A LETTER FROM STEVE BIKO

Some of you, my people,

you weep and you mourn.

“Poor Steve Biko,” you say,

“he beaten and was died,

so young, so strong.”

It’s true, I beaten and was died

because I dare to speak

for black and brown,

but poor? No, a thousand times

NO!

I stand and fight.

Yes, also I was destroyed,

but not defeated.

For my sweat waters the soil;

my body and my blood

add richness to the earth.

And from the earth and soil

a thousand children spring.

They cry across the hills

and over the smoky rivers

of wherever rest my bones:

Steve, Steve Biko, they cry,

Steve Biko die,

that we may live.

(by Evan X Hyde, 1977)

In the British and French Caribbean, the slave societies were different from the slave society in the United States of America, in that there were discernible and distinct mulatto classes in the British and French Caribbean. In the U.S., there are mulatto families in places like New Orleans and parts of South Carolina who have a history going back generations which features some sort of privilege, or difference from American slave society, but overall, there is no discernible and distinct mulatto class in America. Black was black, across the board. If you had a single drop of African blood in America, that made you black, and therefore eligible, by Supreme Court decision, to be a slave.

They say behind every cloud there is a silver lining, and the race policy in America forced black Americans to become more monolithic in their unity, whereas in the British and French Caribbean, blacks and browns were separate classes which became hostile to each other, and in the case of Haiti, they waged war against each other.

My younger brother who lives in Arizona did some DNA testing the other day, and he came up 47% African and 42% European, 7% Native American and a few minorities. This is what we call “mulatto” today, but it is, more precisely, mixed ancestry. Originally, a mulatto was the child of a white father and a black mother – half and half.

Belize was a cute little place when I was growing up. The society was more based on color than on race, because the races were already so mixed. In addition, there was a lot of ignorance where race classification was concerned. Above all else, everybody was scared of being called “African,” or “Zulu,” so even people who were very dark-skinned would never allow themselves to be referred to as “African.”

If you read Sports, Sin and Subversion, you will realize that as a child of maybe 9 or 10, I was attracted to the style of young men who were black Belizeans as represented by the Dunlop football team. At the same time, in basketball and in cricket, I had mulatto heroes, and our older family friends were mostly of that class.

When I landed on the Dartmouth College campus one evening in September of 1965, I met a small incoming group of foreign students the following morning. We were there for special orientation one week before the arrival of the American freshmen who would be the Class of 1969. There were two African students in this group of foreign students – Saleh Jibril from Nigeria and Guy Mhone from Malawi. I thought Mhone was a Jamaican, because he dressed so stylishly. I was 18, Mhone was 22, and I think Saleh, who was strict and sober, may have been a couple years older. (Jibril afterwards became a banker in Nigeria.)

Mhone and I quickly became friends, but we lived in separate dormitories – he in Cutter Hall, which was considered an exotic residence with most of the foreign students and those American students who were more cosmopolitan in their life experiences and their thinking, and I on the second floor of Bissell Hall, which was almost all regular American students.

On a day-to-day basis, I interacted more with a white freshman from Wisconsin by the name of Steve Cline, than with Mhone. Cline lived across the corridor from me in Bissell. We were such good friends that I visited his family and home during the spring break of 1966. Cline and I “rushed” and joined the same fraternity, Zeta Psi, in the fall term of 1966, but in the winter term of 1967, the controversial visit of segregationist Alabama governor and Democratic presidential candidate, George C. Wallace, sparked a rowdy demonstration by Afro-American students at Dartmouth. This is when I began becoming more black–conscious, I began drinking even more, and Cline and I drifted apart.

Early in the winter of ’67, my dad had informed me that he and my maternal grandaunt, Gladys Lindo Ysaguirre, were buying a plane ticket for me to visit home in the summer of ’67, my first trip home in two years. Three weeks before I flew home, I broke my right tibia playing inter-fraternity football, and spent the whole summer in Belize on crutches with my right leg in a cast from hip to toe.

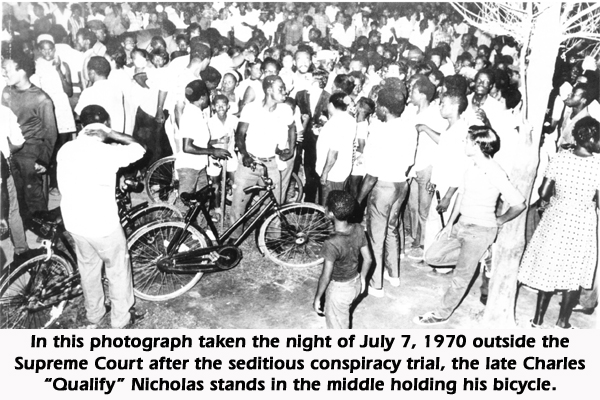

I’d invited Guy to spend the summer in Belize as my family’s guest, and he managed to reach here a week or so after I arrived home, after the airlines had sent him to the republic of Honduras. My dad had gotten Mhone, an economist, a summer job in Premier Price’s Ministry of Finance, and my job was at the Regent Street law firm of W. H. Courtenay & Co. After work, Guy and I did a lot of drinking, and we often ended up in the wee hours of the morning at Pancho’s – Nacho Coye’s restaurant /club on Regent Street West. There we frequently conversed with Serapio “Big Mole” Alvarez and Charles “Qualify” Nicholas. These were young, dark-skinned Belizeans from Mugger Garbutt’s Independence football team, and I am wiling to wager that Mhone must have been the first real African they had ever met.

When we flew back to the States, Mhone stopped to spend the ’67 fall term at an Alabama university. When he came back to Dartmouth for the winter and spring terms at Dartmouth, our last two in New Hampshire, we became even closer, because he would cook meals on a hot plate in his dormitory room. This was against college regulations, but for sure Mhone’s meals were ten times better than the stuff they served in the college cafeteria.

Both Mhone and I graduated in three years instead of four, because Dartmouth accepted our Sixth Form credits. Malawi had been a British colony in southern African called “Nyasaland.” They had the same “O” Level/”A” Level education system which British Honduras did. But Guy Mhone, as cool and cordial a brother as you’d ever want to meet, at some point had become involved in rebellious student politics in Malawi. The problem was South Africa, which was hard-core apartheid in those days of the mid-1960s.

White, apartheid South Africa was by far the largest and richest economy in southern Africa, and Malawi’s strongman leader, Hastings Kamuzu Banda, for personal advantage had decided to work along with apartheid Johannesburg. Banda was betraying African people. The students of Malawi, and it is clear that the brilliant Guy Mhone was a prominent student voice, were informed about incidents such as the horrific Sharpeville massacre in 1960 and the jailing of Nelson Mandela in 1964, and they had been inspired and inflamed by the music of exiled South Africans like the trumpeter Hugo Masekela and the singer Miriam Makeba.

Guy Mhone became estranged from his father, a Banda supporter, and barely managed to escape from Malawi and reach Dartmouth. As we graduated in June of 1968, I was headed home, and Mhone remained a student exile in America. Going home to Malawi would have meant beatings and jail. Guy Mhone went to graduate school – the University of Syracuse, from which he obtained his economics doctorate.

By the late 1970s, when Mhone was teaching in the United States, we had basically lost contact, but around 1985 or 1986, my cousin, Margie Fairweather Laing, to whom I’d introduced Guy in the summer of 1967 in Belize, told me that she’d met him at a cocktail party hosted by the Zimbabwean embassy in Washington. Zimbabwe had originally been white-ruled Rhodesia, apartheid South Africa’s leading ally in southern Africa. Robert Mugabe became Zimbabwe’s black leader at the time of independence in 1980 after years of armed struggle. Guy Mhone would have been welcomed inside the Zimbabwe fold, because Mhone was a world-class development economist.

I finally made contact with Mhone in the mid-1990’s after almost two decades without direct communication. He was teaching at a university in Johannesburg. Telephone rates were excessive, and so our conversation was too brief. I remember he said he had feared I would be killed in Belize.

About nine years ago, Guy Mhone died during an operation for appendicitis. I had just re-established contact with him in order for him to be interviewed for UBAD research being done by the University of Belize’s Dr. Joseph Iyo. Guy and his wife, Yvonne, had two children – a son and a daughter.

Guy Mhone taught me about jazz music and the traditional pride of Africans, among other things. I never felt like a mulatto with him, just a younger brother who was seeking to learn about his ancestors and his reality. There are many mulattos in Belize who are very confused people: they never had a Guy Mhone to teach them.

As we celebrate the life and mourn the passing of Madiba, let us not forget all the other South African leaders who were imprisoned with him and all the suffering of the South African people under apartheid and the various racist protocols which preceded it. For myself, on the occasion of Nelson Mandela’s death, I remember Guy Christopher Zimema Mhone, because he was one of those Africans who took a principled stand because of their support for Mandela and the struggle against apartheid. Because of that stand, Guy Mhone spent many years in lonely exile from his home. Guy Mhone suffered in the struggle. Guy Mhone was one of those who took the stand and paid the price. I honor him.