by Khaila Gentle

July 21, 2022

The publisher of AMANDALA, Evan X Hyde, once wrote, “you can go to school in Belize from you are 5 until you are 55, and you will never know anything about the 1919 riots and what led up to them.”

A hundred and three years ago, on July 22nd and 23rd, over 3,000 black men, women, and children took over what was then known as Belize Town in protest of the blatant racism, inequality, and systematic oppression that they had been subjected to for years at the hands of the British administration and upper class “elite” Kriols.

They took to the streets, marching down Albert and Regent, across Swing Bridge, and down Queen Street and North Front Street.

It was a pivotal moment in Belizean history—one that would become known as the 1919 Black Revolution to some and the Ex-servicemen riots of 1919 to others. Still, not many Belizeans today are aware of the two-day uprising or the days—and years—leading up to it. In fact, many know more about the Battle of St George’s Caye, which took place an entire 121 years prior, despite the fact that British Honduras was merely a small settlement when that battle took place.

Those who do retell the story of the 1919 Black Revolution often do so through a very narrow, very male-centric, and very sanitized lens—something which the UBAD Educational Foundation (UEF) is hoping to change.

In a spirited conversation about the revolution and the years of frustration that led up to it, UEF Chairperson YaYa Marin Coleman spoke with me about the way the prevailing narrative of the Revolution paints a poor picture of what truly happened.

According to historians, on Tuesday, July 22, 1919, over three hundred black veterans, disgusted by the racism that they experienced at the hands of white troops while they were away at war and frustrated by delayed pay, and a lack of access to land and jobs, took to the streets. They were eventually joined by thousands of residents of Belize Town, including police officers.

Those soldiers, descended from African slaves, had left the comfort of their homes to fight for Queen and country and were met not only by the perilous trenches of the Middle East but by inhumane treatment from colonial authorities. They were made to live in unsanitary, unlit, quarters, clean latrines, serve the Europeans, and bury the dead, and they were often abused both physically and verbally by their European counterparts. Additionally, they were barred from mess halls, playing fields, bathing quarters that were deemed “whites-only”.

But the situation back home, which historians often fail to acknowledge, was no better. Residents of British Honduras, throughout the 1800s and 1900s, had to contend with rises in the cost of living, a lack of job opportunities, decreased wages, and, yes, racism—a chapter from Anne S. Macpherson’s “Imagining the Colonial Nation” describes, for example, the way a September 10th celebration included blackface minstrels.

The 1919 revolution was not just a brief moment of uprising on the lengthy pages of Belize’s history books. It was, said Marin Coleman, the result of “81 years of buildup,” as emancipation in 1838 did not spell the end of racism and inequality.

“Leading up to the 1919 revolution, people met and organized,” she said. One such organization was the 1894 Labourers’ Riot, when Belize Town residents revolted against a proposed devaluation.

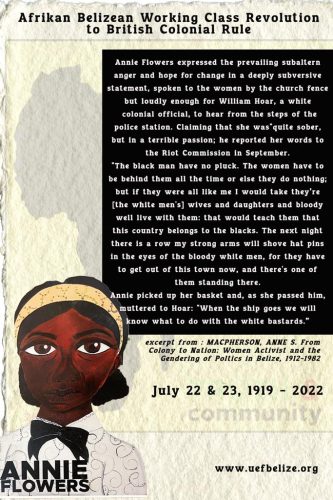

In retelling the story of 1919, historians also fail to acknowledge the role that women played in that crucial moment and many others throughout history. While many are aware of the role that Samuel Haynes played in the revolution, for example, few are familiar with the name Annie Flowers.

To quote Anne Macpherson in her book “From Colony to Nation”:

“Samuel Haynes and Annie Flowers imagined two different nations in 1919 and two different ways of achieving them. Hers was the angry black protonationalism of the rioters, hazily defined but clearly popular, while his was the hedged patriotism of the Creole middle class.”

During the two-day uprising, British officials, fearing that British Honduras could become like Haiti—home of the largest and most successful slave revolt against colonial rule in the Western Hemisphere—requested military assistance from Jamaica. The colonial authorities were eventually able to subdue the revolution, but only after leaders Samuel Haynes and H.E. McDonald reportedly calmed the protestors from within. Some 32 revolutionaries were arrested and jailed, though many of the instigators, including Haynes and McDonald, were pardoned.

Samuel Haynes, who would go on to write the lyrics for the Belize National Anthem, proudly proclaimed himself the reason behind the end of the revolution and the return of power to the colonial authority, stating “If the truth were told, it was I whose appeal to sobriety and reason saved the handful of Europeans in Belize from a savage massacre when the returned soldiers rioted in an orgy of rum in the summer of 1919. . . I rose to the occasion and silenced the radicals.”

Flowers, on the other hand, remained frustrated, and angered, at the “hierarchies and exclusions of the colonial order during the 1910s”

A few days after the riot, on the 26th of July, W. H. Hoar, a colonial official, claimed he overheard a woman complaining: “the black men have no pluck. The women have to be behind them all the time or else they will do nothing.” That woman was Annie Flowers.

The book Quilter: A Weaving of the Women’s Movement in Belize notes that Flowers “wanted to live in a Belize that was independent and equal. She raged against the colonial masters for holding Belizeans in bondage, and she rallied against the black men around her who allowed themselves to be walked over.”