In America, they have a saying that goes like this: In the South (slave states), the white man says to the black man, “You can get as close as you want, but don’t get too big.” In the North (abolitionist states), the white man says to the black man, “You can get as big as you want, but don’t get too close.”

In Belize, the elitist group basically says to the roots class, “Just stay where you are. If you try to move up, we’ll put you down.” That’s how I see it after all these years.

As a child in the late 1950s, I saw a sensational group of roots youth emerge as a football team named Dunlop. Then the first spectacular group of roots youth to emerge in music was the Lord Rhaburn Combo, which cut its breakout album in 1962. I guess it was around 1966 that the legendary Messengers musical group came together. Pulu Lightburn’s basketball Homebuilders rocked Belize around 1977, 78.

What happened to these roots phenomena? Well, the major stars of Dunlop were given jobs by the largest business corporation at the time in Belize — the transnational BEC. After two great years of the Messengers, the owner of the musical instruments just took the instruments away from the Messengers, and the group fell apart. The sponsor of the Homebuilders, Rudolph “Sir Andie” Anderson, was cruelly victimized in more ways than one, and the Homebuilders became Jah Jam and Acros Jah Jam. Lord Rhaburn survived and thrived because he was a great diplomat and politician [non-electoral], and he did not smoke reefer. Rhaburn was also a very good businessman.

I did not include the Independence football team amongst the roots phenomena of the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, because theirs is a complex story, and I think it demands serious research. My sense is that the Independence leadership smoked reefer.

I mention this reefer thing, because whereas the Rhaburn group did not smoke reefer, the Messengers were known for their reefer use. Before 1961, middle class youth in the capital city were basically afraid of using reefer. By the time of the Messengers, some of that fear had dissipated.

My column today is not about reefer in the city. That would require, again, serious historical research. I think that smoking of reefer would have been used by the elites to condemn any roots move back then. That’s that.

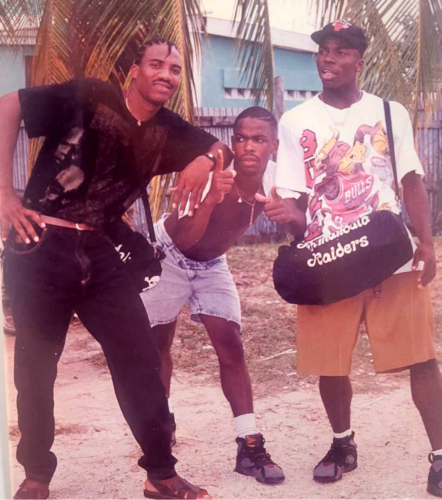

Photo: (L to R): Ray Gongora, Jason Barrera, and Maurice Williams in 1992. (JENKINS)

A year or two ago, Maurice “Reesh” Williams visited me at my home. Williams was a poor youth from Lake I who became iconic in the first semi-pro basketball season of 1992. Maurice was so poor growing up that when he was getting out on the break in the old SJC gym back in the early 1980’s, his “sneakers” were a pair of old policeman’s boots which his dad, a cop, had given him. Maurice Williams was as poor as poor could be.

His time in the Belizean limelight did not last that long, because he hurt one of his knees, and we didn’t have any real sports medicine in Belize. By the way, when the Raiders visited Guatemala City in 1994, Maurice won a slam dunk contest over there. He was only 6′ 1″ tall, but he could really sky, and he loved crowds and big games.

The Raiders were a team with seven rookies who participated in the very first semi-pro basketball season in 1992. Maurice Williams’ fame derived from a move he made in the second game the Raiders ever played. He got out on the break and met the Jam center one-on-one around the free throw line of the southern basket. Williams jumped over him and slam dunked. The old Civic, which had never seen anything like this, went wild. (The late J. J. Lynch of the Homebuilders had done it at Bird’s Isle in the late 1970s.)

Reesh had come to work as a collator at this newspaper when he was about 10 or 11 in the early 1980s. He became close friends with three fellow workers — Willie Gordon, Earl Nunez, and Jason Barrera. On Friday afternoons after work, these four would catch a bus west or north and get into pickup basketball games of “21” on the road. Williams, Gordon, and Nunez were the players; Barrera was the manager.

Maurice Williams migrated to the United States about twenty years ago, to the city of Boston, I think. Willie Gordon was shot and killed a couple years ago in the city streets. Earl Nunez died in Chetumal some months ago. He had migrated to the States a couple decades before that, but something went wrong for him over there and when he returned home, he was only a shell of his former self. Jason Barrera became Belize City mayor Bernard Wagner’s driver and friend in 2018 after three-plus decades at this newspaper.

When Maurice visited me, there was a joy in him, but there was also a sadness. The sadness had to do with the fact that when he had visited the new Civic, there was nowhere he could find any banner or memento of the Raiders, who won four straight championships (from 1993 to 1996), and then three more after semi-pro was re-organized in 1999.

I feel that Maurice Williams earned the right to be remembered in basketball annals here. He was a nobody who became a somebody, and then the people in power returned him to nobody status. Like that. There was a time when Maurice Williams practically owned the Civic. What would it cost for him to be given his respect?

Part of the problem is that when Kremandala sponsored sports teams, the rest of the media here treated these teams as threats, as if the teams were part of the media competition. Our young athletes paid the price for this misconception.

It’s not too late for the people who run the Civic to put something in the place which honors the accomplishments of the Raiders. In so doing, they would please the soul of our boy Reesh — the nobody who became a blazing somebody.