by Donia Scott

Part 2 — A Perfect Storm

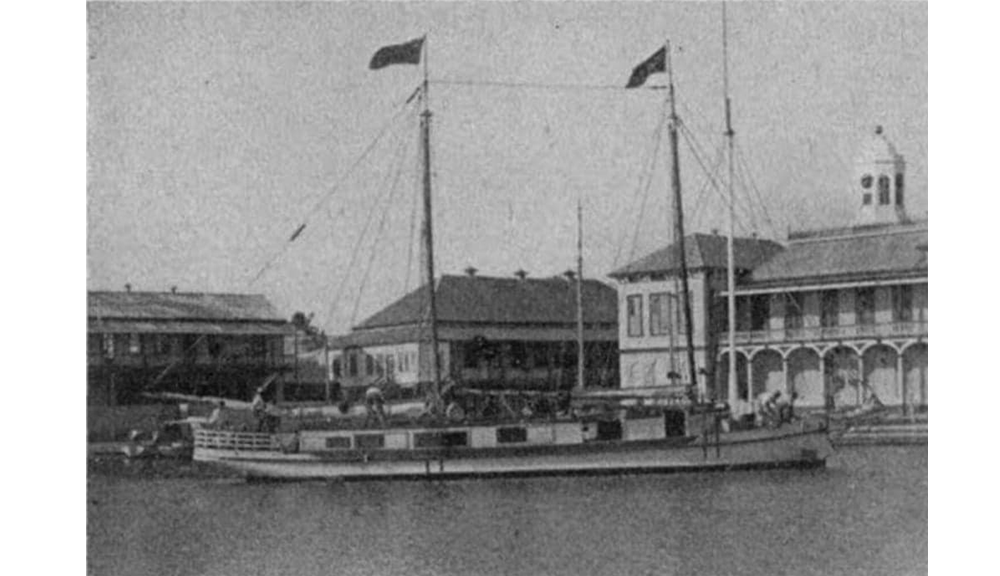

In the mid-afternoon of Monday, the 9th of April 1923, the mailboat E.M.L. set sail from the harbour of Belize, the capital of the British colony in Central America, then known as British Honduras, bound for the northern towns and postal stations. Grossly overloaded with both passengers and cargo, and leaking dangerously, the E.M.L. never reached her destination.

Steaming north towards Mexico, with virgin swampland to portside and the world’s second-largest barrier reef to starboard, the E.M.L. should have reached the Rocky Point lighthouse in about ten hours and arrive in Corozal an hour later. There it would unload some of its mail, cargo and passengers before heading south to enter the New River, stopping at the townships of Progresso and San Estevan before reaching its final destination of Orange Walk, the colony’s second-largest town.

This was, at the time, the only feasible mode of transport from Belize to the northern townships. There were no roads, and an overland route would have involved a slow and arduous horseback journey through many miles of mangrove swamps, bush, and long waits to be ferried across rivers.

That the overnight trip on the E.M.L. was the better choice of travel was little cause for comfort for its passengers. It was hardly a closely guarded secret throughout the colony that the ship was shockingly unfit to carry passengers. For several years the authorities of the northern townships had warned the government of the colony that:

She is neither fit nor safe for the carriage of passengers, no one from here who can help it, ever travels on her. Many a time the local Customs Officer has had occasion to go down to the wharf to prevent the overloading of this vessel.

Only two months earlier, Maximilian Smith (the Colonial Secretary) and Gerald Smith (Colonial Postmaster), known colloquially as “the Two Smiths”, had submitted a damning report to the Governor on the suitability of the E.M.L. for passenger travel.

On the upper deck are five berths with two beds each and two extra beds in the Saloon. The cabins are very cramped, allowing little room for a stout person to move without going sideways. Space for luggage is so limited that a trunk or even a portmanteau cannot be opened except when placed on the bunks. The beds are of board with mattresses of palmetto leaves or coarse straw. On the first deck forward, the accommodation for ladies comprises eight beds in a common apartment with beds no more comfortable than upstairs.

Accommodation for deck passengers is very limited or poor.

The closet arrangements are forbidding and little short of shocking; one being situated forward of and adjoining the kitchen.

We unhesitatingly express the opinion that there is the minimum of comfort and the maximum of dirt.

A “Coastal and River Trade Passenger Vessels Ordinance” had been scheduled to come into operation on the 1st of January of that year, requiring all vessels to be certified by the Harbour Board as to the maximum number of passengers, the minimum number of crew, deck lines, lifebelts and lifeboats according to tonnage. Power of inspection of the vessels would be delegated to members of the Harbour Board, justices of the peace, customs officers and members of the police force, and substantial penalties were prescribed for breaches. But no proclamation had been issued to bring the law into force, because of an oversight on the part of the Governor before going on extended leave. In his absence, the Harbour Master was instructed not to enforce the part of the regulations affecting the safety of passengers, as there were concerns that the new terms would delay the movement of labourers and hinder trade. The Regulations were eventually adopted on April 9th, but the E.M.L. had already cleared the mouth of the Belize Harbour on its northern journey.

Most, if not all, passengers would have no doubt known that for the past several weeks, the vessel had been in dry-dock undergoing repairs and thus was not available for passenger travel to the northern towns. Meanwhile, the route was being plied by the owner’s smaller boat, the M.C., which could only transport mail and a small amount of cargo.

But very few, if any, of them would have been aware that in the hours leading up to their departure, the vessel had been leaking and that efforts to locate the leak and pump the boat completely dry had been unsuccessful.

Some may have noticed that of the two lifeboats customarily attached to the E.M.L., only the 4-man craft was in place; it was later learned from the owner that the larger lifeboat capable of holding 14 people had been left behind for repairs.

They certainly wouldn’t have known there were not nearly enough lifebelts on board. The steward, whose duty was to check on the lifebelts, was drunk and had, at the very last moment, been replaced by a new steward, unaware that most of the lifebelts had been loaned to the M.C. and not returned.

Nor would they have known that the captain was also new. This was his first trip in charge of the E.M.L., and neither he nor the engineer was licensed.

But it would have been patently evident to all on board that the vessel was dangerously overloaded.

There is disagreement on the number of people that could be comfortably and safely carried on the vessel. According to the owner, she was capable of carrying 40 passengers. This is at odds with the “Two Smiths” report that the E.M.L. could barely carry 20 passengers and nine crew and this with shocking disregard for comfort and safety.

But on that April afternoon, there were 60 passengers and ten crew on board. Fourteen women and children, along with their luggage and trunks, were assigned to the 8-person ladies’ cabin, where the purser had also stashed all the mailbags under the bunks, along with several cartons of onions. Occupying the small galley kitchen was a family of 14: three sisters and their 11 children aged between 6 months and ten years old. The remaining 32 passengers were crowded in the corridors, the saloon, and on deck.

The “Two Smiths” report states that the vessel’s owner claimed she had 20 to 25 tons of cargo space. There is no disclosure of how much cargo was on board that afternoon, but on the evidence of those who saw her before she left, she was loaded beyond the limit of safety. A stevedore who testified at the later Inquest reported:

There were more passengers on board than I have ever seen on any trip. The only walking room was between the pilot room and the end of the cabins and a small space leading to the kitchen. All the other space was taken up with cargo.

At this point, the reader will no doubt be wondering what would possibly lead adult passengers to set off willingly on this vessel!

Presumably, many of the passengers would have been waiting for the E.M.L. to resume passenger traffic after several weeks in dry-dock.

Curiously, the husbands of two of the ‘society’ women on board, Manuela Carbajal and Alice Marchand, were presumably aware of the risks involved. Mr. Manuel Carbajal was, in fact, the ship’s owner and had for the previous two days been giving instructions to the crew to pump out the water that was entering the hold. Mr. Lucio Marchand was a government customs official stationed at the Belize harbour and should have known the vessel was unsafe.

The Carbajals owned not only the E.M.L. and the M.C. but one of the town’s largest grocery stores, located on the corner of West Canal Street and Water Lane. The city of Belize sits below sea level, surrounded by sea on one side and swamps on the other three, and so not conducive to the growing of fruits or vegetables. Each week, Mrs. Carbajal would make the voyage up north on the E.M.L. to San Estevan to purchase a full stock of fresh provisions for their store. Since that would not have been possible in the weeks while the vessel was being repaired, the couple no doubt would have been anxious to replenish their store. They would also be keen to make up for the loss of income from passengers. “Ker-ching, ker-ching”, as the expression goes.

The Marchands were a prominent Orange Walk family known for their devotion to Catholicism. The patriarch, Joe Marchand (Alice’s father-in-law) had many years before emigrated to the colony from Jamaica with the Jesuits to establish one of the first Catholic schools in the southern district of El Cayo. The disproportionally large marble memorial cross in front of the Inmaculada Catholic Church in Orange Walk commemorates his role in the colony’s Catholic community. That the much-revered Catholic Bishop, the Right Reverend Frederick Hopkins, and three of his missionary nuns were aboard the E.M.L. that afternoon perhaps quieted any fears Alice and her husband might have entertained about the trip.

Other passengers might also have been reassured by the fact that the owner’s wife was on board, along with three nuns and a revered bishop himself.

None of them could have known that the E.M.L. was doomed. Twelve hours into the journey, she capsized off Sarteneja in the Bay of Corozal within the space of about 10 minutes, taking with her 18 souls.

Except for the Bishop, all those who drowned that night were women and children. Thirteen children. Of the children, the youngest were Alice Marchand’s 9-month-old daughter, Alva, and a pair of 6-month-old twin boys, Roy and Llewelyn, from the Wood family of fourteen that had been forced to crowd into the tiny galley kitchen next to the stench of the water closet.

The body of baby Alva was never recovered, and all but two members of the Wood family group were lost at sea that night.

Part 3 next week.