

“Everybody went to school and they had truancy officers to ensure that if they catch you in the street, you would be sent back,” he said, recalling the use of the “tambran whip” for those who persisted with breaking the rules.

“There was stronger discipline then. I would go through those whippings again. There is nothing wrong with it,” said Lightburn.

Lightburn believes that the introduction of television has adversely changed Belize. In his time, British Honduras/Belize enjoyed a colorful live entertainment landscape. They used to go to the Memorial Park where bands would play world-class music on a regular basis. The main entertainment they had as kids was the movies at Palace Theatre, which had matinee three times a week on Sundays, Wednesdays and Fridays. Two people would be charged 15 cents.

“There was a little politics with the two people in deciding who will put 8 and who will put 7 cents”, he jested.

Back on the topic of television, he compared it to today’s social media.

“When we had entertainment, it was like two or three days a week. This [television] is every night! Too much of one thing is good for nothing. For me, I don’t watch too much television,” he said, adding that he did not have a television set in his household until after migrating to Canada in the 60s.

“If you go to a very wealthy family’s home, you do not see a television. It’s there but you don’t see it. They talk about money and debentures! [They think that television] is for the riff-raff. Rich people learn about making money, while others are taught how to count it. That is the design,” he said, recommending the book, Dark Money, which he said sheds a lot of light on this.

“Follow the money! I look at the buildings being built [in Belize] and I look at who is building these buildings. Many are being built by the Asian community,” he offered.

“I think of a hurricane. Every Chinese man in Belize can go to shelter—they won’t send them to public shelters… Those people are ace business people because where they come from is not like here… You never see anyone but a Chinese behind the cash register,” Lightburn said.

Although there have not been very many controversial Asian characters in Belize’s history, Lightburn recalls some controversial Americans and Europeans who came on the scene.

He recalls names like Dvorak, who traded lobster, reselling what he bought in Belize to buyers in New Orleans, and Buratti, who had fled from Cuba and later opened a fishing lodge in Belize, as well as “Little John, Little John,” an American who was said to be among a group of people who allegedly raided Caracol.

“Notwithstanding that, the British might have gotten their share way back…” he suggested.

Then there is the story of one Dr. Berry, an American who was trying to export forestry products. He raised wages considerably, way above the average rate of 36 cents per hour. He was the money behind Ned Davis, an American who had started logging works down in Deep River, Toledo. He also acquired what was called “Clover Leaf farms,” that had belonged to the Hofius family, near Mile 4 on the Philip Goldson Highway, Belize City, which now belongs to the Courtenay family.

Lightburn said that Dr. Berry found out that something was wrong with the way the money was being handled, so they took him to court and charged him with fraudulent conversion. He used to have to carry out slop buckets when he went to jail, as was the common practice for prisoners at the time, Lightburn said, adding that this all happened in the 50s.

Lightburn also recalls an incident involving arms smuggling to Cuba. Some foreigners and Belizeans were involved with a boat running guns to Cuba during the Bay of Pigs conflict (around 1960). The lighthouse keeper on Caye Bokel saw some suspicious movements and notified the Governor. Some guns had been buried on the island. They were found and as a result deportation orders were issued to the suspects, although some had those orders rescinded, Lightburn narrated.

“Belize started to get on the map slowly and here we are today, but we still look at ordinary folks struggling!” Lightburn lamented.

“Those who came were seeking the wrong kind of economic opportunity. Quick money to ship arms to Cuba, and drugs…” he said, recalling another investor, Victor Stadter, who came on the scene in the mid to late 50s/early 60s, had bought land in Chunox, Corozal. He was suspected, even by official sources, to have been involved in drug-running, although he denied it.

In 1971, Stadter became famous for masterminding the jailbreak of Joel David Kaplan, a convicted murderer who was serving a 28-year sentence, from a Mexican maximum security prison. Columbia Pictures released a movie—Breakout—in 1975, in which the famous Charles Bronson starred in the role of Stadter, who was the pilot.

As is the case with all stories from this era, politics and the Belize-Guatemala issue are always a feature in the narrative.

Lightburn said that the Belize-Guatemala issue “was always a kind of strong point for the Opposition.” He recalls hearing of the activism of the late Philip S. W. Goldson back in the early 60s and his Billboard piece titled “Seven Days to Freedom,” penned on Goldson’s return from a visit to Guatemala during the Arbenz presidency. Along with Leigh Richardson, Mr. Goldson was sentenced to one year in jail with hard labor for what the British colonial authorities deemed “seditious intention,” because of a statement in the Billboard that was supposedly hinting at a planned revolution. All this happened in the context of the push by the People’s United Party for the independence of British Honduras (now Belize).

There were also persistent rumors that George Price, dubbed The Father of Belize’s Independence, had been trying to sell out Belize to Guatemala, which some believe was British propaganda intended to retard independence.

“To me, it was a very touchy subject, in terms of bringing up an issue politically, and that may have been one of the reasons that… that remains the same even today,” Lightburn said.

“There was also talk about doing a Federation of the West Indies. I always wonder how that would have played out had that happened,” he later said.

Whereas Goldson lost at his sedition trial, Price, defended by W. H. Courtenay, won. There was a political meeting on the grounds of the Majestic Theatre, and Price gave a speech in which he mentioned about the Queen of England parading in New York and that people had “rained down” toilet paper on her, “and you know what toilet paper was used for,” he added. He was arrested and charged as a result, but the case fell through.

There was an accusation that Price was trying to sell the country to Guatemala. There was also controversy over a suggestion from Guatemala that Belize should use that country’s passport.

“There was a meeting in London, and Price had met with the representative to England from Guatemala (Jorge Granados). Somewhere along the line George had taken his crowd, his delegation to meet with this man to talk about trade from Guatemala to Belize and the man had mentioned changing up the Belize passport to a Guatemalan passport and that broke up the meeting,” Lightburn said, recalling what was being discussed in the streets at the time, around 1957.

Even then, there were serious cross-border tensions between the countries, he conveyed.

At one point, the then president of Guatemala (Miguel Ydigoras Fuentes, 1958-1963) visited Benque and said he had a friend to visit in San Ignacio, and a police sergeant, David Neal (who was once Lightburn’s music teacher), turned him back. Lightburn said that Ydigoras was going to visit an unnamed person when he was ejected from Belize. It was never revealed to him who that person was.

There are two major issues that concern him today, and the Guatemala issue is only one of them. Lightburn does not support Belize going to the International Court of Justice on the Guatemala issue.

“We don’t have any argument. The borders are there intact. I don’t want to hear anything!” he said.

He said that Britain and America don’t care; they want one big Central America.

Secondly, there is the issue of Donald Trump’s rise to the US presidency and his stance on immigration.

“Now there is a new thing happening. How is it going to affect us when Trump decides to ship all those people back who have no money or status? It could be hell; not only that, the people they are shipping back to Honduras and Guatemala will come here… The world is changing and changing fast,” he warned.