You know how small Belize is. My wife’s older sister is married to Roman Catholic Bishop Dorick Wright’s maternal uncle, Joe Purcell. On a recent visit home from California, my sister-in-law visited Bishop Dorick, and afterwards told me he had asked for me.

Bishop Dorick and I were close friends in Sister Mary Francine’s Standard VI class at Holy Redeemer Boys School in 1958/59. He and I went separate ways in life. In fact, Bishop Dorick became the highest ranking prelate in the Catholic Church in Belize, while most of the Catholic faithful have considered me an enemy after I began rebelling against their school curriculum with reference to African and Mayan history. I lost most of my Catholic friends, including black ones.

Visiting Dorick recently, there was a certain poignancy for me as I turned left from North Front Street into the Holy Redeemer yard. Bishop Dorick is on the top floor of the relatively new, huge three-storey building constructed where the Standard I to Standard VI classrooms used to be. That’s in the corner of the Holy Redeemer yard which is bordered on the east by Queen Street and on the south by North Front Street.

The infant boys’ classes (before Standard I) used to be on the other side of the Holy Redeemer block, a block which was divided by a canal which ran from the Haulover Creek in the south all the way to the old Belize City Hospital/old Belize City Prison area. The “other side” of the Holy Redeemer yard, which is bordered on the west by Hyde’s Lane and on the south by the aforementioned North Front Street, was where the Holy Redeemer Girls School was located. So, as infant boys, we were on the girls’ side.

The “backyard,” where we boys played during morning recess, was in the northern area of the Holy Redeemer block. There were also two workshops in that area, and later a hostel for St. John’s College students from the Districts, and this area would be bounded on the north by New Road.

Bishop Dorick Wright is a diabetic who is fighting for his life. He has to submit himself to dialysis at the Karl Heusner Memorial Hospital (KHMH) three times a week, and each session is four hours long. One of his legs has had to be amputated at the ankle, so he has to have that treated and bandaged frequently.

I mentioned the poignancy of the visit for me which had to do with my entering that section of the yard where I had attended school for at least four years as a child more than six decades ago. I was in Standard I with Miss Louise Smith, Standard III with Sister Stephanie and Jean Rosado, Standard IV with Miss Ilna Alamina, and Standard VI with Francine. (I deliberately leave out the “Sister” part with Francine to give you a sense of how “tight” this lady and I were.) I’m not sure if I passed through Standard II. I know that Carlson Gough and I skipped Standard V to go to VI.

Bishop Wright and I have enjoyed two “sitdowns” where we remembered many of our old classmates and teachers. The chances are we have not had this type of conversation since Hurricane Hattie. We’ve met very briefly at church functions through the years, where we have exchanged pleasantries. But, to repeat, we had gone very different ways, ways one may describe as diametrically opposed ways.

In this essay, I would like to touch on the emotions I felt recently when I thought of all the sincere Catholics who knew me as a child and as a youth when I was an academic star of theirs. They would have felt a sense of betrayal after 1969, knowing that it was their teachers who had provided me with the educational foundation which enabled me to survive at a foreign university level.

The rivalry between the Christian denominations in Belize City was intense “back in the day.” Catholic, Anglican, and Methodist children competed against each other in football, radio quiz contests, and the like. Of course our respective teachers belonged to the religion in question, and so we were all brought up, in our separate schools, to believe that our religion was the best and our school was the best.

(I don’t believe the Jesuit Jerry McElroy understood how serious the rivalry was between Catholic St. John’s College and Methodist Wesley College in the streets back in 1963 when he took a baseball game between SJC and Wesley College lightly. I forgive him because he was ignorant.)

The more I thought about it while reminiscing with Bishop Wright, the more I became struck in recollection by the religious fervor and loyalty of the teachers I had known at Holy Redeemer, and I am sure a similar fervor and loyalty existed amongst the teachers in the Anglican and Methodist school systems. I don’t know how it is now, but back then our primary school teachers worked in dark, cramped, crowded classrooms where children were always unruly and often rebellious. Big, big respect to our teachers.

I thought of how my primary school teachers at Holy Redeemer must have reacted when they heard of all the trouble their former student began to give after 1969. For my primary school teachers to have felt betrayed was understandable. Personally, I knew there was a price I had to pay and I knew I had to pay it. It was impossible for my teachers to understand in 1969 that the same way they believed in the Church, the same way I believed the Church was wrong where the matter of African and Indigenous history was concerned. They have a saying that sometimes in life you have to bite the bullet. There’s nothing to do but accept the pain.

I brought up the name of a teacher to Bishop Dorick who had never taught me personally. Her name was Miss Pineda, and what was unforgettable about her was her intensity. He remembered her right away: Arcadia Pineda from Chan Pine Ridge. How about that? She is still alive, and visits the Bishop in the City every year for his November birthday.

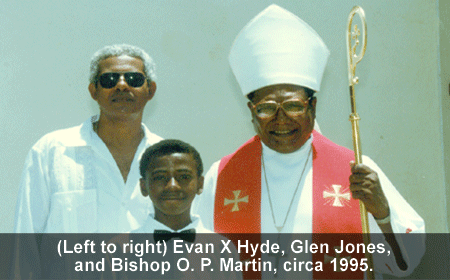

More than two decades ago, a Roman Catholic teacher, Mrs. Veronica Jones from St. Martin de Porres Primary School near to us on Partridge Street, asked me to stand godfather for her son, Glen. The Roman Catholic Bishop at the time, the late Osmond Peter Martin, accepted me as a Catholic godfather. I would say he knew I was not a believer, but he knew that I would honor my godfather’s vow to make sure Glen was raised in the Catholic faith if anything happened to his parents. At least, that is how I reasoned it out. (Today, Glen Jones is now Dr. Glen Jones, a physician who works at the KHMH.)

When I mentioned that event to Bishop Dorick, I would say, between me and you, that the look on his face suggested to me that he might not have taken the same position Bishop Martin did. I’m just saying. One of the strengths of the Church through the millennia has been its flexibility on the ground, as we can see where the symbiosis between the traditional liturgy of the Church and Garifuna religious practices are concerned.

I called Bishop Dorick this Tuesday afternoon to let him know that there would come a time when I would write about my visits with him. He was resting because of dialysis earlier in the day, so, strictly speaking, I am writing without his permission. I don’t need Bishop Dorick’s permission to write, you understand: it was a matter of courtesy, and friendship. I have a special respect and love for Dorick.

Those of you who know me well, know that my problems with the Church were not confined to African and Mayan history. I had hostile experiences with a Jesuit priest named Ronald Zinkle. Catholics have to support their own. Me, I had to do what I had to do. Such is life.