BELIZE CITY, Wed. Apr. 22, 2015–The Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) made major progress this week in brokering a resolution of a decade-old legal struggle between the Maya of Toledo and the Government of Belize when it handed down a consent order, reaffirming the 2010 decision and orders issued by then Chief Justice Abdulai Conteh, firstly affirming that indigenous Maya land tenure does exist in Toledo and also mandating the Government to take affirmative action to protect Maya rights.

The Government had appealed Conteh’s 2010 decision. When the Court of Appeal heard the case, it abandoned the orders which Conteh had made, but upheld the finding that the Maya do have customary land tenure.

Neither the Government nor the Maya were happy with that decision, and so they appealed to the CCJ. Even ahead of the CCJ hearings scheduled for today, the parties had reached a settlement—except for the question of monetary damages, proposed at roughly $1.5 million, which the Maya insist the Government must pay.

“Today, what is important is that the Government finally admits that they were wrong. This land is in fact ours – we have never changed that position. That has always been what we have asserted as a Maya people…,” said Cristina Coc, spokesperson of the Maya Leaders Alliance (MLA), one of the parties to the CCJ case. She was speaking to about 500 Maya assembled at the Belize Biltmore Plaza Hotel in Belize City, immediately after the CCJ proceedings.

Coc recalled that when she was a little girl, she heard the late Maya activist, Julian Cho, say: “We have been to the mountain; the mountain must come to us now…”

James Anaya, Human Rights professor at the University of Arizona, said that he came to Belize 20 years ago, when he met Cho and heard him utter those same words.

“Going to the mountain is making that struggle, doing what it takes to go up that mountain and reach the top—but that’s not enough… ‘The mountain must come to us:’ I think he was saying, and today I think that mountain came to you, that mountain being the court – the Caribbean Court of Justice that rendered an order or judgment affirming your rights over your lands and resources, according to your customary land tenure, saying that that right to the lands is one that has existed, not one that has been granted, and that is guaranteed by the Constitution,” Anaya told the Maya.

“Our highest court came here to hear your case, to hear your concerns, to hear what you have been struggling over for these many years. And we have to say congratulations to the Government of Belize also and to all the people of Belize because what has happened today is that an order was read by the president to the court, the president of the Caribbean Court of Justice, entering an order – a consent order, so it’s something agreed upon by the Government and by your leadership on your behalf…” said Antoinette Moore, SC, lead counsel for the Maya.

“That has gone for the last ten years through the courts, through the regional human rights bodies, through the courts of Belize and until now it has reached the last, the highest, that mountaintop in terms of the courts, the highest court; there is no other court, and they ordered, on consent of the parties—the Government agreed consenting to the order along with your communities—that your land rights are affirmed and are recognized,” Moore added.

“Now comes the work of seeing those rights implemented, of seeing the government actually make good on that commitment, of seeing the government officials change their behavior in their daily relationship with you, of seeing the government acknowledge the specific areas that you use and occupy,” Anaya urged.

He noted that the Maya of Toledo are a part of a global movement seeking recognition for indigenous peoples’ rights.

Government concedes to Conteh’s 2010 orders

By Monday, April 20, the CCJ had effectively worked with the parties on a consent order. Senior counsel Denys Barrow, representing the Government, said in court that the CCJ order was substantially what the Government had proposed to the CCJ.

In our research, Amandala found the CCJ order to be remarkably similar to the original orders issued by former Chief Justice Conteh back in June 2010, when he first ruled on the case now on appeal at the CCJ. We found one notable difference: that while the Conteh order said that the Government must cease and abstain from actions on the lands in question that would adversely affect the Maya people, unless the Maya give their informed consent, the CCJ order modifies that requirement to say that such actions must be preceded by consultation to obtain their informed consent.

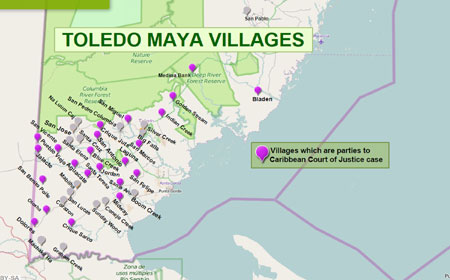

The Maya villages of Toledo

Martin Chen—the head of the Maya Leaders Alliance, who said that he took a bath in the river at 1:00 a.m. to ensure he was ready at the roadside to get on the bus to Belize City at 3:00 a.m.—said that the fight is for every Maya, including those in South Stann Creek.

A total of 23 Maya villages located in the Toledo District were parties to the claim, although there are said to be 38 Maya villages in Toledo and 4 others in Stann Creek, bringing the total number of villages in Southern Belize to 42. The CCJ order is specific only to those villages in Toledo.

How many Maya are in Toledo? The last population census undertaken by the Statistical Institute of Belize says that 66.5% of the inhabitants of Toledo are Maya. That amounts to about 20,000 persons. This is comparable to the estimate provided to us by Pablo Mis of the Maya Leaders Alliance, who says that there are roughly 23,000 Maya in Toledo. This means that an award of damages for $1.5 million would work out to just about $65 per Maya in Toledo.

Furthermore, the Maya are pushing to have about 800 square miles designated as their homeland. The Maya Atlas: The Struggle to Preserve Maya Land in Southern Belize (1997) says that, “The ultimate dream of the Maya is yet to be achieved—the security of tenure to lands and the creation of a 500,000- acre Maya Homeland.”

Amandala has mapped the 38 villages in Toledo, and highlighted the 23 villages which are parties to the CCJ claim. To access the map of the Toledo Maya villages online, please visit this short link: http://tinyurl.com/toledo-maya-villages.

Maya homeland to be secure by 2017?

Apart from accepting the CCJ’s consent order, the Government presented the Maya with a letter of commitment.

Attorney Monica Coc-Magnusson, sister of Cristina Coc, told the Maya gathering that: “This is an additional commitment by the Government of Belize to show that they are serious about your rights and I applaud them for that. I am happy that they came to that recognition and that they have finally admitted like we’ve always been telling them that we do have rights to the land and resources that we live on…”

In the letter of commitment dated Monday, April 20, 2015, Denys Barrow, as counsel for the Government of Belize, wrote saying that, “GOB will promote and protect the collective and individual property rights affirmed in the judgment, and recognizes the exclusive right of each village, subject to law, to control who may take up residence within the villages’ lands.”

He said that the Government will promptly name representatives to meet and consult, to perform and implement its obligations under the judgment.

“GOB will seek to complete the design and model of the mechanism by December 31, 2015,” and would “seek to have that mechanism in place by August 30, 2016,” he wrote. Finally, Government “agrees to work towards demarcation and registration of the Maya villages’ property rights by December 31, 2017…,” he added.

Coc-Magnusson warned that, “This is just the beginning, ‘cause there’s a lot more work that needs to be done.”

A new law for the Maya

Attorney for the Maya, Antoinette Moore, SC, told the Maya this afternoon that, “there will be [land] titles… there will be a law, perhaps it will be called the Maya Land Act, I don’t know, but there will be a law that will be passed by the National Assembly to protect your rights, to ensure that this …order is implemented.”

She said that the Government will work with legal representatives of the Maya to develop a law that will protect their land and rights, but until that happens, the Government has to desist from letting other persons do anything that will affect their land or harm their ability to use and occupy their land.

“The Government has promised to the court and now the court had ordered that Government cannot issue any leases, grants… permits or concessions for resource exploitation unless they have your consent—as owners of the land,” Moore added.

Barrow said that the Government would introduce a new law, perhaps like the Native Titles Act of Australia of 1993.

“These are very firm and solemn commitments made by the Government,” said Barrow, but he added that it is not purely in the hands of the government but it is a question of what is involved in the process. He said that he is advising the Government of the need to undertake nationwide consultations so that the Maya, on a national scale, can say to the people of Belize, this is what they want; and others can say this is what they want and what they think the Maya should get. There has to be a discussion process, he insisted.

The claim for roughly $1.5 million in damages

Since the Government of Belize and the Maya had already agreed to the major points of dispute in the court order finalized this Monday, Wednesday’s court proceedings were focused only on the question of whether the Government of Belize should be made to pay damages to the Maya people.

Attorney for the Maya, Antoinette Moore, SC, contended that the Government had been guilty of perpetrating “egregious violations” against the Maya community – violations which have caused them material losses in lands and crops. For those pecuniary damages, Moore asked the court to award the Maya people BZ$250,000, including $61,000 for damages to crops in Golden Stream after Francis Johnson allegedly bulldozed the crops of two Maya farmers of that village, one of them being Alfonso Cal, chair of the Toledo Alcaldes Association.

She furthermore said that the Maya of Toledo are entitled to broader “moral damages” because of the systemic failure of the Government to respect the customary land rights of the Maya. She said that whereas there were benchmarks for such damages from the courts, there were some awards that had been issued by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. After citing a sampling of those cases, she told the court that the case of the Saramaka people of Suriname was most similar to that of the Toledo Maya. In their case, they were awarded US$600,000 in moral damages, said Moore. She added, however, that the figures presented were only intended to provide references to help the court in making its final determination.

“There is the fact that Belize is not owned now, is not controlled now by descendants of the European invaders and conquerors. I made the point that the Maya are not entitled to damages for deprivation, for oppression any more than Africans [or the other ethnic groups – the East Indians, Garifuna, Mestizo]. Everybody has a claim against the colonial system which we inherited upon independence,” Barrow told reporters.

“Government said, ‘let us give the Maya their wish and put their system of land ownership on a legal, statutory legislative footing,’ but Government should not be made to pay,” he added.

The Golden Stream scenario

Denys Barrow, SC, vigorously opposed both claims for damages. He said, firstly, that there had not been any finding of fact to substantiate the claims by the Maya that the Government had caused the damages claimed.

Barrow dealt extensively with the dispute which arose between Johnson and the Maya of Golden Stream. Incidentally, Johnson—who was murdered in Big Falls in September 2009, the year before the court case concluded in the Supreme Court—was married to a Maya woman, and he had contended in an affidavit to the court that he had gotten the land from his brother-in-law, Salvador Bochub, a Maya, who had gotten the land from Louis Menhevor, who had held a lease going back to around 1970.

Barrow noted that Johnson had stated in his affidavit that he had been working the 50-acre parcel in Golden Stream since the 1980s, mainly farming rice.

However, the attorney noted that one of the farmers who had claimed that Johnson bulldozed his crops gave evidence to the court saying that he arrived in the village in 1991, and Golden Stream was settled in 1985, long after the Government began granting leases for lands that had been unoccupied.

Barrow noted that even former Chief Justice Conteh, in his ruling of 2010, did not find that the Government should be liable to pay damages for the Golden Stream incident, which Moore said was a trigger for the filing of the case which was now in its final round of appeal at the CCJ.

Barrow told the court that such disputes would have to be looked at on a case by case basis, under a proper regime for adjudication, in order to have them resolved.

Competing rights/Cease and desist

During the CCJ hearing, the Government attorney cited statements which had been issued by organizations representing the East Indians and Kriols of Toledo, at the time expressing their rejection of the stance taken by the Maya. Those statements also asserted that other ethnic groups also have rights to lands in Toledo.

Froyla Tsalam, executive director of the Sarstoon Temash Institute for Indigenous Management (SATIIM), said that a lot of people are afraid of what customary land ownership will mean legally, and there are a lot of questions that will need to be answered. She is of the view that the leases issued by the Government after 2008, when the first Maya land rights ruling was issued for the villages of Conejo and Santa Cruz, will be of a different standing than those issued in the pre-Independence era of the 70’s and 80’s, for example. However, she remains hopeful that a system can be worked out that will respect the rights of all parties, Maya as well as non-Maya living in the area. She called the developments this week at the CCJ “a step in the right direction.”

We got no clarity today on what the ruling will mean for existing lease and contract holders in Toledo, in areas deemed to be Maya lands by those communities. Moore told us that the consent order, as she interprets it, means that the Government should now come to the table with the Maya leadership on existing permits and concessions. Barrow said that the Government will have to consult with the affected Maya communities before deciding whether it will renew the expiring permit to US Capital Energy to continue exploration inside the Sarstoon-Temash National Park in Toledo.

Moore told the Maya villages that the CCJ order requires that the Government must first consult and obtain the informed consent of the communities before they are able to take certain actions. She said that while there are questions about what constitutes consent and consultation, there are international standards already set. She said that very recently, the Maya leadership presented a draft consultation framework to the Prime Minister and other persons in government, and this document, she says, sets out the protocol for consulting with the Maya community so there is no confusion.

The Petroleum Act requires that the Government gets consent from any landowner—not just the Maya—if they intend to enter or drill upon private lands, and the law also says that the landowner cannot withhold consent without a good cause or reason.

Pursuing unity among the Toledo Maya

Coc said that “…because times are changing, we will wait to see how our children continue to write history. I am hopeful but I am saddened, because some of our brothers are still lost…”

“We have some little group on the side there that don’t like us. They don’t understand what we are struggling for. But like Mr. Cal said, we are fighting the cause for them also,” said Chen.

“There are still some of our brothers and sisters who are still in prison, because they do not yet understand – they do not yet grasp the magnitude of the struggle that you all have carried and it is now our duty, our responsibility collectively to bring them to that higher understanding – to bring them to that realization that we will not achieve unless we are united as a people That the dream is not just for our children but the children of their children… and none will be denied the enjoyment of the rights that were affirmed today in the Caribbean Court of Justice…” Coc also asserted.

The order of the CCJ

The CCJ order stipulates the following:

1. The judgment of the Court of Appeal of Belize is affirmed insofar as it holds that Maya customary land tenure exists in the Maya villages in the Toledo District and gives rise to collective and individual property rights within the meaning of sections 3(d) and 17 of the Belize Constitution.

2. The Court accepts the undertaking of the Government to adopt affirmative measures to identify and protect the rights of the Appellants arising from Maya customary tenure, in conformity with the constitutional protection of property and non-discrimination in sections 3, 3(d), 16 and 17 of the Belize Constitution.

3. In order to achieve the objective of paragraph 2, the Court accepts the undertaking of the Government to, in consultation with the Maya people or their representatives, develop the legislative, administrative and/or other measures necessary to create an effective mechanism to identify and protect the property and other rights arising from Maya customary land tenure, in accordance with Maya customary laws and land tenure practices.

4. The Court accepts the undertaking of the Government that, until such time as the measures in paragraph 2 are achieved, it shall cease and abstain from any acts, whether by the agents of the government itself or third parties acting with its leave, acquiescence or tolerance, that might adversely affect the value, use or enjoyment of the lands that are used and occupied by the Maya villages, unless such acts are preceded by consultation with them in order to obtain their informed consent, and are in conformity with their hereby recognized property rights and the safeguards of the Belize Constitution.

This undertaking includes, but is not limited to, abstaining from: (a) issuing any leases or grants to lands or resources under the National Lands Act or any other Act; (b) registering any interest in land; (c) issuing or renewing any authorizations for resource exploitation, including concessions, permits or contracts authorizing logging, prospecting or exploration, mining or similar activity under the Forests Act, the Mines and Minerals Act, the Petroleum Act, or any other Act.

5. The constitutional authority of the Government over all lands in Belize is not affected by this order.

6. The Court shall determine the remaining issue in this case, namely the Appellants’ claim for damages.

7. There shall be liberty to apply.

8. The Appellants’ costs of this appeal and in the courts below shall be agreed by 30th April 2015 or taxed.

9. The Court retains jurisdiction to oversee compliance with this order and sets 30th April 2016 for reporting by the parties.