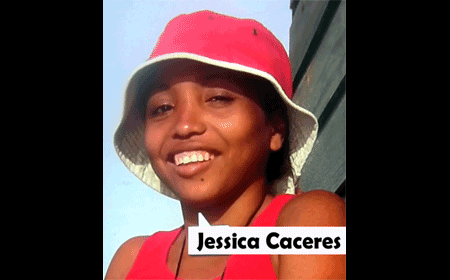

BELIZE CITY, Tues. Apr. 12, 2016–The Caceres family of Belize City are still hurting over the untimely death of 21-year-old Jessica Caceres—the last of three patients to survive after the fatal transfusion of HIV and Syphilis-tainted blood back in March/April 2001.

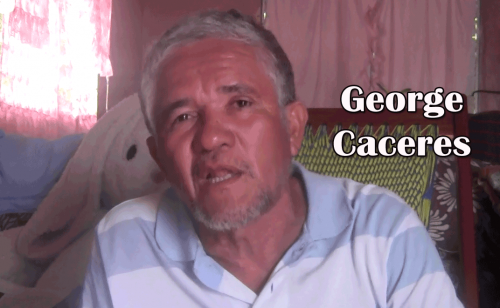

“She was my only daughter and it hurt me big time,” George Caceres, Jessica’s father, told Amandala. He said that what the family has experienced is “a complete injustice.”

Although the family settled for BZ$75,000 in October 2002, when Jessica turned 18 she sought the help of the Ombudsman’s Office for a more just compensation. Since 2013, the Ombudsman has knocked at every possible door—the hospital where Jessica was infected, the Commissioner of Police, the General Legal Council, the Medical Council and the Office of the Prime Minister—but there was no notable progress in her case.

The father questioned whether justice had been served not just by health authorities, but also by the attorney he had gotten to file a lawsuit, which, he said, was not filed within the one-year statute of limitation.

The tragedy was the subject of a Commission of Inquiry led by former Chief Justice, the late Sir George Brown, who was joined by the late Dr. Leroy Taegar and former Ombudsman Paul Rodriguez. Rodriguez told us this week that he remembers the case clearly—although it happened 15 years ago. The Commission, he said, was not tasked to look at the question of compensation for the patients but at trying to uncover what led to the transfusion of the tainted blood.

Of note, though, is that the incident sparked legislation to criminalize the deliberate transmission of HIV to another person.

The recently tabled report of the Office of the Ombudsman, Lionel Arzu, highlights the case of a young woman, not named in the report, who recently died after more than a decade of struggle against HIV/AIDS.

According to her family, Jessica suffered from pain, seizures and ulcers, and she was put on a cocktail of meds to fight off the virus. Her father said it was like she had a pharmacy at home. He said that he and his wife took turns caring for Jessica at nights, and his wife had to leave her job to care for their daughter. She wants to know what happened to his wife’s compensation for having to leave her job under the circumstances.

The Ombudsman’s report indicated the patient was infected in 2002, but her father informed us that she had actually been infected in 2001, along with two others who had been hospitalized at the Karl Heusner Memorial Hospital (KHMH).

At the time, Caceres’ name was not released. She was only 6 then, and had since been having to live down the stigma and discrimination commonly suffered by people living with HIV/AIDS. We are releasing her name now only with the explicit permission of her father, who wants her story to be told—in the hope that something could be done to bring just closure to her case.

“I want them to know that I am not happy,” Caceres told us.

In the April 15, 2001 headline story carried by Amandala, captioned, “Death was in the blood,” we had reported on the tragic mishap which resulted in three KHMH patients—Luecilli Rena, 31; Andy Myers, 2 months; and Caceres—receiving blood tainted with HIV and Syphilis. The blood had not been screened before it was given to the patients, and at the time, we had reported that the hospital was taking full responsibility for the patients, who were immediately administered anti-retroviral treatment.

Sadly, Rena, who had been admitted for gallstone surgery, which evidently did not go as planned, died on April 28, and Myers, who was being treated for a rare skin condition, died shortly after the transfusion. Both Rena and Myers had reportedly died of causes unrelated to the HIV infection. Only Caceres, who had been diagnosed with sickle cell anemia, survived. Her health problems worsened when she became a teenager.

Her father took us back to the days when the tragedy began to unfold. He told us that they were going to see the carnival when Jessica fell and broke her collar bone. They immediately took her to the hospital, where Dr. Egbert Grinage attended to her. While running tests on Jessica, they found out that she had sickle cell anemia. The family was told that sickle cell anemia is rare in Hispanics, but her father explained that his father is a Black man and his mother a Hispanic.

Months later, the family was told that Jessica’s blood level was low. She had suffered a stroke, which paralyzed half her body. It was around this time that the doctor ordered blood for Jessica. Caceres said that she was to receive blood every month and all was well until March 2001.

Caceres said that he questioned the doctor when he saw that the bag of blood that was being given to his daughter had “a cute color,” but the doctor indicated that it was not possible to tell if something is wrong with the blood by just looking. The father said that he had been told that this was the same type of blood that had been ordered for Jessica before.

It had been reported in the media that the blood, which was later found to be tainted, was given as a replacement batch for blood from the Blood Bank that had been used in surgery for the donor’s relative. The Commission of Inquiry had revealed that the blood had, in fact, not been tested before being used for the three patients.

Soon afterwards, Caceres said, KHMH representatives went to see him and said that they wanted to speak with him. They put an elderly lady to speak with him.

“How would you feel if they tell you your daughter is infected with HIV?” Caceres said he was asked.

“I said, ‘Repeat that?’ …I felt like the world fell on top of me,” Caceres shared.

He said that when Jessica turned 6, he bought her some parrots, which are still being kept by the family today.

“When my daughter passed away, the birds took two weeks before they said anything,” her father said.

The birds filled the void left in Jessica’s life because neighborhood children were afraid to play with her. Her father said that he had built a swing and slide in the yard so that other children would come and play, but they did not.

According to Caceres, he had given the late B.Q. Pitts “all the evidence to show he has a winning case for Jessica,” but the case was never filed. He told us that over a year later, a vehicle came to his house from the Minister of Health and they said that they wanted to see him in Belmopan and if he went there with any lawyer they would not attend to him. He was told to go with his wife, Irma.

A government vehicle took them to Belmopan, where they met with former Solicitor General Elson Kaseke, now deceased, and Minnet Hafiz, who is now a Justice of the Court of Appeal.

“They let me know, ‘I have $75,000 for you.’ I said, ‘That is too little,’” Caceres said.

He said that he was advised that if he did not accept, he would not get anything.

They received a check to build a home for Jessica. They built a two-storey concrete home, where the family still lives.

“I told them, ‘What happened to the future of the little girl?’” the father recounted.

They said they would give another $75,000 for future expenses, Caceres said, adding, though, that this was not put in the written agreement he and his wife had signed.

That agreement committed the Government to providing free medical care and education for Jessica for the course of her life. Jessica attended Holy Redeemer Primary School and Anglican Cathedral College.

“We’ve had approximately 10 to 13 letters from the Ombudsman, sending to the PM, to the Ministry of Health, the Hospital… not even the PM, no one answered the letters,” Caceres said.

“It hurt me when the Ombudsman told me that they can’t do anything else,” Caceres lamented.

He said that what was done to him and his family was an injustice, including being denied the right to adequate legal representation.

Caceres said that he also found out, after the fact, that Pitts was the father-in-law of the doctor who had attended to Jessica and on that basis, he filed complaints to both the councils for lawyers and doctors, but nothing came out of those complaints.

For the first few years after Jessica got infected with HIV, people were generally supportive including the Government, but that support faded away, Caceres told us. When Jessica passed away last year, the only official help they received came from Collet area representative, Hon. Patrick Faber, in whose division they live. Former Port Loyola Area Rep, Dolores Balderamos-Garcia, with whom we chatted about the case this week, said she also helped out the family in her official capacity.

Amandala had published a Cabinet news release dated July 10, 2001, which reported that then Prime Minister, Hon. Said Musa, had received the report of the Commission of Inquiry with recommendations to avoid a recurrence. The Attorney General’s Office was tasked to review the report and determine Government’s liability.

Meanwhile, Balderamos-Garcia, who at the time was the minister responsible for Human Development, had proposed new legislation to criminalize the intentional transmission of HIV, as well as reckless behavior in which a person’s own actions deliberately leads to the contraction of the virus—since such an action would bring unnecessary costs to the Government, which has been providing care for HIV patients.

However, Caceres laments that when Jessica died last December, there were no condolences from the ministry.

The father also questions the circumstances under which Jessica died at the KHMH. He said that no post-mortem was done, and the attending physician indicated that none was needed, since they knew the cause of her death. The death certificate said that she died from pneumonia.

Caceres said that two of his children had been admitted to the hospital for respiratory illnesses, but the other, his son, recovered. Jessica didn’t. He received a call moments after leaving her at the hospital in good spirits that she had died. When he returned to the hospital, Jessica was being administered CPR. According to the father, medics tried about 7 different machines to resuscitate her but none worked. He said that a muscle relaxant was given to his daughter which he believes, accelerated her death, but an internal investigation by the hospital found that there had been no wrongdoing.

Although the Ombudsman has told us that the death of Jessica in December would likely result in the closure of the case, her father appeals for help from a trained attorney who is interested in looking at other angles to the case to determine what next steps they could take in trying to bring justice for Jessica.

Caceres pointed to the $2 million awarded handed down by the Caribbean Court of Justice in 2014 in the case of Janae Matute and her mother, Georgia Matute, both of whom were awarded compensation in a medical malpractice suit that exhausted all possible appeals. Janae, who is now a high school student, had developed cerebral palsy due to a series of unfortunate events which unfolded at her birth.

No individual has been held accountable for the tainted blood transfusion of 2001. Ombudsman Arzu tried to probe police on whether action could be brought under the criminal code, revised after the April 2001 incident, but as far as we are aware, no such case has been brought to the courts.