BELIZE CITY, Thurs. July 30, 2015–Belize and Guatemala have been in territorial talks under the auspices of the Organization of American States (OAS) since 2000, and while OAS officials said in the Tuesday night forum, dubbed “Culture of Peace Forum”, that we are very close to solving the age-old dispute, the extent of Guatemala’s claim—deemed by all Belizeans to be unfounded and unjust—has still not been clearly defined.

We understand from Foreign Affairs officials that Guatemala’s last written communication staking claim to half of Belize, from the Sarstoon to the Belize River, said in another breath that Guatemala is reserving the right to resurrect its claim to “all of Belize.” In fact, this is reflected in the country’s new passport, which has a dotted line along the full length of the country’s western border with Belize.

When we probed our sources within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the matter, we were told that they do not know exactly what claim Guatemala will bring, if the matter is voted for adjudication at the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Voters who are expected to endorse the ICJ process in national referenda to be held in Belize and Guatemala on dates yet to be announced will also not have this clear in their minds when they go to cast their ballots—a point of concern raised by some persons who flatly reject the ICJ mode of resolution.

When Belize and Guatemala signed the special agreement (or compromis) to have the claim adjudicated at the ICJ, the parties agreed, under Article 2, that they would ask the ICJ “to determine… any and all legal claims of Guatemala against Belize to land and insular territories and to any maritime areas pertaining to these territories, to declare the rights therein of both Parties, and to determine the boundaries between their respective territories and areas.” (Emphasis ours.)

The uncertainty as to exactly what claim Guatemala would bring is reflected in the referendum question, outlined in the compromis:

“Do you agree that any legal claim of Guatemala against Belize relating to land and insular territories and to any maritime areas pertaining to these territories should be submitted to the International Court of Justice for final settlement and that it determine finally the boundaries of the respective territories and areas of the Parties?” (Emphasis ours.)

We note that while the special agreement says that putting the matter before the ICJ would mean that the ICJ would “determine finally the boundaries of the respective territories and areas of the Parties…” Belize continues to insist that its borders, as set out in its national constitution, are defined in the 1859 Boundary Treaty.

Meanwhile, Belize’s Foreign Affairs Minister Wilfred “Sedi” Elrington, said at the Tuesday night forum that Guatemala sought to repudiate the 1859 Treaty “and the boundary line it created…”

However, the very first article of that treaty makes it clear – that the boundaries of the country now known as Belize did not originate in 1859. The boundaries were established at least a decade earlier, and the document speaks of the existence of those boundaries even before the year 1850 began.

In the treaty, Britain and Guatemala declared that, “…the boundary between the Republic and the British Settlement and Possessions in the Bay of Honduras, as they existed previous to and on the 1st of January 1850, and have continued to exist up to the present time, was and is as follows…” (Emphasis ours.)

It went on to detail where the border between the countries lies:

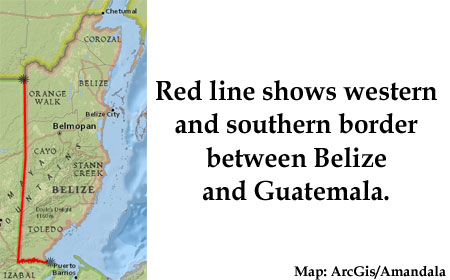

“Beginning at the mouth of the River Sarstoon in the Bay of Honduras, and proceeding up the mid channel thereof to Gracias a Dios Falls; then turning to the right and continuing by a line drawn direct from Gracias a Dios Falls to Garbutt’s Falls on the River Belize, and from Garbutt’s Falls due north until it strikes the Mexican frontier.”

In the treaty, Britain and Guatemala both “agreed and declared” that all the territory to the north and east of the line of boundary belonged to Britain and the territory to the south and west to Guatemala.

It has been widely argued that Britain’s failure to build an access road for Guatemala is the reason why Guatemala no longer accepts the treaty.

Article VII speaks of an agreement between the countries to “…conjointly to use their best efforts, by taking adequate means for establishing the easiest communication (either by means of a cart-road, or employing the rivers, or both united, according to the opinion of the surveying engineers), between the fittest place on the Atlantic coast, near the settlement of Belize and the Capital of Guatemala…” for commerce by both parties, and added that “…the limits of the two countries being now clearly defined, all further encroachments by either party on the territory of the other will be effectually checked and prevented for the future.”

Of course, the treaty did not stop incursions. Ironically, Elrington told the media on Monday that it was Guatemala that had complained of incessant incursions by the British back then, due to the expanding logwood trade. We note that today, it is Belize that is complaining of incessant incursions, linked to illegal logging, xate extraction, gold panning, illegal fishing, and the looting of archaeological artifacts.

In November 1980, in the months before Belize received its independence from Britain, the United Nations passed a resolution on the Question of Belize in relation to its ensuing independence.

Clause 5 of that resolution “urges the Government of the United Kingdom, acting in close consultation with the Government of Belize, and the Government of Guatemala, to continue their efforts to reach agreement without prejudice to the exercise by the people of Belize of their inalienable rights and in furtherance of peace and stability of the region and in this connexion, to consult as appropriate with other specially interested.”

Clause 9 of the resolution “calls upon Guatemala and independent Belize to work out arrangements for post-independence cooperation on matters of mutual concern…”

In November 2012, Amandala had a chance to interview UK Minister of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Hugo Swire. We told the minister that there are some Belizeans who say that it is the British who left Belize with this problem and that Guatemala should settle its issues with the British—not with Belize.

We live in 2012 and the only ones that can solve the problem, he said, are Guatemala and Belize – not the UK, he insisted.

A report titled, Background and Study of the Special Agreement between Guatemala and Belize to Submit Guatemala’s Territorial, Insular and Maritime Claim to the International Court of Justice, by Gustavo Adolfo Orellana Portillo, and appearing on the website of Guatemala’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs says, “The compensation mentioned in article VII of the 1859 Convention was not carried out, and on 5 August 1863, a Convention was signed whereas: ‘…Her British Majesty undertakes to request that her Parliament authorizes the payment of FIFTY THOUSAND POUNDS STERLING to fulfill the obligation entered into according to article VII of the Convention of 30 April 1859…’”

Portillo wrote that Britain argued that Guatemala did not ratify the supplementary convention of 5 August 1863, and so Britain “unilaterally resolved that the government itself was absolutely exonerated of obligations.”

He added that, “The Guatemalan Constitution of 1945 declared that Belize formed part of Guatemalan territory, and that negotiations leaning to its reincorporation were of general interest. This resulted in an immediate British protest, in the sense that Belize was British territory and that its boundaries had been established by the 1859 treaty.”

See pertinent web links:

Compromis: https://www.oas.org/sap/peacefund/PeaceMissions/SpecialAgreementBetweenBelizeandGuatemala.pdf

Text of the 1859 Treaty: https://amandala.com.bz/news/1859-boundary-treaty/