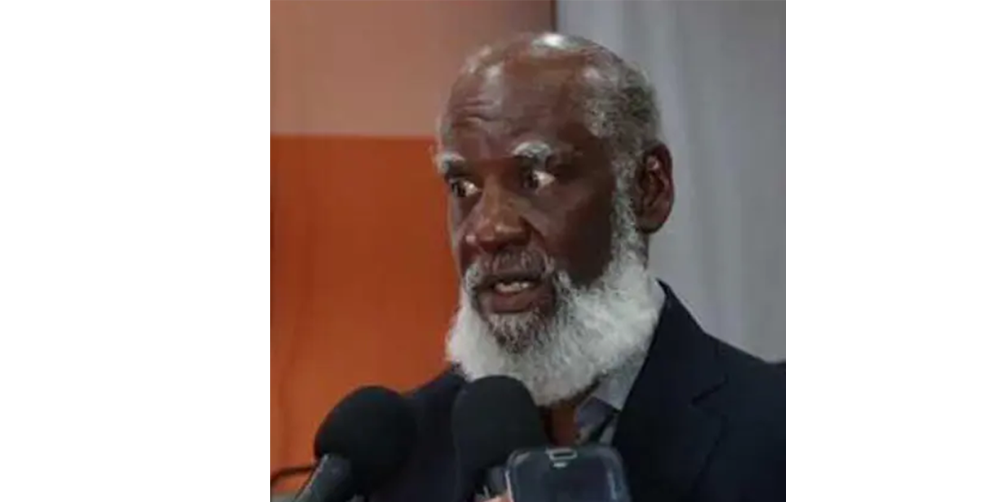

Photo: Wilfred “Sedi” Elrington

by Marco Lopez

BELIZE CITY, Thurs. Feb. 22, 202

The protracted legal battle between Senior Counsel Wilfred “Sedi” Elrington and the father/son duo of Progresso Heights LTD (PHL) has come to an end. Belize’s final appellant court, the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) handed down its judgment in the appeal lodged by Elrington, challenging the decisions of the Belize Court of Appeal and High Court. That appeal was dismissed by a panel of CCJ justices. Its written decision was released earlier this week.

This case surrounds a land dispute between the former UDP Cabinet minister, and the principals of Progresso Heights, Lawrance Schnider and Adam Schnider.

Elrington held 20% of the shares of the company, PHL. The other two directors retained the remaining 80%. However, Elrington reportedly had placed several caveats on the land owned by PHL, preventing the company from conducting any business related to the land.

The first claim brought by PHL was heard in the Belize Supreme Court. The trial judge at the time found that the caveats were unlawfully lodged by Elrington, and unlawfully accepted by the Registrar of Lands at the time.

The trial judge ordered that the caveats be removed, and no further holds on those lands be accepted by the Registrar of Lands without the permission of the court. Elrington lodged an appeal of this decision in the Court of Appeal.

The Court of Appeal noted that only one ground of the appeal challenged the primary finding of the trial judge; the other ground concerned whether the proceedings were properly brought by PHL. The appeals court held at the time that Elrington did not raise in his pleading before the trial judge, the issues of the legitimacy of the proceedings commenced by PHL, therefore the court could not consider it. This appeal was dismissed as well.

An additional appeal was lodged at the court of last resort in our judicial system, the CCJ, with several grounds of appeal against the decision of the trial judge filed.

Elrington’s legal team sought to argue once more that the trial judge was wrong to find that the elder Schnider had “actual or ostensible” authority as director and agent of PHL to sell the lands in the possession of the company, or to testify on behalf of the company.

He argued that PHL was not properly a party to the proceedings.

On the date of the hearing, however, Elrington’s legal team applied to the court to amend his notice of appeal, changing the terms “trial judge” and “High Court” to “Court of Appeal.”

The lead judgment, written by Justice Maureen Rajnauth-Lee identified two issues. The first dealt with whether permission to amend Elrington’s notice of appeal should be granted. The CCJ did not allow this application, stating that waiting until the day of the hearing of the appeal to amend the notice of appeal was unacceptable and unfair to PHL … “particularly, in the absence of any convincing grounds or reason,” the judgment stated.

The CCJ underscored that late applications to amend the notice of appeal, or any other application particularly made on the day of the hearing, were to be seriously discouraged.

The second issue dealt with whether the Court of Appeal was correct to hold that Elrington could not succeed on his appeal due to his failure to plead that PHL had commenced the proceedings without the requisite authority.

The CCJ emphasized the importance and function of pleading is to give fair and proper notice to the opposing party.

The CCJ was of the view that there was no reason to interfere with the decision of the Court of Appeal. It added that Elrington never raised the issue in his defense at the High Court.

The concurring opinion by Justice Winston Anderson highlights that although the appeal was filed as of right, it could be struck out if it was an abuse of the process or if the issue pleaded was not properly before the court.

He shared that the abuse of process is a “very high bar” to meet and requires bad faith. He was not prepared to consider that the application had reached that bar.

Touching on the importance of pleadings, Justice Anderson found that the application to amend the pleading was not to remedy a simple clerical error, but went to the structure and substance of the case and had taken PHL by surprise.

He found that six of the nine issues on appeal to the CCJ could not be raised, as they had not been properly pleaded before the High Court. The simple solution, the judgment states, would have been for Elrington to have made an application to amend the pleading at the appropriate time before the trial judge.

At the time of the trial in the Supreme Court, he failed to do this; as such, this appeal was dead in the water from the outset.

Justice Anderson pointed out that there was no right of appeal against interlocutory decisions, even in civil cases. The remaining three grounds of appeal were in essence about certain interlocutory proceedings before the trial judge, for which leave had not been sought or granted.

“As such, the appeal to the CCJ was not properly before the court,” the written judgment stated.

The CCJ dismissed this appeal. The orders of the Court of Appeal were affirmed, and Elrington was directed to pay PHL’s cost of this appeal.

The case was heard at the CCJ by the president, Hon. Adrian Saunders, Justice Anderson, Justice Rajnauth-Lee, Justice Burgess, and Justice Jamadar.

Elrington represented himself, with the help of Paulette Elrington-Cyrille, and Ms. Prescilla Banner appeared for Progesso Heights Limited.