I have always been hesitant to discuss young people in this column, because my personal generation, which grew up in the 1960s, was one of planet earth’s most controversial young generations ever. In British Honduras, Hurricane Hattie in October of 1961 changed my post-World War II generation in that Hattie opened up the United States for us to an extent we had only been dreaming about previously. The effects of Hattie’s destruction changed our domestic socializing mores: socializing became more liberal and less old-fashioned. (I think it was during the years after Hattie that the birth control pill came on the scene in Belize.) We began to view ganja with more favor.

In the United States itself, the so-called Cuban Missile Crisis in October of 1962, followed by the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in November of 1963, the rapid escalation of the Vietnam War in 1965, and the increasing militancy of the black civil rights movement affected members of the American student population who were around my age in dramatic ways.

Traveling to the United States, as an innocent, to study in August of 1965, I eventually became caught up in the socio-political ferment of America, and by the winter of 1967 I had become relatively radicalized. During my years in the United States between 1965 and 1968, America arguably became more violent politically than it had ever been. Students began protesting violently against the Vietnam War, and the national cauldron of violence bubbled over with the high profile assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, a Nobel Peace prize winner, in April of 1968 in Tennessee, and that of Senator Bobby Kennedy just weeks later in California. Bobby Kennedy was the younger brother of President Kennedy, and he was a candidate campaigning for the Democratic Party’s 1968 presidential nomination when he was killed.

One of the reasons the 1960s were so turbulent was because this was the time, in the aftermath of the aforementioned Cuban Missile crisis, when young people in the rich, developed societies of the world became conscious that the planet itself and all we human beings were in danger of being destroyed by nuclear war.

I had a white friend at Dartmouth College who influenced me in a revolutionary direction and I don’t know that I have ever discussed with you readers. I guess this was because my friend was so cool and understated. His name was George E. Moore, and he was from a small town in Pennsylvania with an unforgettable name – Punxsutawney. He lived in the same dormitory as I did – Bissell Hall, and belonged to the same fraternity as I did for a while – Zeta Psi. George was a Roman Catholic, but he became radicalized by the Vietnam War.

We graduated from Dartmouth the same year of 1968 and I went our separate ways. (I’m sure that at the time I would have been more concerned about my friend from Malawi, Guy Mhone, who could not go home after graduation.) In late 2013, leafing through some of the material the university is always sending its alumni, I saw some biographical material on George, including his e-mail address, and decided to mail him on a whim. He remembered me, and we corresponded for a while. George had drifted in the radical student world for a few years, but then he went to law school. He ended up becoming a senior vice-president of Temple University, one of the most prominent in Philadelphia. He told me that one of his daughters had actually visited Belize for a vacation one time, and perhaps he would check me out some time. George mentioned that he’d beaten prostate cancer and pancreatic cancer, but that he was dealing with a recurrence of the pancreatic. I did not pay this as much attention as I should have. George mentioned it in an offhand way, that was George, but I should have paid more attention. Seriously.

I guess I just began to wait and see if he would visit Belize. Weeks turned into months, then a couple years. A few weeks ago, I said to myself, let me see what George Moore was up to. My e-mail to his address was not processed. George Moore had died. I started saying to myself, I waited just a little too long to reconnect. But George Moore had died from early in 2014. When he was talking with me through e-mail in late 2013, George was a dying man. He never gave me those vibes. I salute his courage, and I mourn him. George was special.

Most American students of George Moore’s generation who rebelled against the Vietnam War and domestic injustices in America in the 1960s and early 1970s, later returned to mainstream America and became rock solid citizens. The point is that you can’t give up on young people: we older ones must always have patience with them.

Personally, I spent years in Belize’s socio-political wilderness, and I committed my share of sins. It is for this reason that I have been hesitant to comment on young Belizeans through the years. I believe now, though, that at this critical and dangerous point in the history of Belize, we have to wonder if our young people have not been misled around here. Are our young people focused more on looks and sexuality than they are on intellect and character?

It is absolutely normal for healthy young people to have major interest in looks and sexuality. But, going for three weeks after Jimmy Morales’ open military threats against Belize, fifteen months after a Guatemalan campaign against Belize’s sovereignty and territorial integrity became evident at the Sarstoon River, and years after the Guatemalans began to pillage the Chiquibul, young Belizeans have yet to step forward and make themselves heard.

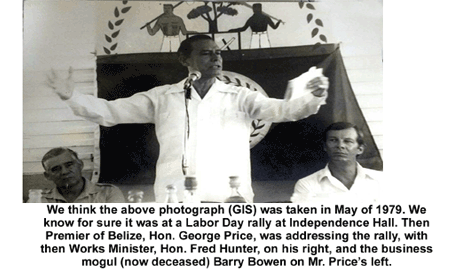

It is true that Belize’s young people have been under systematic attacks on their minds and their souls. While Guatemala has been preparing her young people to take Belize, Belize has been emphasizing carnival for our youth. The priorities in The Jewel are misplaced. If you couldn’t see it before, you have to see it now. It is not the young Belizeans who are to blame. The people who are in charge of running this ship have encouraged a party mentality. This is one of the side effects of tourism. If we want to own The Jewel for ourselves, then we Belizeans have to put in real work. In the famous and crucial words of the Rt. Hon. George Cadle Price: wake up and work!

Power to the people!