Amandala’s publisher, Evan X Hyde, has described Cornelius Patrick “Pat” Cacho, 87, as “brilliant.” Born in Dangriga on October 2, 1926, Cacho rose from a lowly job as messenger at the Treasury Department to becoming Belize’s Economic Secretary under the George Price administration of the 60s. Cacho had a lot to offer Belize and the government of the day, but he felt that his intellectual talent was being wasted, so he resigned and moved on to an assignment at the University of the West Indies and later to the World Bank, where he served just over two decades, mostly on missions to Africa.

Mr. Cacho, who is home for a few weeks to help build capacity for science education in Belize, sat with Amandala today for an extensive interview on his life’s journey and his enduring dreams for a better Belize.

He told us that in his time there weren’t many Garinagu in the ranks of the public service. In fact, he was the most prominent, and his family never hid the fact that they are Garifuna.

“At the Treasury, people regarded Cacho as a boy –‘he is cleaning the desk but he wants to go somewhere…’” he recollected.

His parents, Lorenzo and Ignacia Cacho, migrated to Belize City when he was only 6 years old. There were those from his hometown who felt that Lorenzo Cacho was abandoning his culture, but there was no high school yet in Dangriga, and the father was adamant that his only child would get a secondary school education. Cacho told us that most youth then only went up to Standard Six before entering the workforce.

“By bringing me up here [to Belize City], they gave me that chance,” he said.

Cacho’s father had a tumultuous childhood. His grandfather had abandoned his grandmother, and because she could not afford to raise them, she loaned Lorenzo Cacho to a Methodist missionary. He, too, became a Methodist and so did his son, Pat Cacho.

The younger Cacho was pushed by Floss Cassasola, one of his mentors, to sit the scholarship exam a year early. He was awarded a scholarship to study at St. Michael’s College. He told us that his grades were so outstanding that he was exempt from matriculation requirements for further study in England.

Even with his high school education, Cacho could only get a job as a messenger. Needless to say, his father was disappointed and kept pressing him to find another job.

Cacho recalls that his father had acquired an old typewriter, on which they had to practice in the mornings before school, teaching themselves from manuals. That skill he picked up at home became his ticket to a promotion about a year later, from messenger to typist at the Treasury.

However, Cacho maintained his ambition to rise up the ladder, and he began taking correspondence courses from the London School of Accountancy.

“It was difficult because communications were not the same. [Your documents] took a month to reach there and it took another month to get the results back,” he said.

Meanwhile, Cacho rose to become a junior clerk and worked his way up to becoming a third class clerk—that is, before he went off to Birmingham, England, to learn about treasury management.

His initial leave was for 1 year and Cacho told us that he decided that if it killed him, he would do whatever was necessary to get an extension for at least two years to attain his accountancy qualifications. He passed his professional exam in 1952. He had applied to the City Treasurer in Birmingham, who supported him for the two additional years.

“I just killed myself with studies and in two years, after applying myself to hard work, I completed and received [my qualifications from] the Associate Chartered Institute of Certified Accountants,” he said.

“I got carried away by my ambitions. I fell in love with economics,” he continued.

Cacho then proceeded to the London School of Economics – one of the premier schools there, where his major professor was a Nobel Economics Laureate, James Meade (1977).

He spent a total of 6 years on study leave, and returned home with his wife, Laura, and daughter, Carolyn. We noted that Cacho did not explain how his wife got into the picture. So he began to explain that before his initial departure from Belize, he married Laura Noguera, who passed away in 2007.

Days before Cacho left for London, Laura had given birth to their first child, Evan. Regrettably, that child died about a year later and Cacho said that that was the only time in his life when he honestly contemplated suicide.

Back in Belize, Laura had the support of his parents, who pooled money to send her off to England so the grieving couple could be together.

Cacho told us that there were four other children of the marriage: Carolyn Patricia, who is a nephrologist; Joyce, who holds a doctorate with specialty in agro-economics; Denise, who had the opportunity to attend school in India and who was hired to head a center for women and families in Louisville; Kentucky; and Lawrence, who is in Kenya on a mission for the U.S. State Department.

Myrtle Palacio, Secretary General of the Opposition People’s United Party, is Pat Cacho’s eldest child, and he told us that she grew up in his household.

After discussing his family with us, Cacho told us more about his professional life in Belize, and what caused him to migrate from Belize in the 60s.

He worked for the Government of Belize for 7 years. He was first appointed as Assistant Secretary for Development in the Ministry of Finance, and later appointed as the Economic Secretary in the same Ministry, under the former Premier, Hon. George Price. Cacho said that he had strong views on some development issues, but no one was listening. He went off on a fellowship to do his Master’s degree and returned to Belize.

He was concerned about the lack of proper support for small farmers and wanted to see a program that would help them enjoy bigger yields. He was also concerned about the state of education in Belize. He thought it imperative for the Government to do something about both.

Cacho told us that initially he was happy to work under Mr. Price, because he realized that Price didn’t want anything for himself – for the party, yes, Cacho added.

“I thought he was a god-send. He didn’t womanize. He did not have any woman in his life to create problems. He went to Mass every morning. He didn’t want riches: as long as he had a decent guayabera, George was all right,” he commented.

Cacho said that whereas it appeared to the outside world that he had influence on Price’s actions, he did not. He told us that he could be very frank with Price but he didn’t seem to take umbrage.

He told us that Price started to politicize the public service: “I commented on an appointment: ‘Square peg in round hole,’” he recollected.

“George said, ‘he supports the party’. I said, ‘what we want, Prime Minister, is not somebody who supports the party but somebody who is competent to get the job done.’ So we had that kind of thing going”, Cacho explained.

While C.P. Cacho was on a 7-month fellowship at the World Bank in Washington, the personnel officer offered him a job there. They told him he was “bank material,” but after consulting with his wife, Laura, who was teaching home economics at the time at Belize Technical College, the couple decided to pass on the offer.

In 1966, Cacho got enough. He said that he realized he was sacrificing a future for his children that he could build for them and the sacrifice in Belize was not worth it.

“If I could do that and help my country, fine! But I was not helping my country,” he said.

He said that it was time for him to leave and go where he could get more professional fulfillment and make money. By then, he and his wife had three children. Lawrence was born while he was working for UWI in Trinidad.

“When I got fed-up [with the Government of Belize], I decided I would try to get into academia through the backdoor, so I ended up at UWI,” he went on.

He said that Alistair McIntyre, his dear friend, was at UWI and they thought they would collaborate to do some research and writing. He was hired as the bursar, which means that he ran the finances. He also designed and taught a course on international economics for the graduate diploma in international relations.

Cacho said that when it appeared that UWI was possibly breaking up, he called the World Bank to say that he was ready to join them. In two weeks, he and his family flew to Washington. In another two weeks, he was on the job.

“When I joined, I said, you know, I am a black man and I would like to help black places. Although I did have missions to Peru and one or two other places,” he told us.

Cacho has served as the World Bank’s Chief of Mission in Somalia, one of 10 African countries where he worked during his tenure at the bank. He also worked for the World Bank in Nepal, Bangladesh and Peru.

“I had a very satisfying career with the World Bank. I was the Chief of Mission in Somalia, and I have to tell you what that meant. It meant I had a car with a flag and a driver in uniform, although I hardly used that – it was only when I went on official things…” he recalled.

Mr. Cacho retired from the World Bank at the age of 62, the earliest retirement age. He said he got fed up with the World Bank because he did not think it was true to what it said it was about.

“By then, my children had gone through college, and my wife and I did not need a lot of money to live on,” he told us.

Now retired, one of his aims is community service and giving back to his home country.

Ten years ago, Cacho donated funds to spearhead the establishment of the Ignacia Cacho Library in Dangriga in memory of his mother.

This time he wants to invest in high school labs. He told us that he is prepared to partner with the Government to strengthen some labs that may need strengthening and to establish labs that may need to be established. They have not yet agreed on how many labs and how much money.

Mr. Cacho hopes that within the next month, he would get a note from the Ministry of Education telling him which schools would be supported.

“I just want to do something for my country. The only stipulation I have made, kind of, is that one of the labs should be in Dangriga,” Cacho told us.

He stresses the importance of education, saying it is “absolutely essential, absolutely key…”

He is also concerned about the crime situation in Belize: “I see a lot of things that I don’t like. I’ll touch on one thing: we became the third most murderous country in the world,” he said.

Cacho said that the persons involved in crime weren’t born murderers or criminals, and there is the need to “find out in some detail” what the problem is and why people behave the way they do, then “raise heaven and hell to try to improve their conditions.”

Mr. Pat Cacho has been enjoying retirement, and he is planning on writing his memoirs: “I’ve been thinking about memoirs and when I came here 6 years ago, it was really to collect materials. I spent most of the time at the archives, but they don’t have too much….

“There is a lot that I know that isn’t generally known. For example, that I headed the subcommittee that recommended that this area is where the capital should be. Not too many people know it. George Price knew it. Henry Fairweather knew it,” he continued.

There are other things he said that are “worthy of the public’s knowledge…” He spoke of an old friend, Rafael “Falo” Fonseca, former Permanent Secretary in the Ministry and the father of Ralph Fonseca.

“Evan X has written that Falo and I had differences; that I should have had the job, because I was black I didn’t get the job. No truth. Falo Fonseca, my love, is one of two or three people who were my closest friends,” Cacho said.

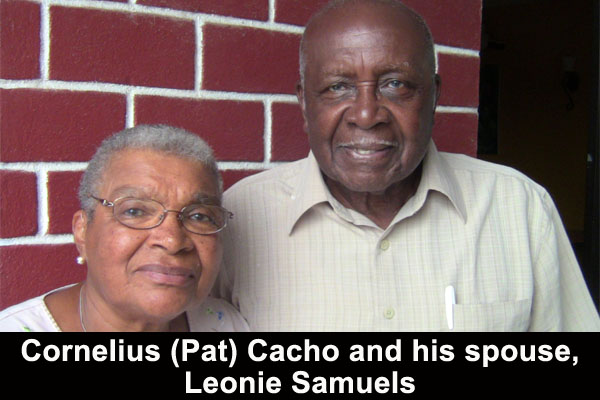

Cacho’s memoirs are for a future time. Meanwhile, he wants to complete his project with the Ministry of Education. Later this month, he returns home to Naples, where he and his current spouse, Leonie Samuels, are among the few blacks who live in a white gated community he now calls home.

Racism was rampant when he studied in England in the 60s: “They slammed doors in my face and all kinds of things. [It] woke you up…,” he recalled.

Thankfully, things are much more civil where he lives today in Naples.