The Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, has said:

“The best of what a man leaves behind are three: a righteous child who remembers him in prayers and makes supplication for him, ongoing charity that benefits the poor, and beneficial knowledge he has taught that is acted upon after him.”

When Brother Sarafa and I left Belize City last Sunday morning on our way to Cayo to prepare our brother, Saeed, for burial that afternoon, I had many thoughts running through my mind as we drove along the George Price Highway on a quiet and somber, but beautiful, day. I thought about my own death and how fleeting this whole life is and how much we take time for granted. I thought of the advice of the Prophet, that during funerals that we try to think only of the positive character traits of the deceased and avoid any reference to any negative experience, which is now in the Hands of Allah. As I reflected on that piece of advice, I smiled, because I had nothing but good thoughts about my forty-year friendship with Saeed Abdul Karim. The small hiccups here and there along the way pale next to the overwhelming experiences of good vibes together.

As we turned off the highway into Clarissa Falls toward the village of Calla Creek, I couldn’t help but give Sarafa, who is originally from Burkina Faso, West Africa, a short history of Clarissa Carter and Thomas Paslow. And as we drove along, the beauty of the water and families bathing on the banks of the river made the journey even more rewarding.

Saeed’s property is in Calla Creek, a village which seemed to be surrounded by hills. His house is on one of those high hills overlooking a splendid view of the surrounding valley. I am told that he personally participated every step of the way in the construction of his house with his specific design of a Spanish architectural circular model, influenced by Islam in Spain in the 7th century. The windows and doors were all arched, and at the center of the circular structure is a garden. The location on the summit of the hill and the structure and its design spoke of the free spirit and vision of Saeed.

Before a Muslim is buried he/she is purified by a complete cleansing, perfuming and shrouding of the body with white linen cloth. Men prepare men, and women prepare women. Four brothers participated in the preparation of the body of Saeed.

Saeed’s instruction was that he be buried on his property, so a place was prepared at the bottom of the hill, by the roadside near an open field, nuzzled under a patch of tall bamboo trees towering over the grave, almost as if on guard.

The burial prayer (Janaza) was led by the Imam of the Muslim community in Belize, Kaleem El Amin. The ceremony was attended by his family and friends. The attendees reflected the wide scope of the friendships he had formed over his forty years in Belize. There were persons from every walk of life, including several non-Belizeans. Saeed was a magnet for people—that wide smile, that inquisitiveness, that sense of humility and that ability to laugh at himself, like when he was learning to talk Creole, which he never mastered, are some of the things that endeared him to all of us.

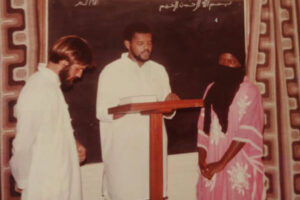

I first met Saeed in 1980, in Guyana, at a two-week intensive Islamic training course that was conducted by Sheik Daud Abdul Haqq of Barbados, and was sponsored by the late Libyan Ambassador to Guyana, Ahmad Ehwas. The course was attended by representatives from throughout the Caribbean and Latin America. Belize was represented by Muhammad Raees (Anthony Reyes) and Grandville Omar Hasan (Granville Hermond). Saeed represented his home country, Argentina.

As Imam of the Muslim community at the time, I attended the closing ceremonies. When I was introduced to Saeed I immediately noticed the special bond that had developed between himself, Raees and Omar during the course. They were inseparable. Saeed spoke of how much he would like to come to Belize and that he had lived in several countries but had never heard of Belize until he met Omar and Raees. Years later he always credited Raees’ persuasiveness in Guyana for his decision to come to Belize. It was soon after an extended one-year course later in 1981, which again Raees and Saeed attended, that Saeed arrived in Belize.

Saeed was an incredible character. After coming to see for himself, Saeed immediately fell in love with Belize and decided to end his search for that place he had been searching for. To understand what I mean by incredible, let me share with you the surrounding circumstances that were going on in Belize and particularly in the Muslim community when Saeed arrived in 1981.

Belize was in the throes of the pre-independence issues – early in ‘81 was the riot surrounding the Heads of Agreement and the speedy rush to independence in September, under a state of emergency. One of the dominant personalities on the national stage at that time was another Muslim, the late Odinga Lumumba, who along with Saeed and another brother, Ali Beyah (Dilbert Latchman), were staying at the Masjid on Racecourse Street. You can imagine the level of conversations that were taking place among the brothers during this period. Lumumba was a leading figure during the Heads, but Saeed also had a history of roots in the struggle; he understood very personally the power of oppression. His brother was murdered by the Argentinian junta that had “disappeared” thousands of Argentinians during that period that was called the ‘dirty wars’. So as the events were unfolding in 1981 Saeed was fully engaged. I used to tell him he reminded me of Che Guevara, another free-spirited Argentinian.

One of the traits of Saeed’s character that I think may have attracted many black Belizeans to him was his unassuming personality and a demeanor that displayed that he didn’t think he had any special privilege because he was white. In the context of the Belizean perspective, Saeed was a “white man”, but his mind and behavior were not like that American TV white man that we were used to. The usual vibes of white entitlement that you find in many Caucasian men was absent from Saeed. He was poor and humble, and he was always in a learning mode. He was different, and he accepted his difference and many times laughed at it. I remember him laughing when telling me how his football team mates nicknamed him “white boy” when playing at Yabra, but how he was well-respected for the skills he brought to the game.

I think he had fallen in love with what he saw in Belize, its people, its culture, its freedom and its vast potential and how easy it was to get land in Belize compared to any other place. He completely absorbed himself into grassroots culture. It was interesting to me to observe that in Saeed’s early sojourn into Belize he didn’t choose to mix with the highti-titi of the society. He could have very easily used his “white privilege” to mix-and-marry and find a way to establish himself in Belize, as so many others have done and continue to do. But from those early days, forty years ago, brother Saeed chose to rise among the grassroots.

I believe this can directly be attributed to the fact that Saeed was a member of the Muslim Community which, at the time, was a community of predominately poor black people. We began to evolve out of the “blacks only” membership restrictions of the Nation of Islam into the universal brotherhood of Islam in 1975. While we had made the change after the passing of the Hon. Elijah Muhammad in 1975, six years later, we were still in what you could call a transition, so the presence of Saeed, the first “white Muslim” in the Belize Muslim community at that time, was a phenomenon in itself.

Coming to Belize as a trained Muslim missionary, he immediately involved himself with the development of the community, including training sessions for new Muslims, working land programs and outreach service to the wider community. In time, through his sincerity and work he became a part of the Management Committee (Shura) of the Islamic Mission Belize. In fact, Saeed represented the Belize Muslims community at a conference in Saudi Arabia.

He married a Muslim sister, Janice Young, from Gales Point. I was honored to perform that marriage ceremony. Janice and the people of Gales Point taught Saeed the art of bamboo craft, and together he and Janice became the pioneers in the exposition of this eco-friendly, indigenous, sustainable, craft development.

Saeed had three children with his first wife —Ashanti, Kadijah and Amal, and two children with his second wife, Tarik and Aliyah.

For the purpose of this article I had a conversation with Muhammad Raees, and he shared with me one of the last conversations he had with Saeed while he was in Argentina for medical treatment. He said he didn’t consider himself a citizen of Argentina anymore; he had made Belize his home for forty years, so he was a citizen of Belize, but the best definition he had of himself is: “citizen of the world.”

Elsewhere in the media are stories covering the entrepreneurial skills of Saeed Abdul Karim Assales. Mine is only a personal reflection of my brother and friend, and our days together in the early eighties. He was one of the freest spirits I have ever met.

May Allah forgive him his sins, make easy his rest in the grave, and raise him into the paradise.