I recall writing about the cows at Central Farm in a piece I produced around the time of one of our annual Agricultural and Trade Shows (because of COVID-19 there was no show this year), and this week I remembered the cows after thinking about things that Belize must produce if she will survive as an independent, free country that provides for all her people.

I was relaxing on the verandah of my parents’ Belize City home when my uncle, the late James V. Hyde, sent someone to tell me he wanted to see me downstairs of my aunt’s home. My aunt, the late Chrystel L. Straughan, lived just next door to my parents’ house, so I went over immediately to see what he wanted to talk me to me about. My uncle told me that the government was starting a new agricultural school in Central Farm in September 1977.

At the time I was a fisherman, doing pretty well too, but all my family knew that I also liked agriculture. When I graduated from high school I astoundingly had sufficient passes in the O’ level exams to satisfy Belize’s requirements for a scholarship to junior college, and when I turned that down one of my father’s two strategies to encourage me to further my education was to suggest that I put in an application to study agriculture at Zamorana. Incidentally, there mustn’t have been that many scholarly youth in Belize in the 1970s. I sat five O’ levels and scraped them all. That was sufficient.

My uncle told me that the government had decided that Belize would produce its own milk, and after graduating from the school the students would get land in the Belize River Valley, and a few cows to get them started. He told me that I didn’t have much time to think about it because the school had already held exams in all the districts, except for Stann Creek, but if I stepped to it and filled out the application he could get it in for me.

My uncle arranged for me to overnight in Dangriga, at the home of our cousins, the Locke family. I was in Dangriga a couple days later for the exam, and I was successful.

It wasn’t a difficult decision to go country. When the call came for me to go back to school I had been on the sea for two years, the first with my brother, Charles, and the second with my high school buddy, Taachi Avila. To keep this sea part of this story short, Charles was and is far and away a better fisherman than I was, and so was Taachi.

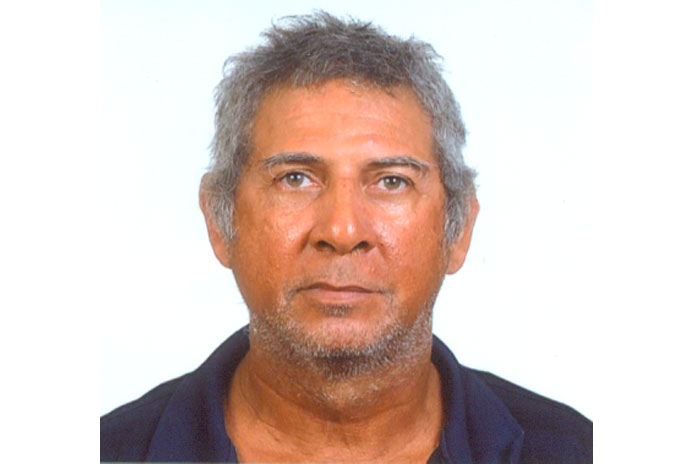

I am a terrible fisherman. Part of my problem is that some of my white genes are in my eyes, and so I can’t see well when I’m out in the sun. I could have used sunshades when I was on the sea, but in my youth I thought that was only for “soft-pops” movie stars. While I learned to enjoy movies, I don’t rate actors. We are who we are, and I am a person who not only can’t say the same thing the same way twice — I won’t. Whoa, unscripted is dangerous, so I keep a very low profile.

I noh humble about my seamanship, but I ain’t worth a daam on the fishing. I didn’t ask Taachi’s advice about heading off to agricultural school; I told him I was going away for a year, and when I returned we would do the lobster trade, which we engaged in two days each week, and then we would get land around our old stomping grounds, Belmopan, and do the farming thing. The short of that is that after he took some time to think it over, he did not agree with the arrangement, and so I sold him my shares in our fishing business.

There wasn’t much talk with us boys – 21 of us, I think, at the new Belize School of Agriculture – about a milk project, maybe because the government had already decided against it, maybe, but handling the dairy herd at Central Farm was part of our training. We took turns in the dairy routine —3 boys in the morning rotation each week. For me it was the best part of going to school at Central Farm.

You have to milk cows every morning and evening, or they will get sick, and our job was to bring them into the milking parlor. When we were on rotation, we had to set out at 5:00 in the morning to cover the mile or so to the pastures to get the cows in by six. Bringing in the milk herd was a rich experience – I can never forget their smell, their hulking bodies lumbering through the fog, their distended udders swinging gently from side to side as they plodded steadily toward the milking parlor for a prize of ground corn and vitamins with molasses, while they enjoyed the sweet release of their many liters of nutritious milk.

Bringing in the cows always reminded me of an early morning at cay, of getting up before the dawn for a fishing trip, but there was always some disquiet in my heart because it was my plan to return to the sea, to work both land and sea, and a milk herd must have the full, undivided attention of its master.

I don’t know how it is with you, but it is so sometimes with my little brain that I cannot see past the simplest things. It is no problem for me to set my sails and not look back until I have reached where I set out to go. I once got involved with a project and, going on two years, Sunday to Sunday, I still hadn’t blinked.

I couldn’t figure out how I could run a dairy farm and still spend some time at sea, and that dulled my desire to be with the cows. I love those animals. I saw a little show the other day with a cow that went to the village hand pump to get water when she was thirsty. Every time the water stopped flowing she wrapped her mouth over the handle of the pump, gave a couple strokes, and then quickly shifted her mouth over to the spout to satisfy her thirst.

Ai, I eat beef…happen to love it. I still drool over a slab of rib-eye that my roommate at the Belize School of Agriculture, Escander Bedran, Jr., gifted me the last time I saw him at the Agric and Trade Show. After I had the first bite I told him he’d have to excuse me, because I had to go find a corner, all by my lonesome, to enjoy my feast.

About my confusion on what professional path to take, it was oh so simple. All I needed was a partner or an employee I could trust, so that I could go off to the salts when the call could not be denied.

The first class of the new Belize School of Agriculture graduated, and there wasn’t any mention of milk. Most likely it is the economists who threw cold water on such a vital project. The conspiracists might have a different story, but my bet is that our textbook economists missed the full story of milk production, and thus this valuable industry was relegated, back-benched, put in the dust bin.

There was a farmers’ cooperative, Macal Dairy, that tried milk production, but it wasn’t smooth sailing. I believe that later on the Big H family of San Ignacio took over the project, but they didn’t continue it for long. Of course, the Mennonites’ Western Dairies has been producing milk and cheese and ice cream for years.

I don’t have to do any research to tell you that business with the Mennonites is far different from business with us. The support system in the Mennonite community far surpasses anything the roots farmers of Belize get from the government, and the economists add weight on our farmers’ shoulders with policies that put us at a big disadvantage.

We could have had a milk industry a long time ago, and we are better positioned to have one now. Point blank, if the government gives our farmers fair incentives, we will have a milk industry. If the big milk importers, Castillo and Brodies, decide to invest in local milk production, we will have a milk industry. You don’t have to take my word that it is more than viable. I’m going to present the story of dairy, and the numbers, soon.