There’s an important article on the Caste War in this Tuesday’s edition of Amandala, but it is a fairly long article and I’m sure most of you won’t take the time to read it. The reason the article is important is because it was written by a former British High Commissioner to Belize, Mr. Peter Thomson, and because it is the first admission I know of, in 2004, by a British official that the British and the Santa Cruz Maya had a “rapprochement” in the second half of the nineteenth century, at the same time that the “Mexicans” had a similar relationship with the Santa Cruz Indians’ “most significant rival Indian tribe, the Icaiche (or Chichuanha).” In other words, it was Belize and the Santa Cruz Maya (the bravos) versus Mexico and the Icaiche (the pacíficos) at various times during the 1850s.

The quotation marks around “Mexicans” are mine because in 1853, when the Mexicans and the Icaiche cut a deal, Mexico was not the modern nation-state we know today. The Yucatán had always been somewhat of a self-contained entity, because it was so distant from the federal capital in those days. Transportation was probably faster by sailing ship than by road 150 years ago, and if you look at the map you will see that Texas is actually much closer to the Yucatán than Mexico City is. There is a history between the Yucatecans and the Texans, who were both giving the federal Mexican authorities all kinds of trouble from time to time.

Before its independence in 1821, Mexico was known as “New Spain,” and its territory included both the Yucatán and Texas. A couple decades after Mexican independence, there were Sam Houston and Davy Crockett and Santa Anna and the Alamo, and Texas became a part of the United States of America.

Anyway, when Thomson referred to “Mexicans” on page 91 of his book, Belize: A Concise History, he was referring to Mérida and Campeche. I can’t see it any other way.

Before I proceed, let me say this. There is a scholar in Belize who is an expert on the Caste War. His name is Dr. Angel Cal, but he never, ever participates in any kind of public discourse on that conflict which is so historically relevant to the history of Belize. The reason Cal never engages in public discourse in his area of expertise, I submit, is because he is a professional academic, and he is concerned about his career in Belize, this being a country where academics are intimidated by politicians.

Belize is not Jamaica, and Belize is not Barbados. Belize is not the British Caribbean. The reason this is so, apart from the fact that Belize was the only British possession in Central America, is because of the Caste War. This was a war which was buried in history because such a burial suited the interests of the Yucatecans north of us and the British here in Belize. But such a burial in history of the Caste War is definitely not in the best interests of the new nation-state of Belize.

By the way, in this issue of Amandala there is another long article on the Caste War, even longer than Tuesday’s. This one is taken from Don E. Dumond’s epic The Machete and The Cross, published in 1997. I urge you to read it. The excerpt from Professor Dumond’s book covers a period of conflict between the British and the Santa Cruz Maya between 1860 and 1861. There was no real border between British Honduras and the Yucatán in 1860 and 1861. Mahogany contractors from Belize had been encroaching on Mexican territory to cut and extract hardwoods. When the Caste War broke out in 1847, the Santa Cruz Maya, followed by the Icaiche, began to “tax” these contractors. The extortions involved violence, and the British, according to Dumond, “felt themselves powerless to take effective action.”

Since, it appears to me, the history has recently emerged in these parts that Belize settlers arranged for London to make Belize a British colony in 1862 because the Belize settlers had gone broke, it suggests to me a reason why in Belize we never used to hear a thing about the second half of the nineteenth century here, except for the beginning of “Centenary” in 1898. The reason is that the Maya, who were not supposed to exist, were kicking a—in the north and the west, and the Brits couldn’t do much about it.

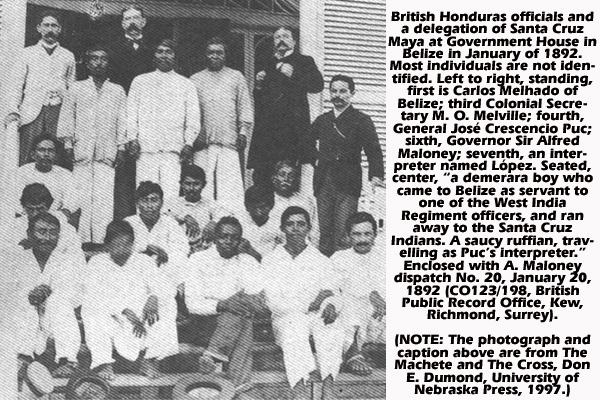

In 1892, a delegation of Santa Cruz Maya visited the British Governor, one Sir Alfred Maloney, at Government House in Belize. The Santa Cruz leader was General José Crescencio Puc, and he brought with him a black man as his interpreter. In his dispatch, Governor Maloney refers to this black man, seated in the middle of the front row with his legs crossed in the accompanying photograph from Dumond’s book, as “a saucy ruffian.” The caption describes the black man as “a demerara boy” who came to Belize as a servant to one of the West Indian Regiment officers and ran away to the Santa Cruz Indians.

The photograph intrigues me at the same time that it frustrates me. From his exaggerated pose, you can see that Governor Maloney was a pompous British official who would have had a problem with a liberated black man. Personally, I would have liked to meet the “saucy ruffian.” More than that, I would have liked for him to have had an encounter with Simon Lamb. I am betting that in Noh Cah Santa Cruz, “demerara boy” would have been like royalty. And in Belize, he would not have taken any disrespect from Maloney or any of his people.

The frustration derives from the fact that we don’t know anything else about this brother. Running north to freedom in the Yucatán was a journey black men in Belize had been taking from slavery days in the settlement. The classic such journey was in 1773, when 19 slave rebels from the Belize Old River, out of an original total of 50, reached Bacalar.

Once a black man from Belize reached the Yucatán, the important thing was for him to accept the Catholic religion. Once he did so, the chances are he would end up marrying a Maya or a Mestizo lady. His children, their children, and all his generations down the line, would be considered full-fledged Mexican citizens, and their ancestral origins in Baymen Belize would be forgotten, except perhaps in family anecdotes.

There are black Belizeans here who are Anglophiles: they are British in their behavior and thinking. I understand why. I am not one of those. I am African in my thinking, and I know why. I give maximum respect to the Santa Cruz Maya.

Power to the people. Power in the struggle.