Photo: The mangrove-covered area that is the proposed location of the Port of Magical Belize cruise ship port. (Photo by Marco Lopez)

The untapped potential for generating revenue through climate-based solutions via the blue economy is at risk of being lost if a sustainable equilibrium is not found with the tourism development boom in Belize.

by Marco A. Lopez

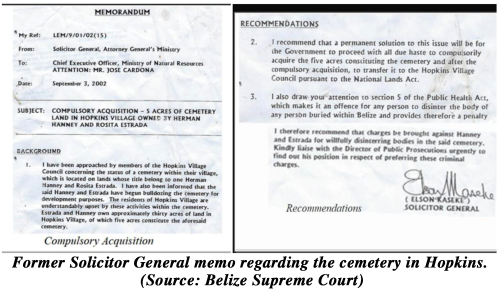

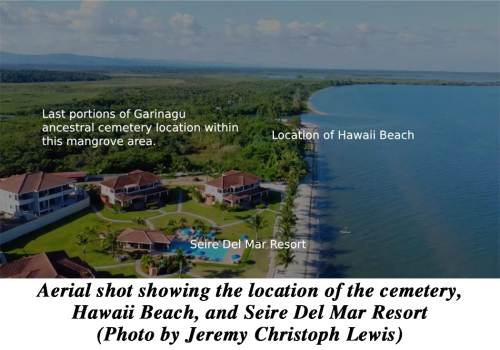

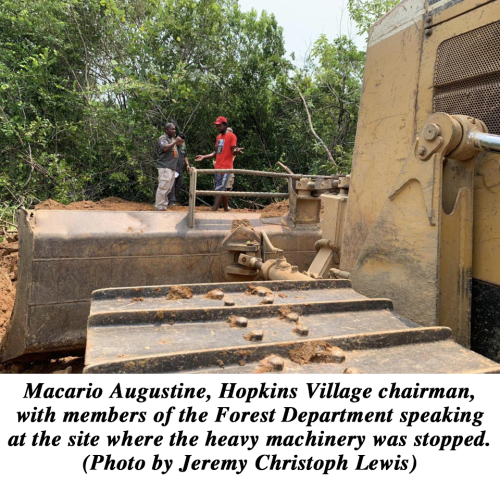

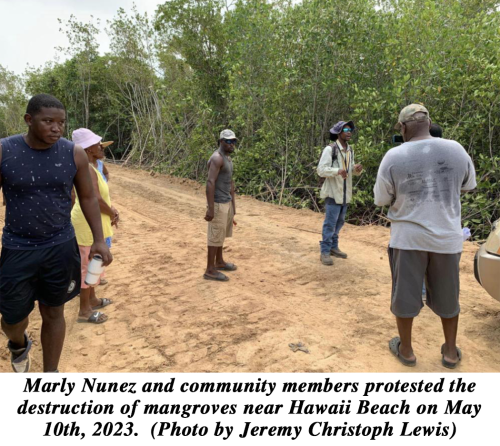

On May 12, 2023, the Forest Department of Belize issued a stop order to prevent the unauthorized destruction of mangroves on the coast of Hopkins Village. A developer has privatized communal lands used by villagers from “time immemorial”—an area they called Hawaii Beach. The location, covered by mangroves and coastal forests, is the last remaining part of a Garinagu ancestral cemetery. In 2002, former Solicitor General, the late Elson Kaseke recommended that the Government of Belize acquire the area and create a memorial of 5 acres. These recommendations were never followed.

Two other resorts – Seiri Del Mar and Hopkins Bay—were both constructed on portions of the burial ground. Acres of mangroves were destroyed, and with it, the burial ground of the Garinagu ancestors as well as children, and the financial benefit those coastal ecosystems could have provided to Hopkins.

Marley Nunez, a community leader, hopes to never see the destruction of his loved ones’ final resting place occur again. Along with the village chairman, Macario Augustine, and a group of community members, they have rallied ardently against the destruction of the last portion of the burial ground – the mangrove and wetland ecosystem that supports subsistence fishing in the community—and the privatization of the beach used by villagers for recreation.

“The area is used seasonally as a fishing ground for locals,” Nunez shared, pointing to the dense patch of mangrove adjacent to the coastline. “We have never stopped using this place. Inside there is the first Hopkins cemetery, and we have always thought that it would have been left untouched,” Nunez expressed.

In January, the Belize Tourism Board (BTB) in a press release forecasted new records in arrivals in 2023. Most travelers come from the United States and Europe, our two largest tourism markets, according to BTB. The need to expand infrastructure to cater to the increased number of visitors goes without saying: the tourism industry is the largest economic earner in the country. According to the International Monetary Fund Working Paper, “Tourism in Belize: Ensuring Sustained Growth,” the sector contributes a total of 40% of GDP. As a result, developers have proposed several projects to accommodate the projected increase in cruise and overnight visitors countrywide.

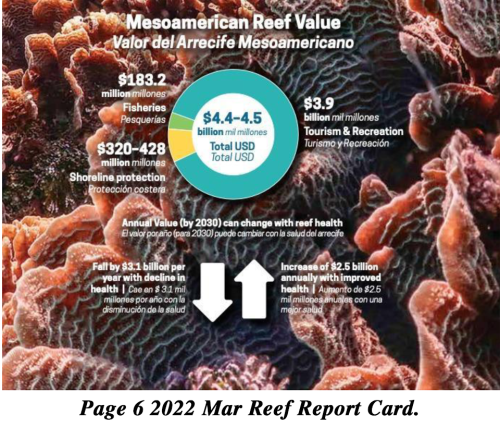

With the Mesoamerican Reef System (MAR), the largest Barrier Reef in the Atlantic Ocean hugging the coast, the Belizean blue is the lifeblood of coastal communities like Hopkins. According to the Mesoamerican Reef Report Card 2022 by Healthy Reefs for Healthy People Initiative, the MAR contributes approximately $4.4 billion – $4.5 billion to the four countries whose coasts it touches.

According to a 2009 study by the World Research Institute and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), mangroves and coral reefs play a significant role in Belize’s economy. They fuel the tourism sector, contributing around US$173 million annually, which makes up about 13.5% of the country’s GDP. These ecosystems are integral to the local fishing industry, providing around US$15 million in economic benefits each year. Additionally, they function as natural shields for the coast, saving approximately US$289 million per year in costs resulting from possible damage.

However, many of the new proposals for tourism infrastructure are in coastal marine environments that house priceless coral reefs and associated ecosystems: mangrove forests and seagrass beds. These three ecosystems together sustain each other. A 2021 study entitled, “Synergistic benefit of conserving land-sea ecosystems” states, “Mangroves and seagrasses serve as nurseries and shelter for reef fish, and all three habitats participate in biogeochemical and trophic exchange facilitated by migratory coastal organisms. In addition, mangroves and seagrasses regulate sediment discharge from the land, mitigating extreme sediment flows that may otherwise smother corals.”

Despite the above, in Belize 70% of the coast where these ecosystems are located is already privately owned; as in the case of Hopkins, communities are often stripped of their birthright—with no consultation—to facilitate these developments. In Belize, corruption, as in the sale of lands designated for a memorial, and many other types of scandals, oftentimes accompany these developments. Access to the beach and vital fishing grounds is restricted, and ecosystems are irreversibly damaged. Ways of life cultivated for generations are destroyed in the blink of an eye.

In a developing country like Belize, whose economy is dependent on the tourism industry, deep-pocketed individuals often circumvent key environmental rules. However, an example of effective law enforcement is the case of Hawaii Beach in Hopkins, where the destruction of mangroves was stopped on May 10, 2023, because the developer lacked the requisite permit.

A study published on June 1, 2023, cites Hopkins Village as one of the priority areas for mangrove protection and restoration.

“We realize the investors are trying to claim Hawaii or take away Hawaii from us. They are really getting destructive. We take it seriously, and decided that we will put a stop to it,” Nunez said while we spoke on Hawaii Beach. For the past three months, they have been actively monitoring the developments and confronting proponents when needed to prevent the cordoning off of the area.

But in many other communities, these developments are unprotested and are executed without any consultations with, or input from, the community members.

Assessing Proposed Developments’ Impact on the Blue Economy

We looked at five tourism developments that have been proposed but are not yet operational in Belize. Data from the developers’ Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) were used to determine the proposed impact on mangrove and seagrass ecosystems as a result of dredging for each project.

We focused on how much of an impact these activities could have on the blue economy, and Belize’s goals to attract revenue from blue carbon. But first, what do the “blue economy” and “blue carbon” mean for Belize?

The blue economy is defined by the United Nations, “as an economy that comprises a range of economic sectors and related policies that together determine whether the use of ocean resources is sustainable.”

A study published by Nature suggests, “the blue economy intends to be economically viable (prosperous) and environmentally sustainable, but also culturally appropriate and focused on social equity and well-being.”

In Belize, the current government formed a Ministry of the Blue Economy and has drafted a policy to “set out an enabling framework for blue economy development.” But a lack of coordination across government departments is a major shortfall in ensuring sustainable development along the coast of Belize, WWF country representative Nadia Bood explains. She points out, for example, how four policy documents – the Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan, the Environmental Protection Act, the Environmental Impact Assessment, and the Mangrove Regulations—are implemented by different agencies, and points out, “I don’t think there is much strong coordination among these departments to allow for more effective implementation and enforcement of these policies.”

Bood, who is the Senior Program Officer at WWF in Belize, explains, “You have all these duplications of enforcement, of organizations that should be implementing these policies, and I don’t think that they speak much to each other. In terms of the coastal zone, I know that they have a Coastal Advisory Committee that includes some of these entities.”

She added, however, “But we are not seeing the effects of that on the ground. For example, we continue to see significant clearance of mangroves, up to the waterline; we see dredging happening and we see erosion happening. So, there is a disconnect in terms of the coordination – the strong coordination to allow a more sustainable approach to the management of these ecosystems.”

(Continued from page 28 of Amandala for Friday, June 23, 2023)

Belize’s Blue Carbon Strategy

Like fisheries, eco-tourism, and coastal protection, blue carbon is a resource available within the blue economy. It is defined as carbon sequestered and stored long-term by the ocean – and in coastal ecosystems such as mangroves and seagrass beds. It is another viable sustainable marine resource that countries can explore, and is now being viewed globally as a valuable currency.

According to NOAA’s Office for Coastal Management, the aforementioned ecosystems (seagrasses and mangroves) are also recognized as significant contributors to climate change mitigation since they remove carbon from the atmosphere at rates that surpass other carbon capture environments such as tropical forests.

Belize’s 2021 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) cites an increase in mangrove and seagrass protection to tap into this blue carbon market to achieve its national low-emission development goals. Despite this, seagrass remains unprotected in Belize, and mangrove forests are still being destroyed for development. While the Forest Department mandates permits, many developers tend to disregard those regulations, as seen in the attempt in Hopkins.

Also, the country signed on to a Blue Bond in November 2021 which reduced the debt burden by restructuring a huge portion of the national debt. A total of 180 million dollars is to be generated for marine protection and in exchange, Belize has committed to protecting 30% of its ocean by 2026.

The country’s future is tied to having a strong and healthy marine environment, so safeguarding these ecosystems is pivotal. However, at present, those blue carbon sinks are at risk of being lost in Hopkins and across the country due to unsustainable tourism infrastructure development.

What is the blue carbon sequestration potential of Belize and why should marine ecosystems be protected?

According to a recently published study entitled “Belize Blue Carbon: Establishing a national carbon stock estimate for mangrove ecosystems”, authors Hannah K. Morrissette et. al., explain that mangroves, seagrasses, and tidal marshes, are prime examples of blue carbon ecosystems with “mangroves alone being 4–5 times more effective at sequestering carbon than tropical terrestrial forests.”

The study also provided the first comprehensive estimate of the total carbon stock in Belize’s mangroves, which is approximately 25.7 tera-grams of carbon (TG C). This data highlights the significant carbon storage capacity of Belize’s mangrove ecosystems. Nadia Bood, a co-author of this study, explained how this data helps with understanding what carbon stocks exist in Belize.

“If we understand what carbon stock exists within the ecosystem, from international carbon credit agencies, we can understand how much you can get in terms of economic generation per hectare,” Bood explained.

The next step is to determine the value of these ecosystems. Fieldwork was conducted at Hicks Caye, Drowned Caye Range, Shipstern Lagoon, New River, Gra Gra Lagoon, Channel Caye, Big Creek, Payne’s Caye, Frenchman Caye, and Turneffe Atoll.

Seagrass, according to the WWF, is said to be 35 times more effective at capturing carbon than tropical rainforests.

The Seagrass Conservation and Protection in Belize guidelines note, “the capacity of Belize’s seagrass stock to sequester and store carbon represents a potentially major benefit in terms of the nation’s carbon budget, but insufficient data currently exist by which to assess this.” Both mangrove and seagrass ecosystems play a vital role as carbon sinks. In addition, they protect from storm surges, create a nursery habitat for juvenile fish, and help prevent erosion, the document specifies.

The destruction of these ecosystems not only results in the loss of carbon storage capacity but also releases stored carbon back into the atmosphere, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

On-the-ground

“Unfortunately for Belize, there is a great demand for coastal development,” Bood said. “People want to live along the coast, the hotels and resorts tend to exist along the coast and the cayes, and so with the construction of these kinds of structures, it leads to deforestation,” she added.

Bood emphasized that 70 percent of the coast, where these blue carbon sinks are located, is currently owned privately.

“When that happens, it [coastal development] affects the other blue carbon ecosystem, the seagrass beds, because the sediments smother the seagrass beds and reduce light penetration that these vegetation needs to survive,” Bood said. She shared that development within these environments has had a significant impact on the blue carbon sinks in Belize. This additionally has an impact on the blue carbon credits that can be derived from the carbon sequestered by those ecosystems.

To be continued…

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.