The piece below is a writeup in The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Winter/Spring 2013 edition. The original piece could be viewed with his picture at www.studiomuseum.org.

E.J. Hill, Jr., is an MFA candidate in New Genres at the University of California, Los Angeles, specializing in performance. Hill is interested in questions of identity, territory and alienation. Using durational and interventionist strategies, he advances counter-narratives in which marginalized bodies are free to inhabit spaces of their choosing—physical, emotional, social or political.

Can it just be a body?

Hill moved to Chicago in 2007 to study at Columbia where he initially focused on painting and drawing. After watching a collection of videos by artist Chris Burden, known for his confrontational performance style that tested the limits of the human body, Hill initiated what he refers to as his first performance: a psycho-geographical duration exercise for which he crawled, à la William Pope.L, between the town center and a so-called “bad part of town” in Evanston, a suburb on the far north side of Chicago that is home to prestigious Northwestern University. Weighted down with a backpack filled with drywall from an abandoned house, Hill intended for this—as well as a later work, This Is an Imaginary Border (2009)—to open a dialogue about the economic (and occasional racial) segregation that remains a reality in cities such as Chicago.

“I had no idea I was ‘black’ until I moved to Chicago,” says Hill “I’m a first-generation American—my family is from Belize. They moved to Los Angeles in the 1970s. When I got to Chicago, my Belizean identity was taken out of conversation, unless I brought it up.”

Hill is conscious, to the point of frustration, of how his body while performing will be viewed through the prism of race and gendered expression. “The kind of performance work I was initially acquainted with was done typically by white men,” says Hill. “I began to wonder whether other artists like [Hannah] Wilke or [Fluxus artist] Shigeko Kubota could escape their gender or cultural baggage in the reading of the work.”

Hill remains optimistic, however, that through a rigorous and diverse practice, the conversation can move beyond the personal and immediate to broader, universal ideas and relations.

Now back in Los Angeles, Hill is working closely with artist Andrea Fraser at UCLA, noted for her performance grounded in institutional critique. Hill is testing new work in drawing, video and photography to combat what he sees as “expectations” of his work.

“A friend once said, ‘We choose who we bleed for. Most people don’t deserve to see you struggle [during a performance], or sweat or cry or bleed.’ It’s a strange psychology, [for a viewer] to come to a place hoping to see or experience something

really intense,” Hill says.

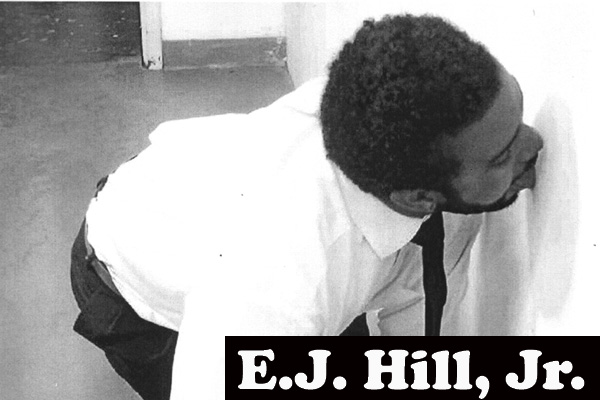

A recent performance, Drawn (2011), has Hill, dressed in a white button-down shirt and tie, licking the walls of a gallery until his tongue bled, leaving behind a faint trail of pink. When asked why he doesn’t do more performance for video in the controlled space of his studio, Hill says that while there are problems with making performance in public, he views

an audience’s presence as “silent encouragement” to “go where [his] mind didn’t think it could go”—beyond limits or inhibitions.

For Hill, performance is a complicated practice. His family has mixed emotions about his choice to be an artist. He refers to a recent suite of photographs as a “peace offering” to his family, so that he “has something to show” them about what he does.

Is performance, using the body as site and medium, more ideal for bridging the perceived divide between the “art world” and the “real world”? What about the added complexity of being an artist of color making less traditional work?

Of this, Hill remarks, “I feel a certain responsibility to my family and neighbors in Inglewood to bridge the gap. . .

The position we assume is not that of just being an artist, but an artist-educator, to express how we got to this point, and that there’s a legacy we’ve inherited as art workers.”