Young Jim Waight was full of excitement and anticipation. The year was 1933. Work was about to commence on the actual opening of the border line between British Honduras (now Belize) and Guatemala. The young surveyor was a member of the team charged with this job. He saw this as an opportunity to further prove himself. Waight was the first British Honduran (Belizean) to be admitted to the Surveyor Apprenticeship Programme. Up to that point he had received all his training in-country. Theory was taught at St. John’s College, then located at Loyola Park in the Yarborough area of Belize City. Practical training was done by attachments to qualified surveyors in the field.

When, a few years earlier, the Guatemalans indicated that they were amenable to the demarcation of a boundary between the two territories, the British Directorate of Overseas Surveys was not very enthusiastic. They claimed that they were already fully committed elsewhere (compartmenting the British African holdings after World War I.) They had neither the qualified surveyors nor the financial resources to spare. For a while it seemed that this opportunity to take a giant step towards the resolution of the long-standing British/Guatemalan dispute would slip away. Then the cavalry came to the rescue, so to speak. The British Honduras Survey Department, headed by F. W. Brunton, an Englishman, claimed that they could do the job with the local staff. The British did not share this view. They were very sceptical about the ability of the local staff (both native and expatriate) to undertake this important and demanding task of such magnitude. The British Honduras Survey Department, however, was persistent in its claim, and, in fact, pleaded that they be given the chance to do the job. The British hemmed and hawed while subjecting the local staff to intense technical and professional quizzing. Finally they reluctantly and grudgingly gave the green light. Quite likely they had their fingers crossed and probably were privately hoping that these colonial upstarts would fall flat on their faces over this job.

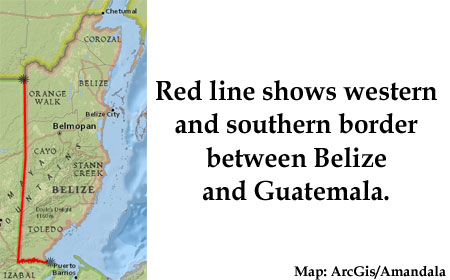

Once the decision was made, things began to happen. A British Honduras/Guatemala Boundary Commission was set up. F. W. Brunton was this country’s representative on the Commission. Thereafter, the Guatemalans were party to every step taken, every important decision made. The British, through British Honduras, would provide all the labour and field work as well as the map work. The Guatemalans would closely monitor the field operation through frequent on-site inspections and consultations. Since the boundary line between Blue Creek (a branch of the Rio Hondo) in the North and Garbutt Falls (on the Mopan River near Benque Viejo) was already open and accepted, this operation would deal with the section from Garbutt Falls to Gracias a Dios (on the Sarstoon River in the Toledo District), a distance of eighty miles.

To better understand and appreciate the enormity of the task facing the surveyors, it is necessary to know a little about ground surveys. During a field survey, data is collected (mainly directions, distance, elevations, and the like) that can later be put on a map. Running a line from point A to Point B is fairly simple – if you can see B from A. You just set up your theodolite (the state-of-the-art instrument of that period), take the direction in degrees, minutes, and seconds, then measure the distance with a steel tape. The moment you can’t see B from A, the problems start. The farther apart the two points are the more complicated things get. When the two points are eighty miles apart the problems become monumental. Add to this the fact that surveying is one of those tasks in which your errors accumulate. If at point A you stray just one-tenth of an inch from the true direction, the error will increase as you proceed. By the time you get abreast of point B you will be way off the mark. The greater the distance between A and B, the farther away from B you will end up. Just check it out for yourself.

The big problem was to determine the direction from Garbutt Falls to Gracias a Dios (and vice-versa) as accurately as possible. In consultation with the British, it was decided that this information would be obtained through the application of the method of triangulation. This concept is based on the fact that a triangle has three angles and three sides. The three angles must add up to 180 degrees and each accurately determines the directions of the two lines enclosing it. This was a tried and true method. The Frenchman, Jacques Cassini, had used it extensively in the 18th century to survey and prepare a very accurate map of Paris, France. The British themselves were currently using it in their survey work in Africa. It involves dividing the entire land area into triangles. However, in order for it to be properly executed and give very accurate results, a lot of calculations and computation of angles and distances has to be done.

Fortunately, there was a man on the British Honduras Survey Department staff who was extremely good at this type of calculations. He was G. A. Elliott, an Englishman. The man did almost superhuman work, considering that this was long before the age of calculators and sophisticated mechanical calculators. This phase of the operation was designed and supervised by G. S. Busby, another Englishman, a Senior Surveyor with the Department. The actual field work was done by all the surveyors, mainly in their spare time, as normal work had to go on. Triangulation began at Northern Lagoon and proceeded to Benque Viejo (easily and well-defined points.) Guatemalan representatives on the Boundary Commission were there in full force to witness the commencement of the work. The triangulation phase of the work took four years to complete.

By 1933 the triangulation was completed and all the relevant information collected. It was time to begin the actual opening of the boundary line. The decision was taken that two crews would work on the line simultaneously. One team would start at Garbutt Falls and work their way south. The other team would start at Gracias a Dios and work their way north. Imagine the pleasure and satisfaction experienced when two British Honduran surveyors (not the expatriates) were selected to head these teams, although this could also be viewed as the British covering themselves in case things went wrong. Arthur Wolffsohn was in charge of the Gracias a Dios team. He was a native of the soil but had received his training abroad. The other native, placed in charge of the Garbutt Falls team, was Jim Waight. Now this was a remarkable choice, as this man had received all his training in-country. Their assistants were also British Hondurans. Three were newly-qualified surveyors recruited (through the apprenticeship programme) as part of normal expansion of the Department. Allan Anderson was attached to Arthur Wolffsohn while Henry Fairweather was attached to Jim Waight. The third, Wilton Young, was left to do most of the normal survey work.

Life on the border was rough and lonely for the surveyors and their crews. Jim Waight and his team, working towards the South, had to penetrate the virtually virgin Chiquibul Forest. Besides the ruggedness of the terrain, this area was characterized by a scarcity of surface water. The only source of water was aguadas (small ponds) which were depressions into which surface runoff collected during the rainy season. Sometimes the water in the aguadas looked like something one wouldn’t even want to put his foot in. Yet, this was the only potable water and the aguadas dictated the location of camp sites, which were rarely convenient to where the men were working. Travelling some distance to the work site each day added to the hardships the men endured. During all this time their only contact with the outside world was the monthly mule team that brought in supplies and mail.

Another difficult feature of the border line operation was that obstacles could not be avoided or side-stepped. The surveyors had to hold a true and steady course whether they encountered hill, gully, escarpment, tree, large boulder, or anything else. In a regular survey they would sometimes take offsets and go around major obstacles, but here the distances were too great and the danger of error accumulation too real for them to take the chance. These intrepid men had to stay the course through thick and thin without wavering.

Living and working in such isolation, there was one dread constantly on the men’s minds. The chances of survival if injured were very slim. A broken leg, though bothersome, was minor compared to some of the other things that could happen. A man crushed by a falling tree, if not killed outright, could suffer extensively before he could be gotten to competent medical care. The number one fear, of course, was snake bite. Snakes were encountered on an almost daily basis. Eternal vigilance and faith in bush medicine were essential. Fortunately, unlike in some other countries (Brazil, for example) the men did not have to worry about being attacked by hostile people. Still, all in all, while working on the border line these men literally had their lives on the line.

The men stuck doggedly to their tasks day after day, week after week, month after month – for almost two years. One morning the Waight crew got on the work site rather late. They had changed camp site before proceeding to where they had left off on the line. On arrival there, Waight could have sworn that he faintly heard the sound of chopping in the bush not too far away. He knew that he was literally in the middle of nowhere. Nobody else was likely to be mucking about in the immediate vicinity. He was somewhat puzzled for a while. It even flashed through his mind that perhaps the assumption about the non-existence of hostile people was not correct! Somewhat worried, he sent a couple of armed men to investigate.

It took some time for the men to return with a report. In the meantime Waight set up his instrument and continued working. When the scouts did return, they were very excited. They had encountered the team coming from the South! Waight and his team had been living in isolation for so long that he had clean forgotten about the other team coming up from the South.

The scouts brought back a message from Arthur Wolffsohn. He was impressed that they were within hearing distance of each other. Had their accumulated errors been excessive they could have passed each other without even knowing it. He also added that the two teams should come abreast of each other some time that same day. Everyone was elated that it appeared that the teams were well within the parameters set for the operation.

At about three o’clock that afternoon the two surveyors came abreast of each other. They were a mere sixteen feet apart as if across from each other in a spacious sitting room. Unlike the historic meeting between Stanley and Livingstone, though, they did not keep their cool. Wolffsohn, a man of small physical stature and normally very serious, rushed over to Waight, picked him up by the legs and began whirling and dancing, all the while shouting at the top of his lungs! The younger surveyor was more subdued, but still bubbling with pride and joy. And they had reason to be joyful. Between the two of them, in a combined distance of eighty miles, their accumulated errors were only sixteen feet – indeed a remarkable feat by any standards. The colonial boys (one of them fully home-trained) had not only measured up to, but exceeded, most international standards.

Fortunately the mule team was still in Waight’s camp. It had made an unscheduled supply run so as to be there to assist in the moving of camp. Early the next day it was despatched with a brief report to the outside. Within some ten days the Guatemalans were there to see for themselves where the two lines met. During that period, the surveyors were busy making all the adjustments so that the two lines fully coincided. It was a great photo opportunity for all concerned.

Enough cannot be said of the men involved in the border line operation. They showed what could be accomplished through hard work, determination, and a sense of purpose. As they deserved, they all went on to hold positions of importance both in-country and abroad:

James A. Waight went on to become the Surveyor-General of Belize, in which capacity he retired. During his career he also acted as Governor of British Honduras.

Henry C. Fairweather reached the rank of Senior Surveyor with the Survey Department. He then continued his studies and qualified as a town planner. He was the first Director of the Department of Housing and Planning, in which capacity he retired.

Arthur N. A. Wolffsohn attained the rank of Surveyor-General, the first British Honduran to do so. During his career he acted as Governor and Colonial Secretary of British Honduras. He was also knighted.

Allan Anderson rose to the post of Principal Surveyor, in which capacity he retired.

Wilton Young became a Senior Surveyor with the British Honduras Survey Department. He then joined the British Colonial Service and was posted to Mid-West Nigeria, Africa, as Surveyor-General.

G. A. Elliott retired as Surveyor-General of British Honduras. He never returned to live in the United Kingdom. He died in Belize.

G. S. Busby came to British Honduras as a Senior Surveyor. Shortly after the completion of the boundary line, he was transferred to Trinidad and Tobago as Surveyor-General.

F. W. Brunton was the Surveyor-General of British Honduras when it all happened. He was forefront in the insistence that the Survey Department could get the job done. During his service in this country, he also acted as Governor of the colony. After British Honduras, he retired from the Colonial Service and returned to England.

Hats off to these men for the valuable contribution they made to our country. We owe them a huge debt of gratitude. Today, even with the existence of the boundary line, the Belize-Guatemala Differendum continues. Imagine how much more difficult the situation would be if there were no border line.

Editor’s note: Mr. Louis Lindo, deceased, was a former Chief Forest Officer of Belize. He is the author of the book, Tales of the Belizean Woods.