A cool summer breeze blows off the sea near the Yarborough area, which is inhabited by a quiet Belizean community in Belize City and overlooks Albert Street and the image of a haunting colonial graveyard that is a reminder of a colonial slave society. The statue of Isaiah Morter, the Afro-Belizean millionaire and philanthropist who once owned Caye Chapel and was a member of Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), hails the passersby. And the area also known as Ibo Town that marked the first landing of African Igbo slaves, calls out to its descendants, now known as Kriols, to rise to their destiny. But there is a deafening silence as young black Belizean men mingle about, deeply involved in their own business, as though they never knew from whence they came.

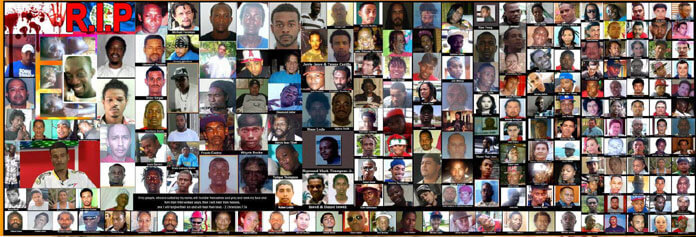

My returning back to live in that same area many years after my migration from Belize allows me to struggle with the changing dynamics of a Belizean society that was a community in the true sense of the word. The humid, hot air blows out memories of a past that has long gone, and what had appeared to be the sound of silence, has erupted time and time again into gruesome gun violence. Yet my mind recollects and ruminates, then tries to generate solutions through brainstorming as I read about Belize’s suddenly acute crime problem that has become a reality staring me in the face. It was like the images of violence on the front page of the Amandala newspaper had suddenly jumped out into my face in the form of an insulting wake-up call that disturbed the life force in me. There were images in its print of the black faces of those who have become the menace to our nation, doing the killing as well as being killed. The time had come for me to be a witness to this rather than just a distant drum of criticism — to attest that the children who were supposed to be a country’s promise had become engulfed in a destructive abyss of self-hate, anger, and displaced frustration.

People go by everyday with their lives, as though they are hypnotized to disbelieve that the present is really happening — until the crime comes to their doors and someone’s loved one cries out in pain and distress after being robbed of peace and happiness. Seeing this violence unfold before my very eyes once and then twice was enough to make me realize that something is seriously wrong in a society of rich and poor, haves and have-nots. How can young black men dressed in ski masks, who had recently earned a high school diploma, suddenly rob and murder in cold blood someone of their own kind for money that they did not earn or work for?

These were the kinds of questions that baffled me upon my seeing the first act of violence that was inflicted upon another right in front of the historic colonial cathedral, St. Johns Church, that was built by the ancestors of those same black men who were committing black-on-black crimes and being stereotyped as criminals in Belizean society. I pushed myself into the scene of the crime to witness what my soul struggled for decades to understand when I lived abroad: It is not an easy thing to watch the blood and brain tissue of a human being flowing like discarded matter through the water of the drain into which he had fallen to his death.

It is a scene that only those who have known the ugly ravages of war can attest to as witnesses. But the people’s faces running to the scene were immediately contorted by the sight of the lifeless body; their eyes glared in horror as they sighed and groaned in despair at the trauma that they were witnessing. By looking at their faces, one could detect pain in their hearts, as well as a paralyzing remorse and sadness stirred by the crime of which they became witnesses. Across the city this has become a traumatic source of oppression upon the people, particularly children who have had to grow up in these predatory and violent environments. Whether they had a choice or not, they appeared to be forced to live in it for the lack of betterment and opportunities to escape the decadent turn of events in Belizean culture.

Weeks later, a dear friend of mine who was a mechanic became entangled in a confrontation with young black men stealing mangoes in the heat of another morning that started out being so beautiful and peaceful. The commotion in front of my gate alerted me to step out of my daily morning comfort zone to observe what had appeared to be a disagreement and a face-off between him and two youths from the nearby neighborhood. Trying to be the peacemaker in the standoff between two angry black young men and a grown black man, my thoughts suggested that perhaps my speaking with some reason, peace and respect to the youthful teenagers would somehow stop their aggressive approach towards the elder of their kind.

But at first the two youths weren’t having it and hastened their march forward. So the man in me yelled out to the single and bold attacker to stop and look up at me on my verandah, which he did. He then threw his piece of weapon on the ground, and turned back to leave. But as he did so, he verbally warned his elderly enemy that they would be back, and come back they did, and murdered him.

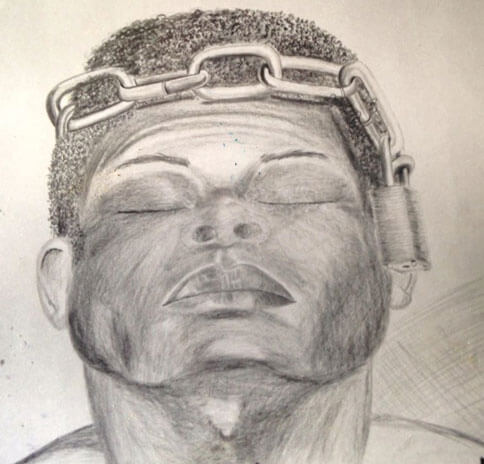

The shock and trauma that was stirred in me by that warning which my friend received to be careful and to heed their words is as clear to me today as it has ever been. Maybe not leaving him so vulnerable as a victim of retaliation could have saved his life. But the unbelievable thoughts that had haunted me about whether a nation that had birthed me had actually gone this way were weighing heavily on me, and forcing me to face the cold realities. It bothered me that these young Belizean black men in Belize who were committing these murders were being possessed by something greater than just anger and self-hate. It appeared to me that they were reacting to the social, economic and political conditions that have been threatening their survival and polluting their existence and destiny.

It appeared that they are striking out at something that they cannot hold with their hands, and as a result they instead aim their aggression at anyone who resists their attempts to take that which does not belong to them. This became apparent to me after catching a few of them stealing mangoes in my own yard, so rather than punishing them for it, some kind of sense in me pushed me to ask them what they would do with the four bags of mangoes that they had already accumulated from the tree in my yard. Their reply was that they sell them to the Spanish people on Albert Street for $40 a bag. These were teenagers who were out of school for the summer, and realizing that there were absolutely no jobs for them in the long, hot summer months, they resorted to stealing, robbing and conniving to make money.

We have to be socially conscious of the present conditions that affect societies like Belize if we are to show any kind of understanding when in confrontations with young people who are being marginalized and disenfranchised in society. It is not an apology for them, but rather a means to avoid conflict that can become destructive and devoid of any kind of amicable peace or solution to the problem. So my releasing them from my yard with the advice to ask for the mangoes rather than trespassing and stealing them made me some friends rather than enemies. They returned weeks later and asked my permission to have the mangoes that were so plentiful and impossible for my family to consume. One prisoner at the Belize Central Prison in Hattieville once told me while I was doing visitations and Islamic work there that there are some young men in jail who do not even know how to ask for something. Rather than asking for it, they just grab it out of your hand and say, “Gimme mines!”

It also became obvious to me that these young black men who are allegedly committing all these so-called crimes in Belize City and Belize proper for that matter, do not really understand what being black means in a society that has failed to provide proper means and solutions for them to escape poverty. It had also become clear to me that they don’t even know why they are poor and how their families cannot escape the scourge of poverty. It also became understood to me after witnessing the senseless murder of my friend at the hands of one of these young black men over pathetic foolishness that Belizean society has failed to understand why these young men have become gangsters.

It appears to me that they see the gang as their friends and family — more so than even their parents who curse at them that they are no good and worth nothing, and who are thus sometimes seen as their enemy. But the underlying Belizean society that shuns and discards them, as an enemy and menace to society, must understand that poverty in Belize has created monsters out of their own children. And I also understand why these Belizean black men have the highest dropout rate in our educational system and are prone to commit crimes. As the Honorable Marcus Garvey had said in his memorable speeches trying to resurrect the lost and found nation of black people around the world, “Who wants to be poor, to be poor is a hellish state!” Belizean society will have to look itself in the eye someday and face the truth that it has failed its children.

(Photos & artwork through the courtesy of Belizean artists Rudolf Bent, Erwin Muhammad & yours truly)