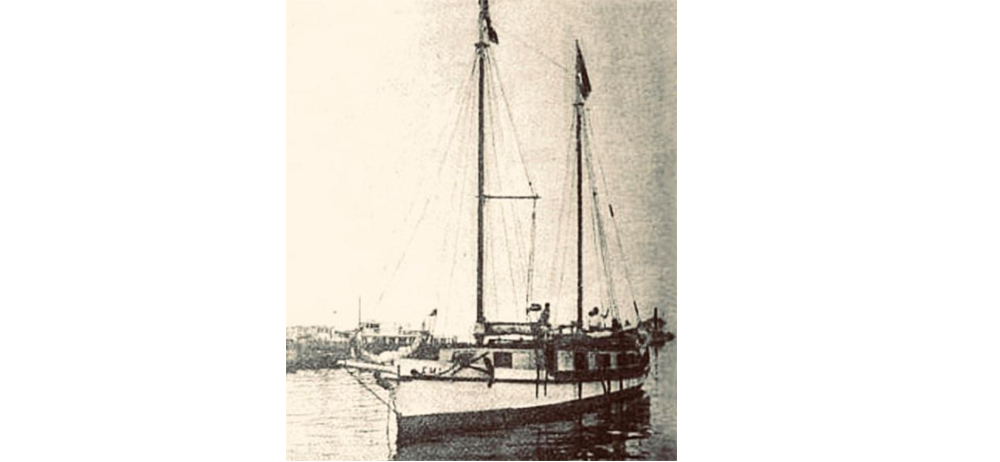

by Donia Scott

Part 5: Swept under the Carpet

The first sign that the reaction of the Colonial government to the disaster of the sinking of the E.M.L. would not be following a clear moral path appears in the side notes attached to the draft reply from the Secretary of State, the Duke of Devonshire, to the Governor of British Honduras’s dispatch to him of the 7th of May. All official letters from the Secretary of State are first drafted by one of his senior civil servants, who may add advisory notes for him in advance of the final version. The notes in this draft say that the Secretary of State’s staff was fully aware of the blame on the Governor, Sir Eyre Hutson, and of the failings of the Colonial Secretary, the Honorable Maximillian Smith. They recommended that since the reply would no doubt be published …

… it seems undesirable to add to it a slating of the Colonial Secretary, which in any case would not do much good. If anything is to be said to the Governor on this point, I would suggest that it might be done semi-officially.

The resulting official reply to the Governor expresses “sincere sympathy” with the bereaved relatives of the victims and “deep regret” to the Roman Catholic community for the loss of Bishop Hopkins. Nothing more.

Another ominous hint appeared in the Clarion only two days after the fatal sinking. Typically, the Governor of a Colony would be required to order a Commission of Enquiry when passenger ships collide within territorial waters, even in cases where there is no loss of life. However, the Editor of the Clarion writes on April 12 that despite requests for an Enquiry to be held regarding a collision at sea that had occurred only a month before between two other mailboats carrying passengers—the Afri-Kola and the Maggie B—the Governor had ruled that no such Enquiry was necessary.

In the days immediately following the tragedy of the E.M.L., the Clarion published several articles and letters urging the Governor to act responsibly this time around:

In the present catastrophe the Government cannot shirk their responsibility in this respect. Delay in holding an enquiry often defeats its object. It should be held immediately. We earnestly hope that full blame will be brought to those responsible for this sad fatality.

Given that the sinking of the E.M.L. resulted in loss of life, especially of such a well-known and much-esteemed person as Bishop Hopkins, there would be no question that a Coroner’s Enquiry would take place. Indeed, it was not within the power of the Governor to prevent it. But, of course, a Coroner’s Enquiry (also known as a Coroner’s Inquest) and an independent Commission of Enquiry are two rather different kettles of fish. The former serves only to determine cause-of-death and, where appropriate, to recommend that criminal charges be brought. The latter is a full examination of the ‘what-went-wrong’, where fault (if any) can be identified, and to recommend rectifying procedures (again, where appropriate); occasionally, they can also lead to criminal charges being brought.

On April 19, as depositions began to be taken at a Coroner’s Inquest in Corozal, the following editorial appeared in the Clarion:

We understand that a Coroner’s Inquiry is being held at Corozal as a result of the sinking of the “E.M.L.”. With this we agree as far as it goes, but there should be issued in addition by the Governor a commission appointing competent commissioners to make a full, faithful and impartial inquiry into the Cause of the sinking of the vessel and the conduct of the crew and passengers. Under the provisions of our law a coroner is empowered merely to hold an enquiry into the cause of death, what the occasion demands is the laying bare of the actions of those responsible for this unseaworthy vessel being permitted to carry passengers. It will be a public scandal if no such inquiry be held and we most earnestly and strongly urge His Excellency to lose no time in setting up such a Commission.

In the Governor’s May 7 dispatch to the Secretary of State, he reported:

An inquest has been held under Chapter 25 of the Consolidated Laws, and the report of the Coroner is now in the hands of the Attorney General. I am informed that proceedings will be taken against the Captain of the vessel at the forthcoming Criminal Sessions of the Supreme Court.

The Governor later wrote to the Secretary of State on August 15 to solicit his advice on the matter of whether he should open a Commission of Enquiry into the disaster, as he was being urged to do by the local press and by one particularly vocal member of the British Honduras Legislative Council, the Honorable A.R. Usher. He reported that the Attorney General had advised him that it was not in his power to deal with the report of an Enquiry beyond forwarding it to the Board of Trade in England. He also reported that he was not able to withdraw or cancel the certificates of the Captain and the Engineer of the E.M.L. “because those persons hold no certificates”. Furthermore, although the Captain had been criminally charged for the death of the Bishop and other passengers, the Attorney General subsequently reported that he had “entered a nolle prosequi in the case”. In other words, the Attorney General had decided that the case against the Captain should not proceed to trial for the following reasons:

That there was insufficient evidence to support a charge of manslaughter against the master of the vessel. That in so much as the accident, the result of a series of alleged omissions, took place well within the Mexican waters, the question of jurisdiction entered largely into the case. That though this latter reason was important, it was not a decisive factor in his ultimate action. That being well decided on the point that the Crown could not secure a conviction he was not prepared to involve the Colony, or the accused, in an expensive and long trial at Corozal for the sake of calling on the accused to meet a prima facie case of a flimsy nature.

The Attorney General’s view was quite astonishing, not least because two government officials, the Assistant Harbour Master and Senior Customs and Excise Officer for the Colony, Robert Masson, and the Colony’s Superintendent of Police, Herbert Lawrence, had reported in their sworn testimony at the Inquest that they took several bearings of the wreck showing it to be located within the Colony’s territory. Now, four months after the tragedy, we see the first and only mention that the wreck occurred well outside of territorial waters. We also see for the first time the tragedy referred to as “the accident”.

Returning to the matter of the possible Commission of Enquiry, the Governor further reported to the Secretary of State that both the previously-mentioned Attorney General, the Honorable Cyril Gerard Brooke Francis, who had now been made Chief Justice, and his current incumbent, the Acting Attorney General, the Honorable F.R. Dragten, K.C., had informed him that they would not be prepared to accept the position as Chairman of any Commission of Enquiry. The only remaining possibility for selection to serve as Chairman, he said, would be the Chief Justice, Mr. K.M. Sisnett, but he was away on leave up to the end of October, and in any case.

I consider it likely that Mr. Sisnett would raise objection to his appointment to serve on the Commission.

The Governor concluded his dispatch by saying that he had informed the local Legislative Council of his opinion that “a Commission of Enquiry would not be required”, and of his intention “to invite the Secretary of State’s orders in the matter”.

On September 3, the Governor received a short reply from the Secretary of State:

I agree with the Governor that a further public enquiry would not serve any useful purpose.

And there the tragedy of the wreck of the E.M.L. was laid to rest.